The dark and dirty legacy of racism at Oxford University

From students making jokes about the death of George Floyd to an incident where a blind Black student was violently dragged out of student's union, issues at the university go beyond Cecil Rhodes.

Nimo Omer

14 Nov 2020

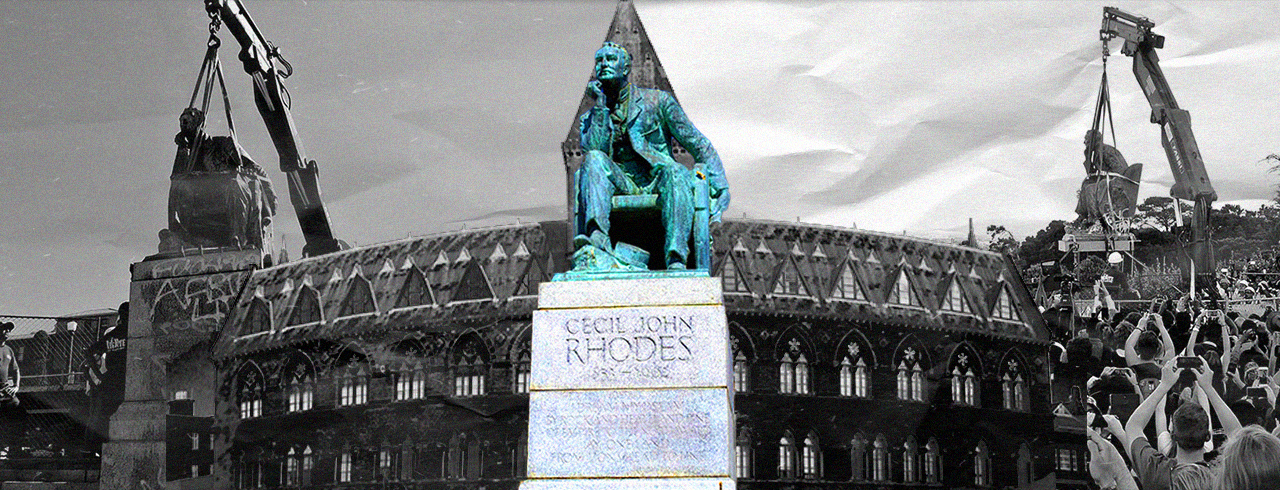

It has been over five years since Chumani Maxwele, a student of the University of Cape Town (UCT), travelled over 14 miles to Khayelitsha to collect a bucket of faeces that he brought to his campus. He walked across the university grounds towards Rugby Road, where a bronze statue of colonialist Cecil John Rhodes stood tall.

“Where are our heroes and ancestors?” Chumani asked loudly, before he began propelling excrement at the statue. In this act of protest Chumani made history. His dissidence has since become known as the trigger for an international movement that has, for the last five years, been calling for the decolonisation of higher education.

The echoes of Rhodes Must Fall was heard in universities across the world, however, it was felt most profoundly by students at the University of Oxford. Within two months, Rhodes Must Fall found its way to Oxford and students were organising, demanding that the statue of Cecil Rhodes be removed from Oriel College.

In recent years Oxford University has tried its best to shed its reputation as a former training ground for colonisers and imperialists. With all of its attempts to present a multicultural diverse institution to the outside world, the university still seems to find itself embroiled in scandal after scandal. It is easy to dismiss the issues that emanate from Oxford; it is a stuffy, archaic institution that by anybody’s definition is set in its ways. But as the university continues to exist as an entity that compounds and exacerbates racial inequality we have to closely and rigorously examine its role in society.

Whether it’s students dressing up in KKK Halloween costumes, the university itself falsely accusing a Black alumnus of being an “intruder”, the union inviting Katie Hopkins as a speaker or the prevention of the first black disabled African scholar from beginning their studies, Oxford seems to be unable to move past its racist legacy. It was only last November when Ebenezer Azamati, a blind Black student, was violently dragged out of the Oxford Union by security guards for daring to sit in a reserved seat.

While these stories created controversy and temporary embarrassment for the university, as the years have gone by, headlines have fallen into the ether, never to be mentioned again. The truth is people expect the offspring of the overwhelmingly rich, powerful, and white to be, at best, completely incognizant of their privilege and, at worst, overtly racist. And so justice is rarely ever seen. The student who dressed as a Klan member continued with his degree, graduating last summer; the incident barely a blip in his undergraduate experience.

***

Melanie Onovo, an undergraduate at Oxford’s Christ Church college has had enough of her college’s apathy and has been trying to hold her peers accountable for their actions. But she has been met with continued silence and indifference.

In the days following the murder of George Floyd, America was set alight. Protests were taking place not just in the US but across the world, with thousands of people standing in solidarity with Black people who have faced police violence. In response to what was happening around her, Melanie called an emergency committee meeting to figure out a way to donate money to the Minnesota freedom fund and associated charities. For the sake of efficiency, it was decided that the meeting would also be hustings for committee positions at Christ Church.

During the meeting a student, who decided to withdraw her candidacy, was reported to have said: “The US is facing two very important crises at the moment – the curious incident of George Floyd, and the event of flour shortage.

“I would like to put forward the motion that these incidents are not two, but rather one. Flour shortage leads to rioting, which leads to death, which leads to racism. And racism leads to death, leads to rioting, and that leads to flour shortage.”

No slurs were said, no racial epithets uttered, but these two short sentences encapsulate the flippancy and carelessness with which highly sensitive issues like race are treated at Oxford. The comparison of George Floyd’s murder with flour shortages is not just bizarre and in poor taste, it is indicative of a wider contempt and dismissiveness of the severity of racial violence.

“The comparison of George Floyd’s murder with flour shortages is not just bizarre and in poor taste, it is indicative of a wider contempt of the severity of racial violence”

Melanie was horrified and confused. She looked around her screen to see if anyone else was mirroring her disbelief but the meeting continued as if nothing had happened. “No one said anything. I tried to call it out but I was actually muted by the chair of the meeting,” she says. Melanie reported the incident to her college, following their own procedural guidelines, but she heard nothing. The same students involved in this incident, less than a month later, were then found to have defaced an image of George Floyd at a lockdown party.

It was only once Melanie decided to make the issue public, posting her experiences on Twitter, that her college conceded, writing in a statement that they condemned “the deeply offensive remarks that were made during the recent JCR Hustings, which appeared to make light of the appalling death of George Floyd in Minneapolis”. What she hadn’t anticipated was the hostile reaction from her peers.

“I received a torrent of abuse online and was racially harassed by students at Oxford University because I dared to call out this racism,” Melanie says. “My mental health deteriorated significantly because I spent eight days without sleep fighting racists online. I was hospitalised, and diagnosed with a chronic panic disorder. And now I’m taking medication for my illness caused by this situation.”

This incident, whilst small, exemplifies the multifaceted ways in which “elite” institutions like Oxford University have fostered environments that are entirely detrimental to progress and change. There is an unspoken rule at Oxford that people of colour have to suffer silently or pay a steep price for speaking out Perhaps because the space that they worked so hard to earn has never really been considered theirs to begin with. Rather it is viewed, by both their white peers and the institution more broadly, as a gift that they should be grateful for. A gift that is conditional on their silence and their capitulation to an institution that is unable to make room for them in any tangible way.

***

These incidents, if you can call them that, are not happening in a vacuum. The University of Oxford has long been an institution that has both benefited from and (re)produced colonial violence whether it is directly through large endowments given by slave holders or the memorialisation of violent imperialists like Cecil Rhodes, Chistopher Codrington, Benjamin Jowett and Augustus Pitt Rivers.

The university, for the most part, opts to turn away from this history, decrying it as mistakes from times past and viewing its complicity in the expansion and preservation of racism, colonialism and empire as little else than an unfortunate blunder that the institution has since moved away from. Now it claims to be a champion of diversity and inclusion.

Although the sincerity of these claims is often questioned – it’s not even been two years since Oxford rejected Stormzy’s offer to fund two scholarships for Black British students, which would’ve included maintenance grants – an invaluable opportunity, at Oxford in particular, as students are discouraged from taking up part-time jobs.

“It’s not even been two years since Oxford rejected Stormzy’s offer to fund scholarships for Black British students”

But Oxford is not just a university, it is not just an institution, it is a space where distinction, elitism and power are codified as inherently white. As scholars Rubén Gaztambide-Fernández and Leila Angod have aptly written, the people in these spaces become embodiments of social difference. Becoming “elite” requires assimilating into and approximating whiteness and, conversely, it means suffering if you don’t. This is perhaps exemplified in a photo that has recently been circulating on social media, of a group of Black students currently at Oxford who have recreated the infamous photo of the Bullingdon Club that featured David Cameron and Boris Johnson.

***

Nikhil Venkatesh, 25, graduated from Corpus Christi in 2016. He was BME officer at the Student Union in 2015 and was also involved in the first round of Rhodes Must Fall activism. “Once it’s pointed out to you, you notice the connections the University of Oxford has with the British empire everywhere,” he says, describing the omnipresence of Oxford’s colonial history. Nikhil stresses that it wasn’t just about Rhodes. “The university was used by the British Government to train civil servants to go and run India. These sorts of things. Once you note them, you see them everywhere and they’re so present.”

Oxford has a long, well-documented history of educating and training hundreds of men who would become central to maintaining and running the British empire. Balliol alone is known to have taught 345 men who became Colonial Administrators in India in the years between 1853-1947. This is directly contrasted with the blinkered, partial and exclusionary retelling of history that takes place at the university. In 2017 the university’s McDonald Centre proposed a five-year interdisciplinary project titled “Ethics and Empire”, that, in its own words sought to “to develop a nuanced and historically intelligent Christian ethic of empire”.

Although there was significant pushback inside Oxford itself, with over 50 fellows and researchers signing an open letter that stated their opposition, the university still gave resources to a project that sanitises the violence and barbarity of the British imperial project without holistically looking into its own complicity with said violence.

And whilst the university funds a project which does little else than expose Oxford’s inability to face its colonial history, Myra, a Masters graduate from St Anthony’s College, came into her South Asian Studies course to find that there was not a single Pakistani scholar to supervise her thesis. “They brought three Pakistanis into this programme to study Pakistan but they didn’t have Pakistani scholars”. While others were “handheld” and “had complete support” with their theses and were supervised by people who were experts in their fields, she spent a lot of time struggling to find someone to supervise and support her work.

The lack of diversity that is so commonplace in Oxfords curricula, is accompanied by a student body that similarly lacks racial diversity. In 2015 nearly one in three Oxford colleges failed to admit a single Black student. Oriel College offered only one Black student a place between 2010-2016. And between 2017-2019, 26 colleges, out of 30, admitted fewer than 10 Black students.

These stats are often obscured by the university touting its improving record with “BAME” admissions. So while things have seemingly been improving, with Oxford’s admission of BAME students increasing from 18.3% to 22.1% in 2019, they simultaneously omit the fact that in the last three years 12 Oxford colleges offered five or fewer places to Black students. Nikhil points to how discouraging it can be as a student of colour to be one of a scarce few, taught almost exclusively by white professors. “The higher up you get, the whiter it gets. And that obviously has all sorts of social and psychological implications and impacts how you experience the university.”

Oxford employs five Black professors, in comparison to 795 white professors; meaning that 0.6% of senior academic staff at Oxford are Black. Nikhil says that “both the fact that there’s very few Black and minority ethnic students there and the fact that it has this imperial history, come together to sort of constantly remind you that this place wasn’t built for people like you.”

“The reality is I paid for an education where I was sitting in class with a racist who literally would obliterate me from the face of the earth if he could”

This intensely white, elitist environment, that has been cultivated for centuries to exclude marginalised communities, has created an unbearably oppressive environment for Black and brown students. Myra had to endure the rantings of an extreme right-wing, Islamophobic student in her lectures. “The reality is I paid for an education where I was sitting in class with a racist who literally would obliterate me from the face of the earth if he could,” she says. “I’m paying for my own trauma to be honest.”

Myra’s experience, whilst incredibly distressing, is not unique at Oxford. Mirza Sameer Baig Chughtai, 20, attends Trinity College and is about to begin his third year in Law. And while he says that he has not been on the receiving end of an overt racist attack, he has still felt the culture of racism at Oxford. He recounts a committee meeting at the Oxford Union in which he heard a person, who was then running for President of the Union, say that “Palestine does not exist”. Sameer also heard another person laugh and follow up with “yeah he does not view Palestinians as humans”.

In June disenchanted Black students from Oxford came forward to say that they would no longer be willing to help with recruiting more students of colour. Mirza Sameer expressed a similar disillusionment saying he now feels guilty for helping with access. “To a large extent you are lying,” he adds.

Last year Oxford’s St Johns college, committed to publicly scrutinising its colonial past. It is the only college at Oxford which has offered funding to research that investigates the monuments, objects, pictures and buildings at its college that evokes its colonial history. This relatively small two-year project was met with immediate backlash from donors, with benefactors threatening to withhold donations. In this rare public interaction between donors and senior staff at Oxford, we begin to see where the problems really lie.

Five years after Chumani Maxwele’s “poo protest”, Oriel College finally voted in favour of removing the statue of the Victorian imperialist who was responsible for the slaughter of thousands of Africans. But the conversation does not end here.

Oxford is at the very beginning of a journey with which it must reckon with its violent colonial past in order for it to ever commit to any kind of anti-racist politics. The issues here transcend diversity quotas and anti-bias training seminars, that will only ever scratch the surface. The university needs to look inward and see the ways in which white supremacy are imbued in the very fabric of its institution. Some have argued that Oxford can be reformed, others have demanded a more radical dismantling of the entire institution through the redistribution of its obscene amounts of wealth. Either way, it cannot continue to exist in its current form, that does little else than exacerbate societal inequality and harm its own students.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?