Nadia Akingbule

Remembering Pearl Alcock, the Black bisexual shebeen queen of Brixton

Jamaican artist Pearl Alcock ran underground gay bars, made outsider art and created crucial spaces for the Black queer community in 20th century London.

Oluwatayo Adewole

02 Feb 2021

It’s Saturday night in 1977. Let’s head to Railton Road, in the heart of Brixton. The street is part of an area known locally as ‘The Frontline’, and there are a few more nice cars than you’d expect in this part of town. On the south side of the road is The George pub, where there are signs of life, despite it being Saturday and thanks to a notoriously racist landlord – the clientele is wholly white.

But if you listen closely, you can hear the faint thrum of bass coming from somewhere nearby. If you were to follow the sound and knew the right people, you’d end up in the basement of a bridal shop at 106 Railton Road. There you’d find a shebeen – an unlicensed bar – filled with Black men. Some are dancing close with one another, bodies intimately entwined in a way they could never dream of being outside, on the streets of Brixton. Others are shooting the shit; there’s bar regular Leroy Arscott, talking about Castro and Cuba again. And behind the bar’s shabby counter, holding court, is the woman behind it all, the Black bisexual queen of Brixton: Pearl Alcock.

Born Pearlina Smith, she grew up in Kingston, Jamaica. Pearl’s life before she came to the UK is mostly a mystery, but she did have a French-Canadian husband who was left in the Caribbean when Pearl migrated to Leeds aged 25. While there, she worked as a maid and in the factories until she saved up £1000 to be able to open her own shop in London. Around 1970, cash in hand, she made the move down to Brixton and launched a women’s clothing shop at 106 Railton Road.

Sometime in the mid-1970s, Pearl started her shebeen, in the basement of her shop. Most of her clientele were Black gay men from the Caribbean, many of whom were her friends, although some white faces could be spotted, mostly men from the nearby gay squat, wryly named ‘The Brixton Faires’. The shebeen was predominantly a Black gay space, which made it unique amongst the underground bars that populated the city.

At the time, Pearl’s sheebeen was the only gay bar in Brixton, which meant it attracted Black men from all around London who wanted to enjoy themselves in a queer space without the racism common in the predominantly white gay scene at the time. Plus, the other option for locals on Railton Road was The George, renowned for its racism and homophobia with both “Blacks and gays” banned from entering. The pub was burned down in the Brixton riots as an act of “revenge”.

David Warner, a regular patron of Pearl’s, said that as a proprietor Pearl was nice but “took no-nonsense”. “Her prices weren’t exploitative, you could get a half-pint of Heinkeken for 50p,” David recalls, noting that there was never any violence there. People just socialised and had a good time to the music Pearl chose from behind the bar, or the records customers brought from home for her to play. Dirg Aab Richards, a longtime friend of Pearl’s, says she was a “big smoker” as well as a “kind and generous” person, always “full of laughs”. When Dirg knew her, she was very much out and proud – he remembers her proudly proclaiming “I’m bisexual ya know!” to a straight friend of his.

Unfortunately, the good times couldn’t last. With the election of Thatcher in 1979 and the heightened moral panic over “traditional moral values” beginning, the police started to clamp down on shebeens. To avoid having herself or her customers experience the violence of an inevitable police raid, especially as Black and queer people were especially vulnerable to brutalisation at the hands of law enforcement, Pearl stopped selling alcohol at the turn of the decade. David Warner remembers that regulars at the shebeen moved onto other places outside of Brixton, which for him was a bar in Clapham. There wasn’t another gay drinking venue in the area for several years.

By 1981, Pearl’s shop was financially untenable, as customers stopped calling in the wake of the first Brixton uprising. Making the tough decision to close the business, Pearl moved next door to 105 Railton Road, opening and running a cafe in a building owned by relatives of hers. The cafe wasn’t particularly grand or fancy, but that was part of its charm; it was a “safe haven”, according to Dirg Aab Richards. You’d be there, packed in like sardines with a bunch of other people from the local community who were mostly West Indian.

“She was very much out and proud – Dirg remembers her proudly proclaiming “I’m bisexual ya know!” to a straight friend of his”

Dirg would sometimes sit there for hours, sipping coffee as he listened to Pearl weave her tales about the old days in Jamaica. On a good day, she would even make patties. Most people learned about the cafe after a recommendation from a friend, so there was a tight-knit network of regulars. Over time, the place became more run down as finances grew more stretched; towards the end, the cafe even had its electricity cut off. Marilyn Rogers, a fellow artist who knew Pearl recalls that even in those waning days living by candlelight, Pearl’s cafe was still occupying the role of a unique space for people in the community. It was a place to come together in spite of the deprivation and struggle which surrounded them. The cafe eventually closed in 1985.

That year also marked Pearl’s start in creating art. On the occasion of a friend’s birthday, she used crayons and packaging from women’s tights to create a card. This was well-received, so she started to sell bookmarks for a pound each, also made from packaging inserts. In a 1991 interview with Mark Kurlansky she told him that: “Everything I [got], I was scribbling on. The receipts at the cafe. Everything… I couldn’t stop working.”

Both Marilyn Rogers and Dirg Aab-Richards talked about how, particularly at the beginning, Pearl’s friends supported her artistic endeavours by buying materials for her, or even buying her work. Richards remembers paying £50 for one of her early art pieces.

Her style, Marilyn says, was authentic, spiritual and representative of her Caribbean roots. That was a reflection of her life; while she wasn’t deeply attached to a specific faith, Pearl was a very spiritual person – Marilyn notes that she “always left an extra plate out to give thanks” when she made food.

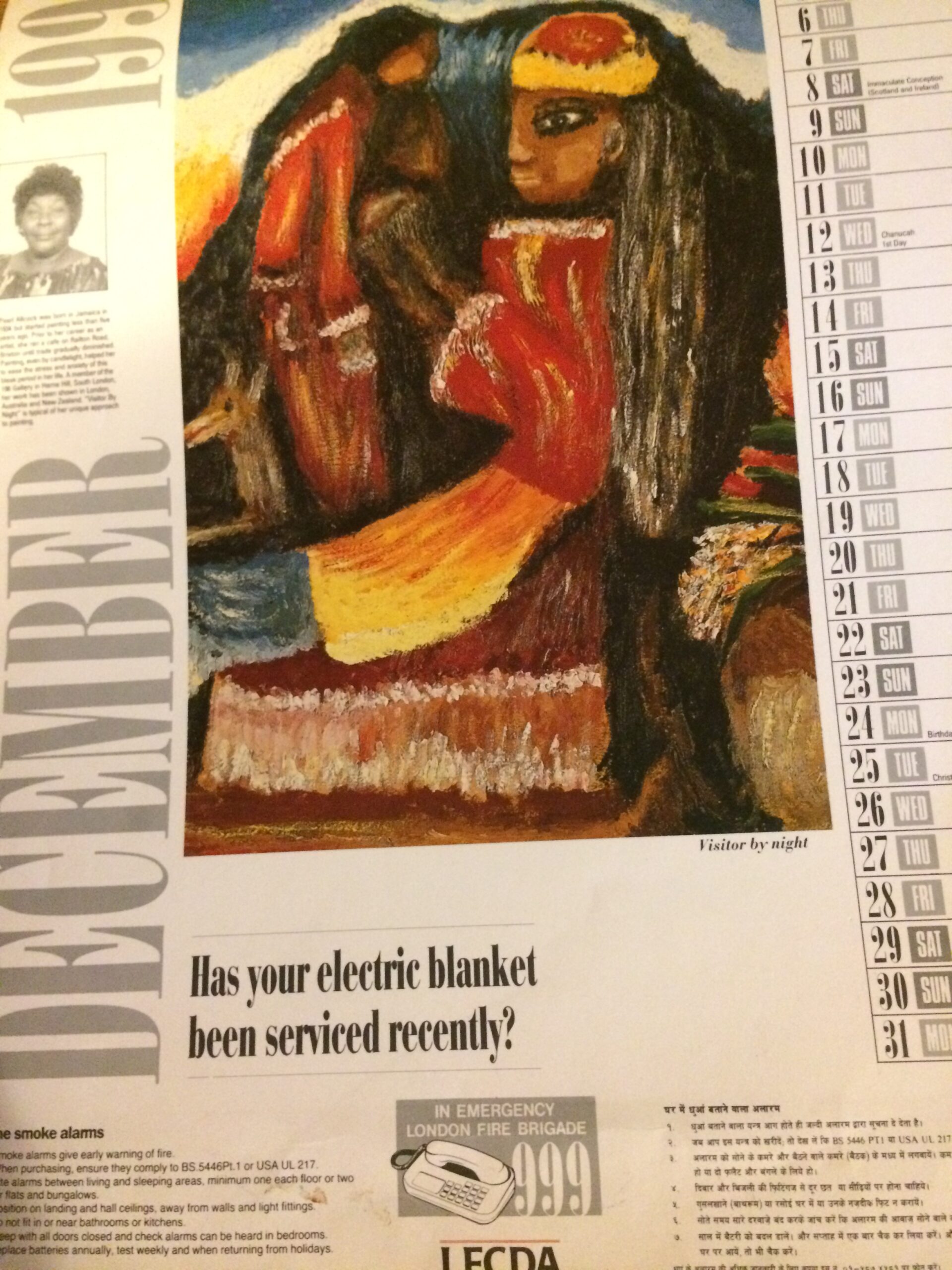

As Pearl’s work got more attention, she moved onto bigger pieces. She flitted between the abstract style of her paintings that were beginning to be shown in galleries, and a more commercial aesthetic, like making postcards to sell under railway arches. From the late 1980s onwards, her art was exhibited in the 198 Gallery, the Almeida Theatre and the Bloomsbury Theatre.

Andreas, a friend of Pearl’s, says that she was “self-deprecating about her work” but they remembered “seeing her pleasure” when she was included in the 1990 London Fire Brigade calendar. It took until the year before her death for Pearl’s work to get mainstream recognition, being shown in the Tate Britain as part of their ‘Outsider Art’ exhibition in 2005. In 2019, she was the subject of a year-long retrospective at the Whitworth Gallery in Manchester.

Pearl kept making work until she died aged 72, on 7 May 2006. Historian Milo Bettocchi tells me that even to Pearl’s dying days she lived in the St George’s Residence Housing Co-op – just across from where her infamous shebeen was. She got a big send-off too; according to Milo there was a “lovely turn-out” at her funeral.

Pearl Alcock’s story mirrors the life of so many of our Black queer elders. She didn’t fully get her roses when she was alive, and even with the renewed interest in her path, it’s too late for much of her story to be told in full. Black queer folk who hold oral histories and came of age in the 20th Century have often passed on – sometimes prematurely, due to complications from HIV/AIDS. Buildings have been demolished and it’s very rare that the Black queer community has collectively had the access or finances to ensure our stories are preserved in conventional ways. Both Pearl’s shebeen and cafe are just private homes in Brixton now.

That doesn’t erase her impact. Pearl created a space like no other, which is near impossible to replicate – especially as gentrifying forces dig their claws into Black communities. She withstood the forces that always try to erase us, from the moral panic of Thatcherism to persistent misogynoir. In the midst of all that, Pearl made some brilliant art, all while showing love and generosity to the people around her. Her legacy remains. When you live a life defined by giving, you can never truly be forgotten.

Thank you to Dirg Aab Richards, Marilyn Rogers, The Brixton Society, David Warner and Milo Bettocchi for their contributions to this remembrance.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?