Rebel music: celebrating the UK’s inclusive soundsystems

Against a backdrop of the ongoing policing of black music, Yewande Adeniran speaks to the people behind UK soundsystems and finds a rich culture of resistance, acceptance and celebration.

Yewande Adeniran

30 Aug 2020

It’s no secret that there are tensions between the state and black music. Be it grime, rap, drill, the hostile legacy of Form 696, the demonisation of black expression in the present day remains undeniably clear. Unfortunately, this is nothing new.

Every year during the August bank holiday, Notting Hill Carnival celebrates black British cultures and heritages in all their glory – or at least tries to. The criminalisation of blackness within this context is hidden under a thin veil of “ensuring that the general public is safe”. With over 1 million attendees and a lower crime rate than that of Glastonbury (which is smaller in size), it’s hard to ignore the racialisation that is rife in such claims.

Against this backdrop, Notting Hill Carnival remains a space for celebration, but also one of resistance. Occupying space, asserting yourself and bringing people together in a positive way speaks directly to this history, especially when it comes to the ongoing culture of soundsystems.

“Occupying space, asserting yourself and bringing people together in a positive way speaks directly to Notting Hill’s history of resistance, especially when it comes to the ongoing culture of soundsystems”

In spite of growing commercialisation, carnival continues to push a DIY music ethos – soundsystems, born out of Jamaican culture brought to the UK in the 1950s, are transportable collectives who bring their own equipment to the party, the club or, in the case of carnival, the road, often building their own rigs on which to balance the speakers, amps and other equipment. Their existence serves to inspire the next generation to create their own, providing a space where young black people can learn about their history.

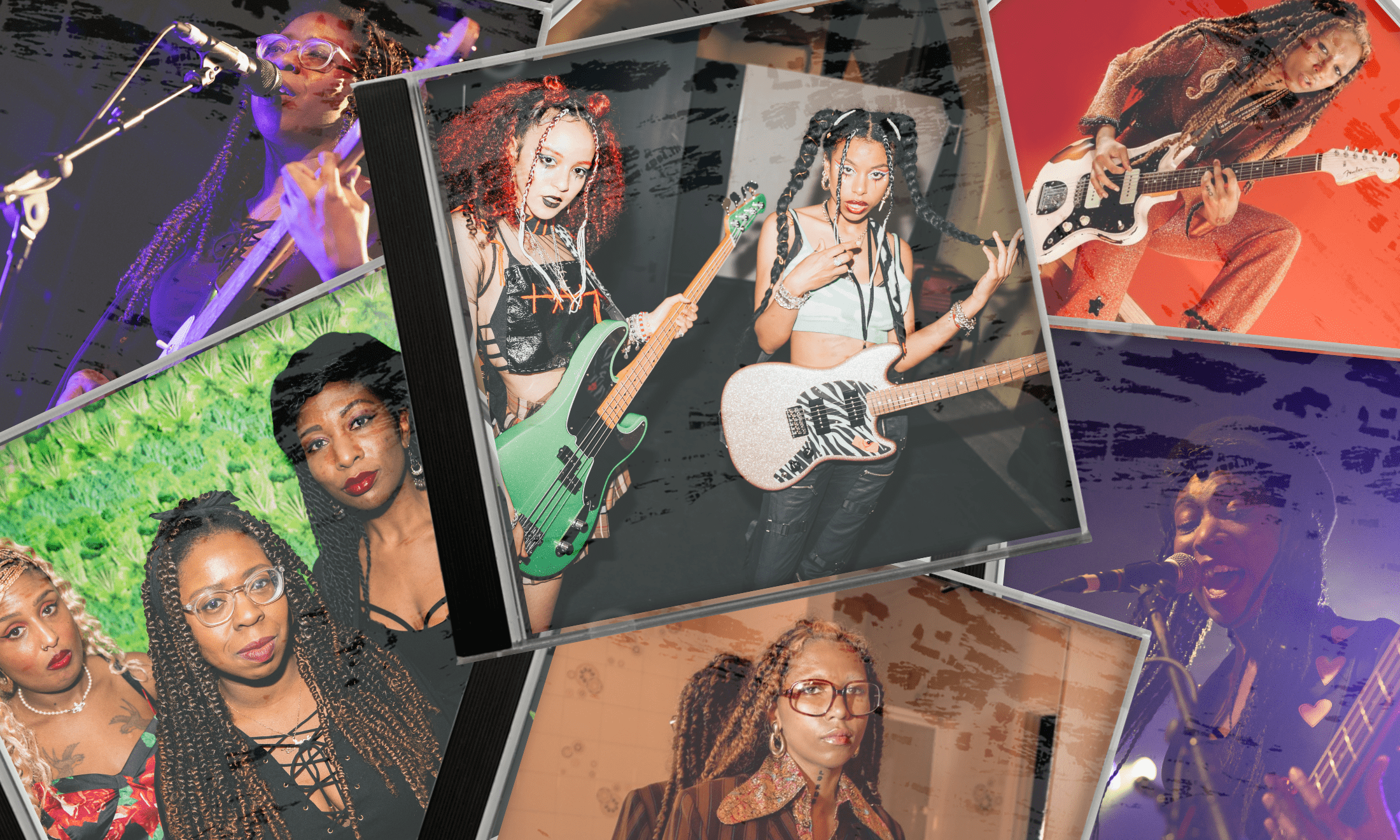

Though often perceived as hypermasculine, soundsystems in the UK now regularly welcome women and other marginalised groups. More often than not, this is a world in which people who are pushed outside of the mainstream cultural narrative can exist freely.

A key figure in the UK’s soundsystem culture is Lady Banton. Real name Marilyn Dennis, she was the first person to set up an all-womxn soundsystem at Notting Hill. An impressive selector drawing from dancehall, reggae and roots, Marilyn is currently a part of a collective she founded called Seduction City, having been part of the deeply respected Mellotone System for about 20 years.

“When playing music, there is always a message: playing old and new artists provides a message to people about resistance”

– Lady Banton

“My battle at the moment is to challenge why the authorities are trying to shut down live music and even recorded music in clubs in London – especially reggae,” Marilyn tells me. “When playing music, there is always a message: playing old and new artists provides a message to people about resistance.” She also believes it’s important to “play meaningful, conscious music, keep away from slackness and keep with the oral history of Caribbean music”.

Of course, although black music is heavily policed in London, it’s still in the capital where the culture has thrived most abundantly. However, we often find similar spaces of resistance in what might seem the most unlikely of places. At the mere mention of Cambridge, for example, elitism, pompous students and 13th-century ivory towers might spring to mind. But Cambridge’s wealth is directly linked to the slave trade and exploitation throughout the British Empire, and so it should be no surprise that an underground movement exists – spearheaded by the individuals whose places of heritage provided the financial backdrop for the places they’re now excluded from.

For Trishna Shah – known as Trishna-I on the soundsystem circuit – her time at Cambridge pub The Man on The Moon, where regular nights with collective Revelation 2000 (now Apex HiFi Soundsystem) took place, would prove to be formative. “My boyfriend at the time, Jimi Steppa, was part of Revelation, as were some friends, and they all welcomed me,” she tells me. “Some of the guys used to run Freedom Street soundsystem back in the 1980s in Cambridge, doing local blues dances. They encouraged me to get on the mic and play tunes; there weren’t many women involved but the guys always built us up and still do – it has always been a real family vibe.”

Moving beyond focusing on individual differences towards building a community is at the core of Trishna’s involvement. Establishing connections between the cities of Cambridge, Norwich (where she attended art school) and London has deepened her appreciation for those in the community who’ve paved the way.

For non-black people, an understanding and respect of reggae and dub beyond its sound, a knowledge of its history and politics, is paramount to authenticity. Trishna-I continues: “I feel that as a non-black woman on the roots-reggae scene, I should be aware of my place and ensure that whatever I’m doing, I am doing it with respect to the history of it as a movement born out of the black liberation struggle and also to the legacy of Rastafari.”

“There are roots tunes about poverty, fighting down the system, educating the children, looking after your mother… there is a tune for every moment and situation in life”

– Trishna-I

The politics of the culture is not just about taking up space and community, either – lyrically, these scenes can offer harrowing insight. Trishna explains, “There are roots tunes about poverty, fighting down the system, educating the children, looking after your mother… there is a tune for every moment and situation in life.”

Of course, dancing on the road, odds are you’re not fully taking in these lyrics – but there’s something about the freedom of these spaces that is powerful in itself. Dance music is currently at a tipping point; with more and more womxn, non-binary and LGBTQI+ individuals reclaiming their space and affirming their various identities, we’re on the verge of social change within the scene.

As part of Black Obsidian Sound System (B.O.S.S.), Evan Ifekoya’s work speaks to this social shift. Established in 2018, the aim of London-based B.O.S.S is to provide a safe space for QTIPOC, as well as making the soundsystem they’ve built available to others in the community to help connect and amplify voices that have too often been pushed aside.

“From a young age, I went clubbing, and it was in those spaces that I found a sense of belonging,” Evan says. “There is something about being next to the sub in a club – for me it feels like home and it always has done.”

A unifying ideal across soundsystems is the desire to improve the lives of those around them. Discussing their priorities and general outlook, Evan touches upon the idea of coexisting and the effective ways to do so. “I often think, ‘What is it that my community needs and what are we lacking?’ Something I’ve always noticed is that as queer black people, a lot of the organising happens in these compromised spaces.”

“I often think, ‘What is it that my community needs and what are we lacking?’ Something I’ve always noticed is that as queer black people, a lot of the organising happens in these compromised spaces”

– Evan Ifekoya (Black Obsidian Sound System)

Consolidating their work in community organising, Evan has dedicated time to learning more about the histories of QTIPOC in the UK; as we once again enter uncertain political times, looking for answers in the past might give us the guidance we need to continue to overcome. “I researched into queer and non-binary black [people] and people of colour in London during the ’80s and ’90s, and how these folks were coming together to be social and have joy despite what was going on politically,” they tell me. “Around 2016 I was very interested in the relationship between social space and politics. I was doing a lot of archive research locally, looking into the Camden Lesbian Centre and Black Lesbian Group and at the Glasgow Women’s Library. I still felt there was a lack, so I reached out to the local community through extended networks.”

Removing the distance between recent history and our present day is incredibly important. Most of our experiences, especially those of a traumatic nature, have a correlation to – or are a result of – a past event. Oppression is the end result of marginalisation. By giving a voice to those who fought in similar capacities to us, we begin to understand how to equip ourselves with the tools to survive. Evan speaks fondly of past soundsystems that ignited the decision for this form of resistance to become their daily practice. “Systematic is a soundsystem led by queer black women. I love the idea of that.”

“Art that can be understood and consumed publicly by those in the local community will always have revolutionary potential, not least when, as with soundsystems, it’s available to others in that space”

Art that can be understood and consumed publicly by those in the local community will always have revolutionary potential, not least when, as with soundsystems, it’s available to others in that space. “The soundsystem I built would become a public resource, which is different from what usually happens when art goes round in a circuit,” Evan says. “I like the idea of bringing something into existence that can really do the work it is supposed to do.”

The idea of hope and harmony is synonymous with the celebratory community of soundsystem culture: bringing people together who may not have been previously included, queer people of colour especially, to be accepted for who they are in a world that has been built to marginalise them.

“It really is all love,” Evan says. “The idea that it will bring people together. A way to work through the pain and struggle. I just wanna feel and hear more of that.”

Taken from gal-dem’s print issue UN/REST, on sale now