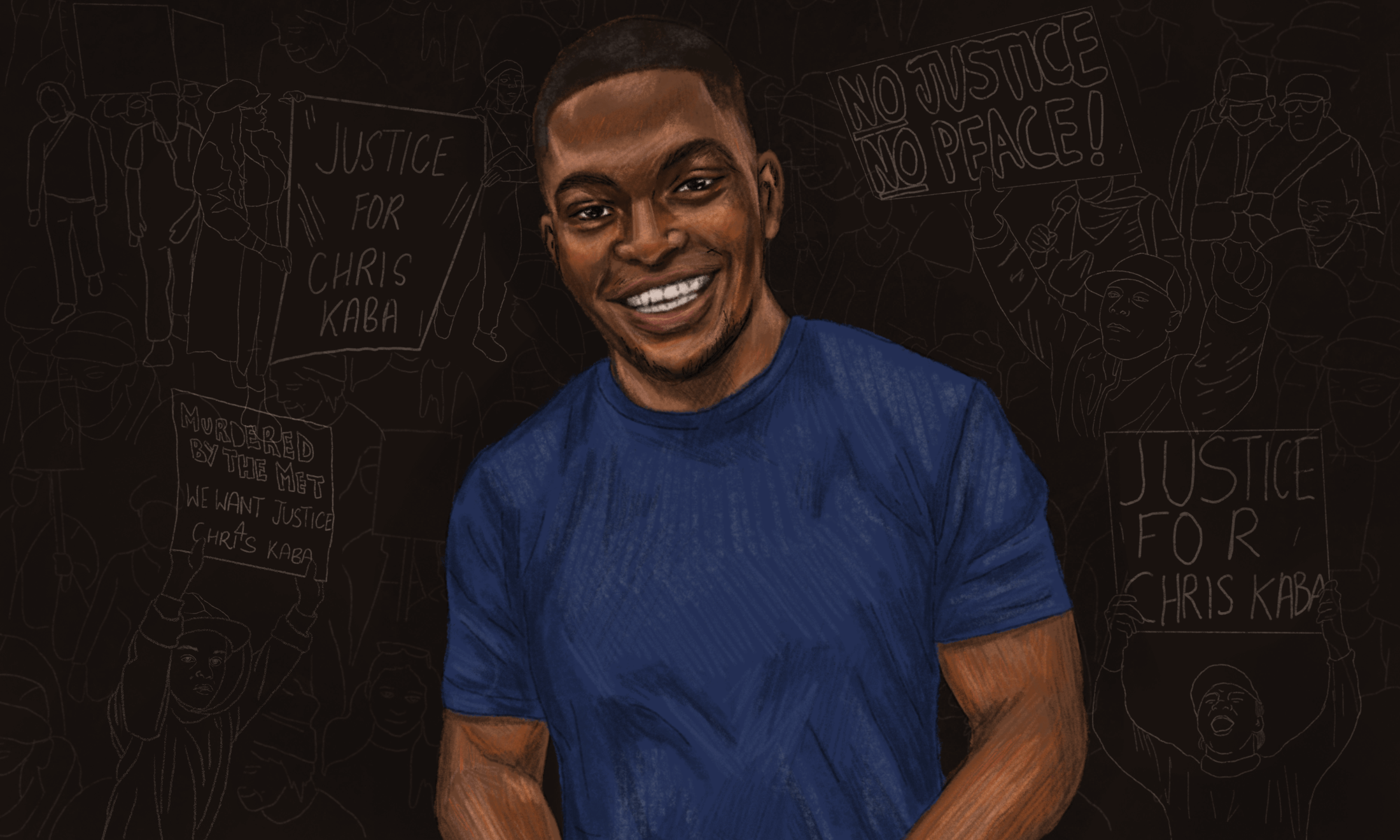

Illustration by Laura Elise Wright

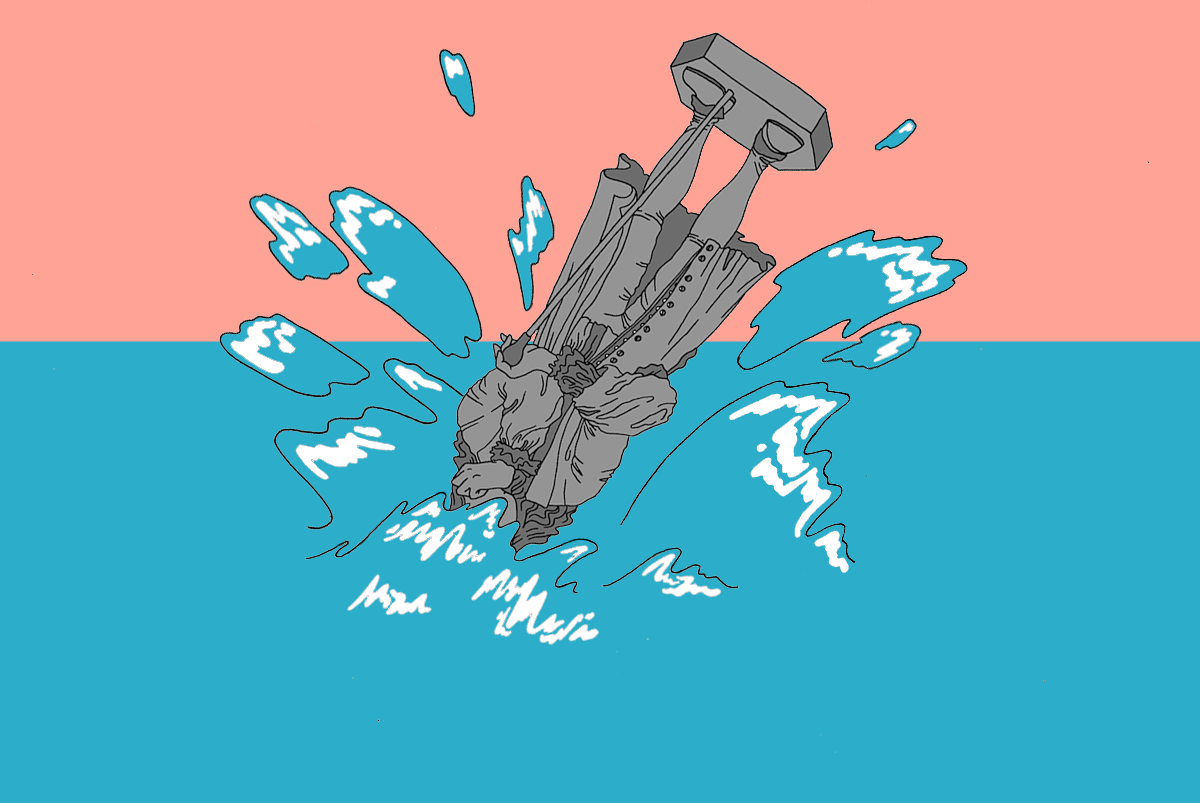

I didn’t think 2020 would have me crying tears of joy at the death of a statue, but here we are

The statue of Edward Colston drowned in my hometown of Bristol yesterday and I cheered, whooped and cried. I imagined that it took with it all the difficult experiences of growing up in the city while Black and queer.

Travis Alabanza

08 Jun 2020

Illustration by Laura Elise Wright

I watched the video of Edward Colston’s statue in my hometown of Bristol being pushed into Bristol harbour around 100 times last night. I giggled at a remix that was made to the backdrop of ‘Roman’s Revenge’ by Nicki Minaj. Then I watched a clip where, as it falls into the water, you hear a notification sound. After that, I watched it in slow motion.

It felt different each time, I think. It fluctuated between the feeling of a sparkle of hope, to the satisfaction of watching a bully getting what they deserve at the end of a movie, to a feeling of pure disbelief. Finally, I felt whatever the word is for the opposite of disbelief: a complete surety in intention and action.

As I watched the videos of Black organisers standing on top of where the statue once was, I thought about what it means to claim space in the midst of resistance. I remembered setting up a space for Black and brown students to gather in my sixth form in Bristol and the whispers from people asking if it was racist. I remembered every club night where people listened to reggae and screamed that they loved Bob Marley while putting food and beer in my afro as a “joke”. I remembered the only gay club that would allow my fake ID and being told they would “let me in, because we need a pretty Black boy”. I remembered all of the times people sat in the specific Bristolian cosy bubble of liberalism – so snug that they could not possibly speak about their racism because it was just something “that didn’t happen here”.

“I remembered every club night where people listened to reggae and screamed that they loved Bob Marley while putting food and beer in my afro as a ‘joke’”

So, what else did I feel I saw the video of Edward Colston being tossed into the waters where he committed such evil, right into the River Avon, which was used in the peak of the slave trade? I felt proud. So proud of the organisers of Black Lives Matter Bristol, so proud of a city protesting, so proud of the removal of a statue that has faced many years of petitions for its removal.

I imagined as the statue fell, that it took with it all the times I had been called n*igger at a football match at Knowle West, the many times I was followed around stores in Cabot Circus and when, after a Rovers game on Fishponds Road high street, someone called me a Black f*ggot. I imagined, as the statue fell, that it took all the difficult experiences of 18 years growing up in the city while Black and queer and smashed them to the ground too.

I imagined it destroying everything named after a slave owner in our city. Down went Colston’s, the independent school that bears his name, the block of flats called Yeamans House and Wills Memorial Building. So too disappeared ‘Colston’s day’, the 14 November, which is set aside for celebrations in Edward Colston’s honour.

I imagined that the statue was tied with the hair of the disproportionate number of white people with dreadlocks in Bristol and that, as the statue was yanked from its plinth, so were the appropriative hairstyles pulled out from their roots. That as the statue hit the ground, the yells of “but I can wear this hairstyle because I’ve been to the Black Swan twice” were overpowered by its clanking.

When the statue was submerged, falling headfirst after being rolled through the street, I imagined the submersion of shouts by white Bristol-vegan-leftists, who think cows are more important than Black people. The echoes of, “It isn’t about race, it’s just the human race” bubbling up from the harbour.

I bumped into a Black queer friend from Bristol on the street and we watched the video together. As it crashed into the water, and the crowds erupted in cheers, we did too. We felt a sense of justice. As if, with the statue falling, Black people can expect change from the city. As if, after years of petitions, name change debates and arguments, we’ve just gone, “Hold my damn purse as I throw this away.” We’re starting again. Letting everyone know that something else must go here; something else needs to grow here.

“After years of petitions, name change debates and arguments, we’ve just gone, ‘Hold my damn purse as I throw this away’”

Already, there is discussion about what must replace the statue. People are thinking about the Bristol Bus Boycott and one of the founders of that movement, Dr Paul Stephenson. Others are talking about replacing it with sculptures or artworks by local young Black organisers and impact makers. But I want fellow Bristolians to pause. I want us to keep the rubble on the ground and to have to walk past it. For it to stay there, dust and all, as a reminder to the promise that was made in that action.

Whether the statue stays at the bottom of the harbour or is fished out, or whatever you do with a slave-trading monument when it gets what it deserves, I hope that we know that like the statue, we cannot come back from this. That Bristol, a city so rich with Black culture and history, has made a re-commitment to the work of Black activism. That it has said it will stand with us, centre, listen to us and tear down everything that has been stopping us from thriving. That by cheering in that video, by sharing it in a celebration of our Bristolian pride, we are now bound in a contract to go beyond just loving Black music, or coming to carnival, or being glad that we freshen up the party.

Instead, Bristolians are now in a pact to tear down the racist statues, change the awful street names, support the protestors if they are persecuted and help us claim space in a city that owes us so much.

Black Lives Matter Bristol have set up a crowdfunder to pay for the legal cost of the protestors.