Meet the Nigerian tailors preserving their craft on London’s high streets

Inspired by fashion within her family, Sadatu Futa visits three women whose tailoring shops have stood the test of time.

Sadatu Futa

17 Oct 2022

Sadatu Futa

My mother, Mariama, sings decades of praise for her tailor. In the sound-spaces of gatherings, African women will be heard sharing similar compliments for their tailors. It’s easy to see where this praise comes from, especially during ceremonies where all in attendance are expected to wear a uniform fabric selected by the host months in advance. It’s a tradition known in my Ghanaian Hausa community as yayi, or aso-ebi in the Nigerian Yoruba language. Working with the yayi, African women tailors fashion bold balloon sleeves, tasteful side-slitted dresses and off shoulder peplums, revealing the characteristic beauty of each wearer.

The Heart of Race, a book by Stella Dadzie exploring Black women’s lives in Britain, details the opportunities that sewing and dressmaking provided for Black women facing challenges finding work due to immigration, racism and systemic inequality. Similar to the women seamstresses of the Windrush generation before them, growing numbers of Black African women settled in Britain from the 1980s onwards and utilised their sewing skills.

These entrepreneurs from Nigeria, Ghana and Sierra Leone started tailoring businesses, threading through webs of inequality to attain economic independence and work which allowed time to also carry out family responsibilities. For the diaspora fragmented from home, West African women tailors actualised a sense of belonging and social cohesion in the intricate textures of design.

“For the diaspora fragmented from home, West African women tailors actualised a sense of belonging and social cohesion in the intricate textures of design”

Inspired by my namesake, Hajia Sa’adatu Futa, an accomplished tailor in my family who passed away a few years ago, my mother’s overflowing wardrobe and my spoken word film, God of Thread, which was shown at the V&A Friday Late x GUAP African Fashion Takeover, I spoke to three Nigerian women tailors in London about their journey so far, their triumphs and the challenges that lie ahead.

Grace of African Fashion – Rye Lane Market, Peckham

While adding straps to a dress, Grace, the owner of Grace of African Fashion pauses to comment on Stella MCartney’s ‘African-inspired‘ collection which the British fashion designer released on a line up of white models during 2017’s Paris Fashion Week. “Because she has [that] name, she was selling them for £2,000 plus. Here I sell [authentic clothes] for £60.

Grace, a petite woman, requires a long pole to reach the ready-made designs hanging on the walls. Overwhelmed with the piles of clothes stacked in blue plastic bags and trolleys, she tells me about customers returning months late to pick up orders, and the extra labour of having to search for their clothes. Grace also sells pure shea butter, soaps and body creams in the shop. When I ask about hyperpigmentation on my skin, Grace picks up a green container placed on the table behind her workstation, a £5 Alata soap made in Ghana.

In 1968, when Grace was learning how to sew alongside her studies in Nigeria, she faced the disapproving eyes of her Nigerian community which had different perceptions of success. For young girls, a future in secretarial jobs was viewed as the ideal. Today, glammed up in red lipstick and a matching knit cardigan, Grace shines brightly as she challenges the devaluing of tailoring skills. Grace is backed up by her business’ success – after all, it gave her the freedom to walk away from the nursing career she started in 1995.

Despite the lack of government support and minimal resources to hire more staff, along with a more than 60% increase she’s noticed in the price of thread since February 2022, Grace’s faith remains immovable. “When you think you’re going down, you say ‘I will be alright’.”

“‘I am giving you more than I give to others,’ Grace says, when she consents to a photograph”

When I ask about fast fashion, Grace narrates her wardrobe history, expressing her joy when people compliment her on pieces dating back from the 1980s. She pokes fun at the attitude she says young people have towards repeating outfits. “‘I can’t wear it, man!’” Grace says, delivering her best impression of young people. But she is eager to share her experience with them and wants young people to know her doors are always open for volunteering.

“I am giving you more than I give to others,” Grace says, when she consents to a photograph. This undeniable truth reflects my location as the outsider-within – a theory proposed by sociologist Patricia Hill Collins to name the unique standpoint of Black women working in white fields. As we work together to ensure she’s comfortable, I think about how Grace’s control over her images is a far cry from the violence that photography has historically wielded over the images of African women. “I will sit on my machine so that people will know my handwork,” Grace says, positioning herself and subtly smiling into my camera lens.

Roseline Elegant Fashion – East Street Market, Walworth

When I arrive at East Street Market in Walworth, South London, on a Monday morning to interview Rose, the designer at Roseline Elegant Fashion, she’s very clear about what she wants – or doesn’t want – my images of her to show. “Don’t put my face,” she tells me.

The all-white interior design lighting her shop enhances the materials folded on the shelves, including a customised pink party bag that reads ‘Titilayo at 70’. In the shop window, one of three displayed mannequins is beautified in a pink and gold peplum lace top.

Once a student at the Singer School of Fashion in 1994, Rose reveals her passion for learning and dreams of teaching her craft. “If someone helps me through that dream, I will be happy,” Rose says. Her teaching dreams guide our conversation: I become her student as she eases into step-by-step explanations of the hook-and-eye method of securing garments. I listen attentively as Rose explains, allowing the camera to take notes.

Rose is passionate about youth work, “especially young girls like you,” she tells me. In 1994, she had to drop out of fashion school because she struggled to pay the fees. She recalls her persistence to continue learning and an appreciation for her younger self. Rose’s persistence was rewarded in 1995 when she boldly approached a woman at a tailoring business with one question: “Can I come here for some practice?”

Rose became one of 24 workers at the business. Taking note of her strong work ethic, the other workers attempted to take advantage of Rose by piling extra work on her. But Rose, always a step ahead, had a different perspective. “They were thinking they are using me, but I was learning.”

In Rose’s business, multi-tasking is key. Expecting a customer through the doors soon, she continues to teach while adding finishing touches to the customer’s blue and gold sequin dress. I also learn about her extensive knowledge of fashion throughout the continent, from the Ghanaian fugu, to the Nigerian aso-oke, to the Guinean brocade.

With event cancellations, and the nature of the job – measurements, fittings and amendments which require in-person appointments – the pandemic was a tough time for the women tailors. When Rose received a government grant to help support her business weather the storm of 2020, it went straight to the landlord of the businesses premises at his request. “I don’t want any trouble”, she says, wanting to protect her peace.

AdeFashion Couture – Plumstead Road, Woolwich

African women tailors are one of the unnamed casualties of the displacement caused by gentrification. According to data from The Office for National Statistics, rent has increased by 3.2% in the last year alone, the fastest growth since 2016. This increase in rent prices brings in property developers and businesses with economic and political power, pushing businesses run by working class and migrant communities out of sight.

Adesuwa, the owner of AdeFashion Couture on Plumstead Road in Woolwich, received a get ready letter last year. In 2023, the Woolwich Exchange Development will begin construction in the area which will involve the demolition of her shop. An experienced business woman, Adesuwa previously ran a restaurant in Spain, and appears to have made peace with the upcoming changes. “The option is just to find another place,” she says.

It’s a Wednesday morning, the ground floor shop is filled with the sounds of Adsesuwa’s sewing machine piercing through a white lace fabric. Adesuwa’s cornrowed hair frames her face, but she prefers her hands and work to be photographed. Adesuwa’s light spreads through the room, even as she is engrossed at the machine. It is no surprise to learn that her customers, appreciative of her service and work, supported her during the pandemic.

Adesuwa has been sewing for 35 years. In 1987, she was one of five students of a strict Madam in Benin City, Nigeria. A Madam is an experienced tailor who takes on apprentices to train at her business – the apprentices gain a craft to sustain themselves in the future, and the Madam benefits from a helping hand. Adesuwa, a quick learner, mastered the craft in less than two years. Today, Adesuwa is a Madam at her own business. Her apprentice, Ify, sits at a workstation next to Adesuwa and speaks warmly about her: “She loves her work, that is why I’m here.”

Ify tells me Adesuwa dislikes waste, pointing to a storage box filled with unused and leftover fabrics on the other side of the shop. “We don’t throw it away,” Ify says. For all the tailors, recycling and repurposing left-over fabrics is an important commitment.

African women tailors on high streets are a pivotal part of London’s cultural heritage and landscape, and the traditions that they are continuing for diaspora communities must be protected. During their busiest periods, families from all over London come in with hopes of their children being best dressed for cultural days at school. They contribute to the art world, and teach us valuable lessons on sustainability in their commitment to recycling and repurposing leftover fabrics. The tailors serve a customer base of artists who purchase left-over fabrics and they are also teachers and mentors who pass on their craft, stories and joy to the communities who walk into their premises.

Grace, Rose and Adesuwa share common threads in their dedication to their craft, despite the minimal support they receive and challenges they face. They have had to pull from their own inner resources, and are still sustaining themselves in the face of increased living costs, gentrification and a pandemic. The disappearance of African women tailors on our high streets would be a loss for every one of us – but the resourcefulness of these three women gives me hope that the craft, skills and wisdom will endure against the odds.

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.

Boohoo’s attempts to appear ethical are empty and damaging – we must keep calling them out

How the politics of representation mask fashion’s unethical underbelly

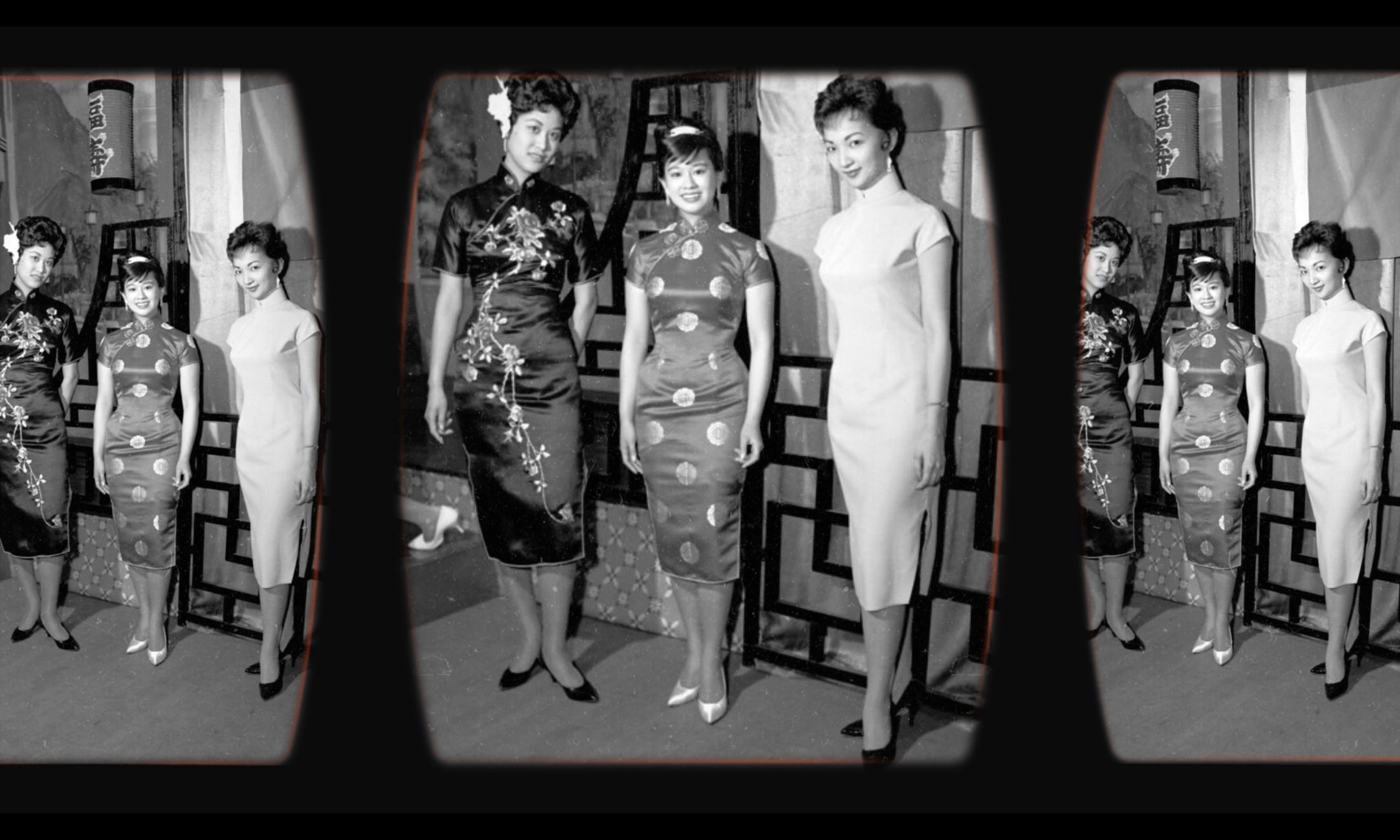

When will fashion brands stop sexualising the cheongsam?