Stephen Tayo’s photography brings Lagos’ underground drag scene out of the shadows

What If is Stephen Tayo's exploration of how LGBTQIA+ people could live if Nigeria let these queens live out loud

Woju Aderemi

19 Mar 2021

Photography by Stephen Tayo

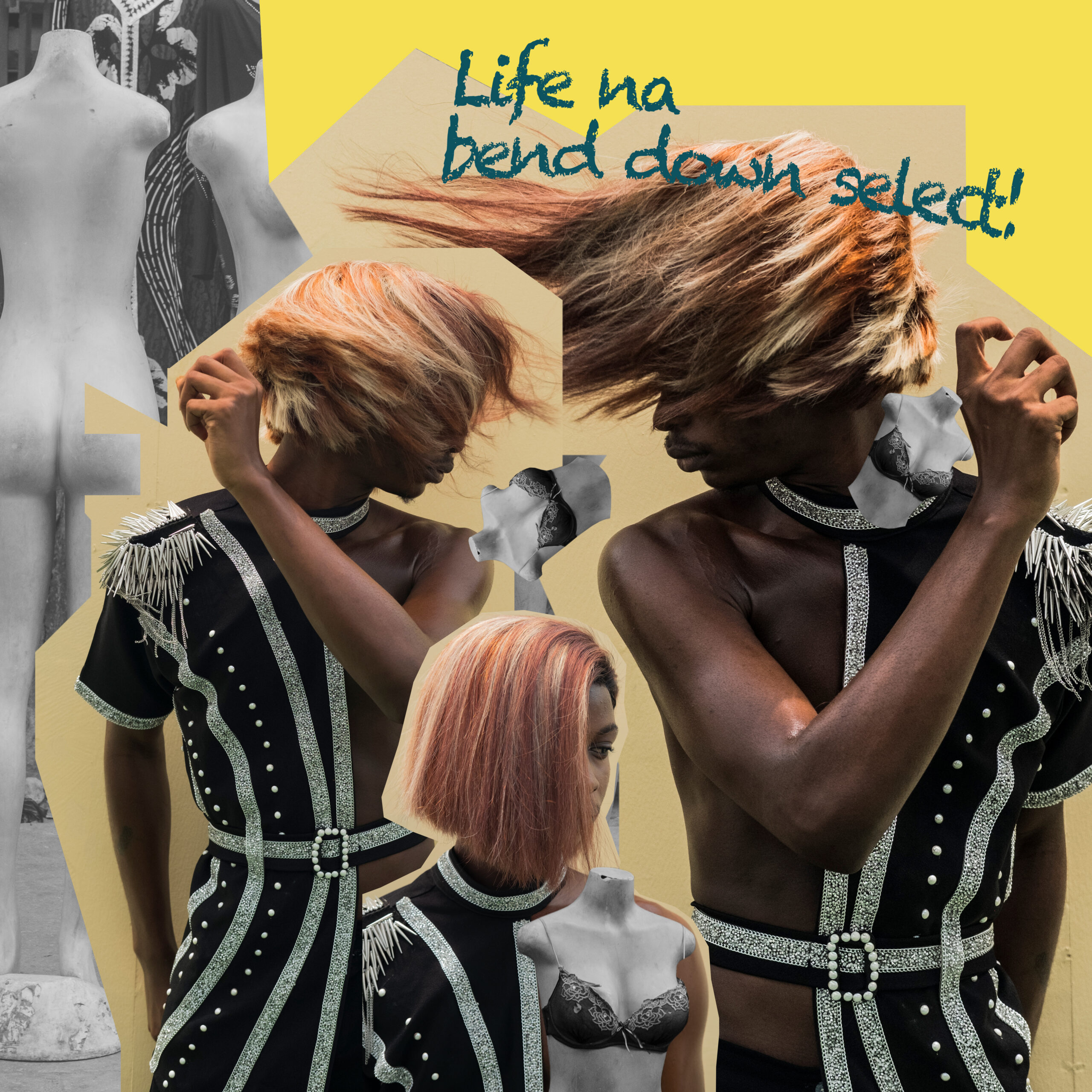

The photo series What If is a mood board for the egalitarian future Nigeria should aspire to. It is the proud collage every queer Nigerian teen wishes they had pinned up in their room, a visual representation of their fantasy of being able to live their truth freely. Constructed by Lagos-based photographer Stephen Tayo, the series boldly asks: “What if our society didn’t ostracise queer identities?”

While Britain is still reeling from the results of UK Drag Race (still hurt), which airs on a major broadcaster, Stephen Tayo, renowned for his storytelling imagery, introduces the world to drag artistry in a deeply homophobic space. He started working on the idea in 2018 and has already been exhibited in Lagos’ kó art space earlier in 2021. “A lot of people always want to show their work out of the country, but I think, especially for this conversation, I was really glad that I could show it in Lagos first.” Now it will be shown at Amsterdam’s Framer Framed Art Gallery from March 18, where Stephen will take part in a discussion that reveals his process and share a glimpse into the lives and friendships with the subjects on display.

Originally, he was motivated by the risk involved in pursuing this art form. “[Some people] might have some sort of reservation around it,” Stephen points out, however, there is a high incidence of physical assaults on Nigeria’s queer community. Deeply traditional and religious, Nigerian society is actively hostile towards the LGBTQI+ community. Its criminalisation of “public shows of same-sex amorous relationships” under the 2014 Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act empowers intolerance, resulting in the marginalisation of queer lives and a constant danger and fear of violence on queer people. A 2020 study investigating police violence targeting LGBTIQ+ people in Nigeria found that violence and human rights violations against LGBTIQ+ people had increased by 214% between 2014 and 2019. In 2019, 344 men reported human rights violations, in comparison to 53 reported violations against women.

Despite this, Lagos (Nigeria’s commercial capital) plays host to talented underground performers – namely, Naija Black Barbie, Onyx Godwin, Remilekun, and Jay Boogie. Though all the images obscure their faces – a protective precaution that also emphasises their against-the-grain artistry – What If is a window into the worlds of these artists who have been condemned to the fringes of society.

Naija’s Black Barbie is a fashion queen. Photographed in a blunt, asymmetric multi-toned blonde wig, the ‘Lagos Diva’ is styled in a halved collarless dress shirt, complete with a pearl belt-buckle detail, fringed shoulder pads and textured silver contrasting. Onyx Godwin and Jay Boogie are equally flamboyant, accessorising their rich hues with statement headpieces – a feathered fascinator for Onyx and a fringed sun hat on Boogie. Another “what if” Stephen questions with the series is what these unsung stars could achieve “afford the life they want to live.” Rather than just setting his sights on a rousing exhibition, he aims to look for grants from global brands, such as FENTY and MAC Cosmetics, to platform and support these make-up loving drag artists.

Their faces are hidden throughout the series, for their protection. But from the wig details to sneak peeks of bronzed faces, as Stephen’s priority is to uplift and support these queens. “That’s literally the focus right now for me, which is why I’m trying to exhibit the work in a more accepting place and community,” Stephen Tayo reveals as we sit down to discuss the project’s coming together and its exciting future.

“There are people who derive happiness [from drag], and there are people who do it for clout and social media – the latter group are the ones that are safe”

The 26-year-old photographer makes it clear his intention is not to force people to conclude that everyday Nigerians are “narrow-minded” – “I’ve never felt people are. I just think people know what they know, and they want you to see life as they know it,” he explains – Stephen is intent on provoking Nigerians to have the conversations that they don’t usually have, to interrogate their biases. For example, he’s critical of the fact that drag is popularly accepted as a punchline by Nigerian comedians, who mimic drag queens to rally up laughs (and their audiences never fail to laugh). Still, as a lifestyle, drag is punishable by law. “There are people who derive happiness [from drag], and there are people who do it for clout and social media – the latter group are the ones that are safe,” Stephen says. “It’s worth talking about.”

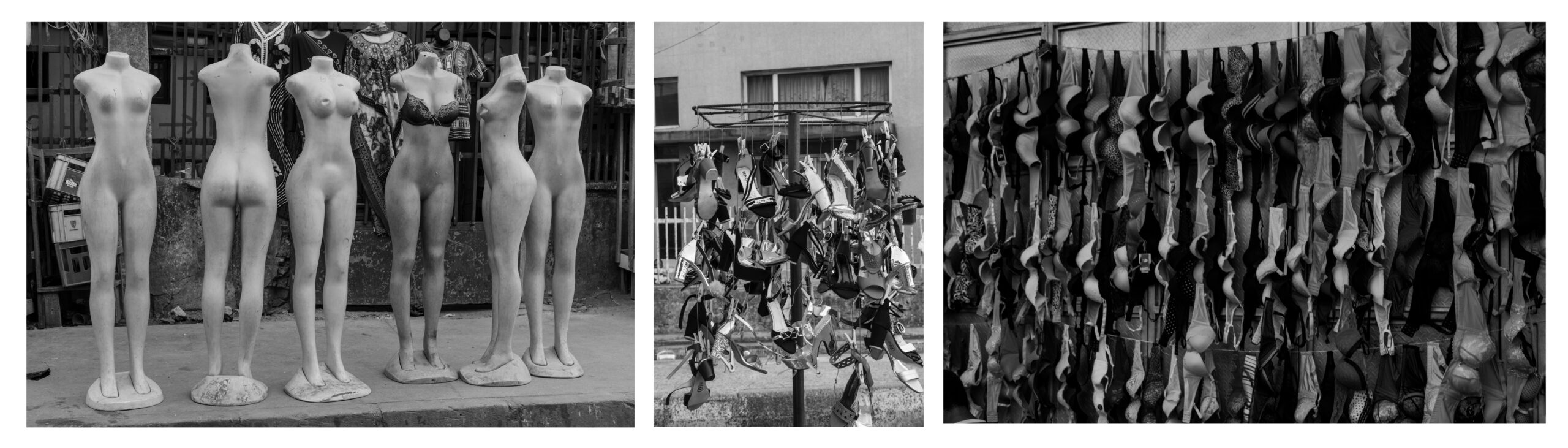

Having studied Philosophy at university, Stephen’s photography is renowned for its subterranean layers, communicating complex human stories from the world around him. For Ibeji (2019) Stephen captured the mystical bond of twins that is often shrouded in mythological legend in his Yoruba culture. While one of his most defining collections, What It Means To Dress In Lagos, for the New York Times, exposes the sartorial obsessions of Stephen’s home state, as he photographed Lagosians across class, gender, sexuality and age boundaries donning the clothes that speak to their truest selves. He lensed the likes of style-icon-turned-rapper Deto Black in her shimmery three-piece ensemble that portends the star she will be, and hairstylist Raymond’s bright orange space puffs, simultaneously complementing and contrasting his sea-green contact lenses – a combination illustrating his “Unique Touch” (his salon’s name).

But unlike his other projects, What If unearths a world to which many Nigerians are unfamiliar. Some physical spaces exist for drag artists in Nigeria. In Abuja, the scene is a lot more structured. It’s an open secret that there are clandestine provisions from some (possibly closeted) politicians who fund drag queens and help them with accommodation, meaning there are more spaces to perform drag without fear.

As well as learning about these kept queens, Stephen’s series also showed him that while Nigerian society publicly shuns them, privately an extra stream of revenue has been sex work from politicians and heterosexual couples alike. “One of the people who I photographed said to me, that all through 2019 he had couples, would invite him over, so he’d serve as an enhancer during their sex,” Stephen says.

“One of the people who I photographed said to me, that all through 2019 he had couples, would invite him over, so he’d serve as an enhancer during their sex”

Marginalised IRL, these drag artists have found a haven in online communities, where they are free to share their artwork with a lower risk of harm and greater opportunity to connect with other drag artists, in the country and around the world. For others like Naija Black Barbie, Onyx Godwin, Remilekun and Jay Boogie, and prominent LGBTQIA+ Nigerians (“Bobrisky and James Brown,” Stephen names) – Instagram and other social media platforms are empowering tools for them to freely express themselves.

Online Remilekun displays her skills as a professional make-up artist, Onyx shares her fashionable moments through her clothing store, Rude Krush. Black Barbie’s page boasts a plethora of talents, she hosts many TikTok videos that simultaneously flaunt her dancing skills and boost the songs attached to them; modelling shots for designers and wig brands alike; and witty skits advertising her skincare products. Online spaces have empowered the muses of What If, and enabled them to celebrate themselves within the public sphere, though it still remains a life-endangering pursuit even when done from behind a screen.

October 2020 marked a pivotal point in Nigeria’s history, not because of her 60th birthday, but because the EndSARS protests. One of the often-heard excuses for harassment at the hands of SARS officers is that their victims “look gay”. Stephen was at a critical stage in his process when EndSARS struck. Equipped with all the images but still deciding on the direction he would take with the series, the protests inspired Stephen towards “some sort of activism in the context of the work.”

Stephen appreciates that “the story, even, is a form of activism, for actually putting [drag] out there”. From their private, off-grid gatherings, to the Arthouse Ikoyi residence to kó art space and now Framer Framed in Amsterdam, Nigeria’s drag stars have travelled well beyond the confines of Nigeria’s hyper-religious society. They, and Stephen, are excited to see what the future holds for their subculture. What if they continue to build an openly visible LGBTQI+ community in Nigeria.