Priyanka Raval

After the freeing of the Colston Four, Bristol celebrates with trepidation

The Colston Four's victory sets a heartening precedent – but can it be harnessed?

Priyanka Raval

08 Jan 2022

“Didn’t you say you were going home to ‘file your pieces?’” said Martin Willoughby, father of the Colston Four defendant Sage Willoughby, yesterday evening, looking at the pint of cider in my hand. I laughed in response and admitted that, indeed, my self restraint had failed me.

But landmark trial verdicts don’t happen everyday. And I’ve got skin in this particular game, – as a born and raised Bristolian and now as a local reporter. Growing up, I’ve watched repeated pleas, petitions and campaigns to local authorities to remove the vestiges of veneration to the slaver Edward Colston that Bristol still wears today.

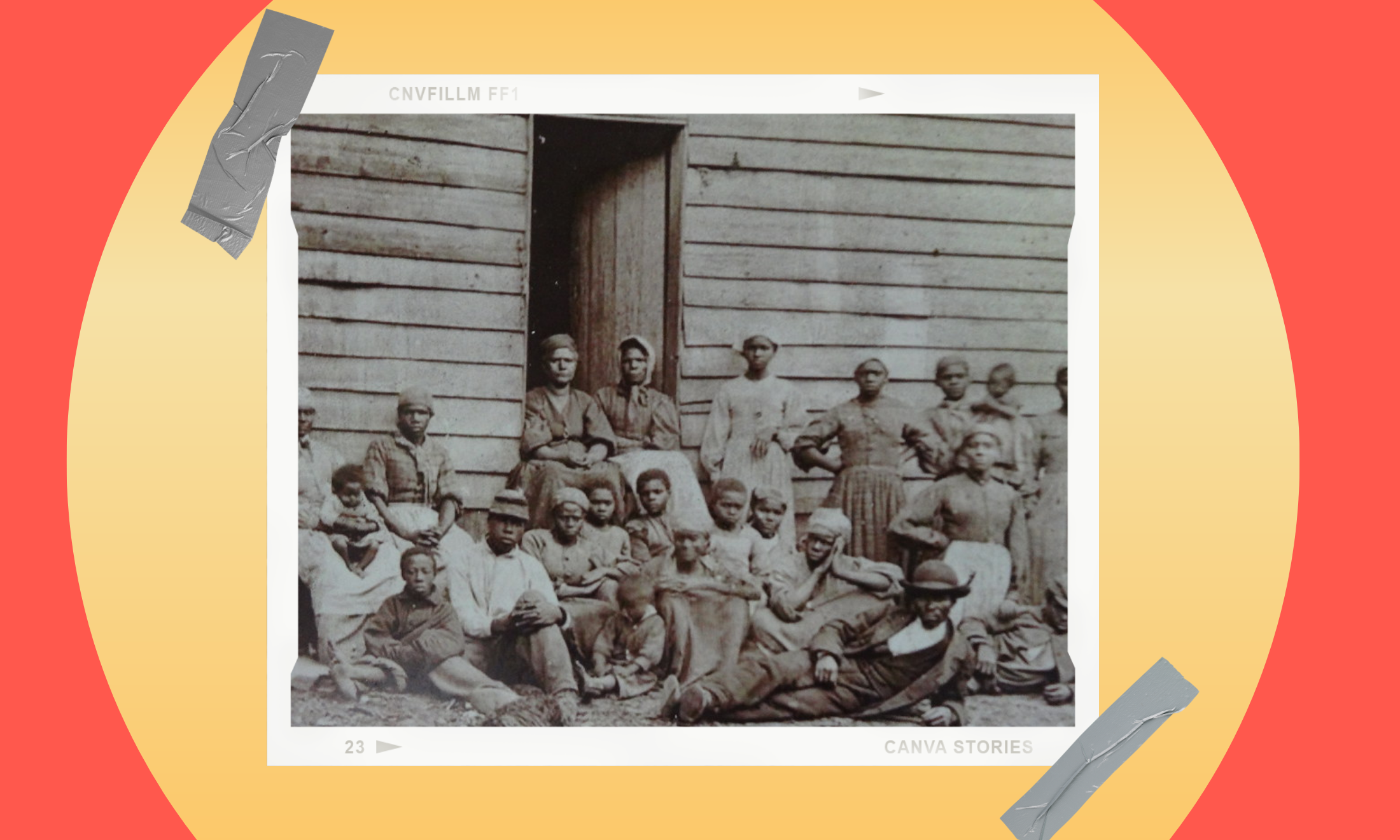

As both a member and later deputy governor of the Royal African Company (the ‘royal’ gives a clue as to who was his boss), Colston was responsible for the trafficking of roughly 84,000 enslaved Africans. It’s a legacy not to be celebrated. But Colston’s contributions to Bristol’s expansion (as a key trading port for the fruits of the slave trade) meant his name was etched into the civic fabric of the city, from concert halls to Colston’s bronze likeness that stood for 125 years – gazing imperiously over the harbour through which his company’s ships came and went.

Until 7 June 2020 that is, when the statue was pulled down from its plinth and rolled into the harbour during a Black Lives Matter protest. I watched it happen; the crowd were ecstatic, shocked, pumped – nothing like the “mob” that they’d go on to be portrayed as by some politicians. The toppling had seismic effects, which reverberated around the world.

But that wasn’t the end of the story. Despite the large crowds involved in Colston’s felling, police sent the cases of just four people to the Crown Prosecution Service, to be charged with causing criminal damage. After charges were brought, these four entered a plea of ‘not guilty’, choosing to be tried in front of a judge and jury. Sage Willoughby, Rhian Graham, Milo Ponsford and Jake Skuse became known collectively as ‘the Colston Four’. On 5 January 2022, the jury reached their verdict in just three hours: not guilty for all the defendants.

Which is how we find ourselves laughing, jostling, jubilant in a local pub, a photographer requesting we assemble for a group photo. Defendants at the front, flanked by friends, proud partners and parents. Their barristers stand behind, legal etiquette left in the courtroom Campaigners from the Glad Colston’s Gone, Bristol Defendant Solidarity, Countering Colston and other activists who’ve worked tirelessly in support of the Colston Four for the past year, squeeze into shot. And there’s one or two of us reporters who’ve been following the case, the energy and excitement of which has bonded us all into a kind of pseudo-family.

We were in the Star and Garter, a cosy community establishment in Montpelier, one of Bristol’s residential neighbourhoods. Above the bar reads a sign, “More blacks, more dogs, more Irish.” In fact, Sage had mentioned this pub in court, having grown up down the road from it. “I lived in a very diverse area, there’s a Christian church, a Jamaican pub, and a Sikh cornershop which I used to work in,” he said.

“When you are surrounded by people of all different cultures you feel like these people are your friends and family and when these people are hurt you feel like you are directly affected.” The prosecution barrister put to him, his actions were an act of violence. “No, the statue was a hate crime […] This was an act of love,” Sage returned.

“Why was the Society of the Merchant Venturers, a body of Bristol’s unelected elites, themselves descended from slave traders, allowed to block multiple attempts to remove the statue?”

In that pub, on that night, we felt that all of Bristol was in celebration, that we were finally on the right side of history. Of course, we knew we were in a bubble. Even as the press and public gathered outside the Crown Court to greet the defendants, a man had started yelling this was an act of vandalism, although he was quickly shooed away. It’s a bittersweet taste of victory, accompanied by a foreboding feeling that backlash is coming. Culture war enthusiasts, from Conservative MPs to the pundit class, have already been trying to stoke it.

For the charge of criminal damage, a lawful excuse can be pleaded. Here, the lawful excuse was that the defendants were found to have genuinely and honestly believed they were acting to prevent a criminal offence from occurring; the statue was a public indecency and caused offence. Further, to find them guilty would have been a disproportionate interference in their right to free speech.

From the witness box, Rhian spoke of the moment before the statue toppled when she and the others congregated. She felt moved by a black man urging them not to remove the shroud that had been placed over the statue – he couldn’t bear to look at Colston’s face, he’d said, not today.

“The statue felt like a hate crime,” said Sage Willoughby. “It was a monument to racism.”

Again and again throughout the trial came the horrifying tally of Colston’s crimes was repeated like a mantra: 84,000 Africans trafficked, 12,000 of those children, 19,000 died on route. Historian David Olusoga, called as an expert witness, called these figures conservative estimates.

Claims of the statue toppling being “anti-democratic” and akin to “mob rule” are also interesting. As has been well reported, democratic channels to remove the monument had very much failed to listen to the will of the people. Protests raging against the statue since 1920 had been ignored. “Our communities raised our concerns, we made petitions to the Bristol City Council in the 1990s – and it was ignored,” said witness for the defence Lloyd George Russell, who is of Jamaican heritage and can trace his ancestry back to the descendants of slaves. “Black people in the city just aren’t recognised.”

“But I’m under no illusions that that hope is held tentatively, and with uncertainty over what comes next”

The story of the Colston Four does show there are questions to be asked about the current, supposedly ‘democratic’ processes in place. Why was the Society of the Merchant Venturers, a body of Bristol’s unelected elites, themselves descended from slave traders, allowed to block and intervene in multiple attempts to remove the statue? How can we create democratic systems for deciding our public spaces and our history? How can we ensure that all members of the community are publicly consulted? People only took matters into their own hands when other doors appeared to be closed on their faces.

And as for re-writing history, well: “the statue itself was re-writing history,” one defence barrister noted – pointing to the fact that Colston was a divisive, often hated figure in his day. Funds for the statue failed to be raised by the public when it was first proposed and its erection was contested even at the time.

When the dust has settled, I hope the trial of the Colston Four, will show how, legally, statues for slave traders and mass murderers can be considered a public indecency. I hope it will spark discussion for the need of democratic, locally informed, representative consultation on the design of our public spaces, and the representations of our heritage. I hope people will understand how the symbolic value of statues can have real, material impacts on racism.

But, realistically, this falls in the context of living under a Tory government who dismiss these actions as “Radical left activists”, “Woke worthies” and “Town hall militants”. They use such acts of defiance, and verdicts such as this, to fuel the fire of their culture wars – which owing to a woeful dearth of proper historical education, combined with emotionally ensnaring soundbites, is all the more likely to take root in public debate.

So yes, I am hopeful about the potential for the verdict of this trial to push us in the right direction. I hope people will come to our city, and talk to people here, and understand the specificities of the local context which led to this event. But I’m under no illusions that that hope is held tentatively, and with uncertainty over what comes next.