Inside Spain’s Afro-Spaniard and QTPOC scene where migrant sounds meet community

After a pandemic-induced pause, Spanish clubbers want to find spaces to dance and connect with their people. We met rising stars joining the dots between identity and revelry.

Kemi Alemoru

09 Mar 2022

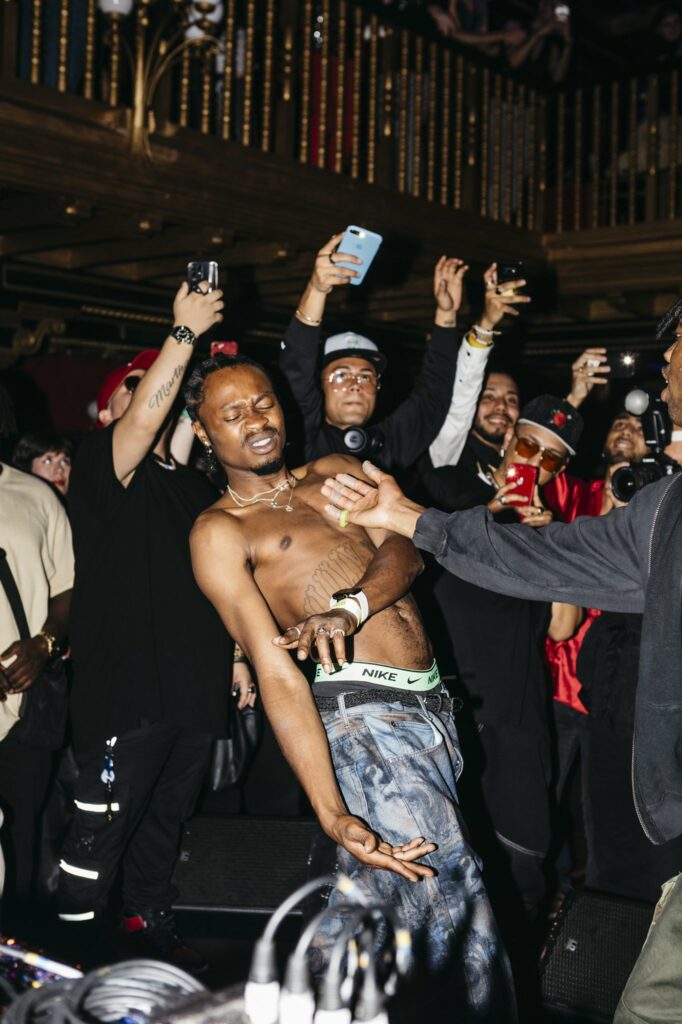

Courtesy of Ballantine's

All eyes look upwards as the crowd collectively holds their breath on the dancefloor of the neon-lit ballroom. Our hosts for the evening, Snap Bitch! a QTPOC-centred ballroom collective, have spent the last couple of hours schooling the room on the basics of Voguing. A couple dozen people have learned spins and dips, werking their hands and crawling along the wooden floor, then sliding their knees in, before popping their bums into the air for a ‘sexy’ finish. As the students are encouraged to demonstrate their new skills, Cacao Laveaux, a local dancer, takes her position on the balcony above. Now, as we stare, Cacao swings her long limbs over to pose and hangs on the ledge, before dropping to the dancefloor below. She lands in a death drop and twirls. Then another death drop – this time she rips her bra off to finish topless. “It’s raining femme,” laughs Queen Bitch, a member of Snap Bitch! with impeccable comic timing.

Spain is experiencing a nightlife renaissance. This event, along with others on the True Music Studios festival line-up during the last fortnight in January, was intended to shine a spotlight on emerging sounds and communities in the country’s nightlife. Some of the brightest names in the scene converged in Madrid for the celebrations, curated by reggaeton DJ Ms Nina and organised by Boiler Room and Ballantine‘s. Landing in beautiful cities like Madrid and Barcelona (as Brits often do), you can easily find culture, good food and stunning architecture that makes you question why we live on plague island. But, as a person of colour, it can be near impossible to know where to go in order to find your people in these places. Yet, out of the embers of a rocky few years, a new scene is rising. One where marginalised communities are taking up space, creating events and forging powerful bonds. I travelled to Madrid to see how collectives, DJs and party-goers were gathering together after a prolonged pandemic-induced hiatus.

Dancefloors across the country are filling with revellers eager for blended sounds. Dubbed ‘Spanish New Wave’, the movement is influenced by genres migrating from South America and Africa, mixing with club sounds traditionally enjoyed by the sunny Southern Europe hotspot. True Music Studio’s lineup included rising stars from the Spanish rap scene like Angolan-Chilean headliner, autotuned agent of chaos Polimá Westcoast, and the fierce hard-hitting LGBTQI+ lyricism of Polemik, who is garnering attention by blending trap and perreo, a dance music genre that emerged in 1980s Puerto Rico.

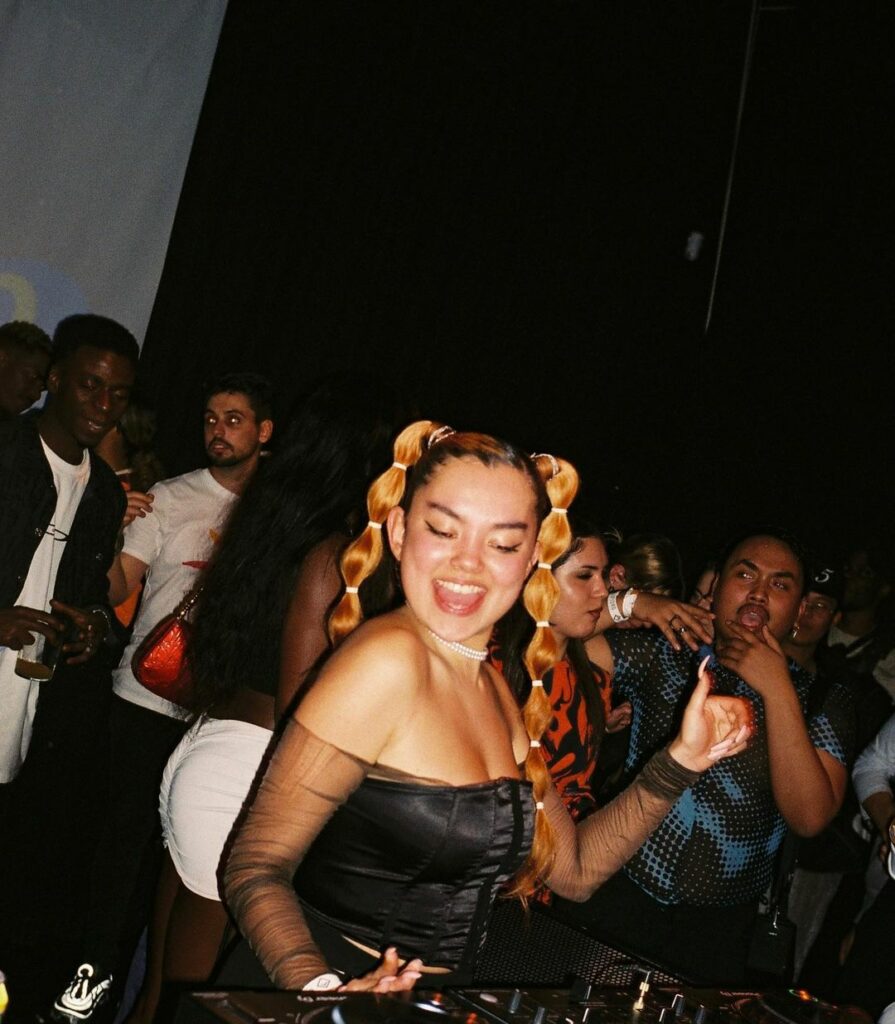

Crowds also sweated to the sounds of Drea, a local DJ and regular at Antidoto club, one of the city’s coolest spots, hosting ‘urban’ nights every Thursday. Her sets blend Brazilian funk, amapiano, kuduro, salsa and “anything with loud beats” as she wants to mix underground sounds with musical styles that belong to minorities that haven’t traditionally been allowed to take up space or get the reach they deserve. It has taken her a while to find promoters who value her work rather than wanting to sell her image. “And I speak from a privileged position being a mixed woman. Boiler Room gave more prominence to artists of colour [in this lineup] but clubs are still a bit behind. It’s like a pyramid in which I feel that black women are the last ones,” she adds. On a more positive note, Drea does say that after the pandemic she’s seen that clubs are slowly betting on people they weren’t before which is “reeducating the public”.

She shouts out others in the scene who are approaching nightlife “passionately and soulfully” to create safer spaces for people of colour without hate. Especially as the country falls in love with African genres. “Voodoo club in Barcelona is a great example of this initiative,” she adds.

I met the co-founder of Voodoo on the dancefloor during the second week of the festival. He was wearing a luminous yellow balaclava with two Shrek-like ears on top and a continuous, contagious smile. After bonding about our rhyming names (I am Kemi and he is Yemi) he told me about his “crazy parties”. A week before I arrived they had brought their resident artists like Brisa Nunjo and DJs like Naguiyami and Slimboy Flacko and I’d been told by several people that it was one of the highlights of the entire program. When we caught up on Zoom later he joined with his business partner and fashion designer Wekaforé Maniu Jibril (who also has a penchant for off-piste headwear as demonstrated by a colourful crochet hat). They described how Voodoo had become a night that has attracted politically aware, community focussed, music lovers.

“They didn’t like the look of us so we had to spend the night outside around Barcelona on a cold night stranded”

The pair had initially bonded over their similarities in a country where they had struggled to find many people like themselves. Both were born in Lagos. Yemi Alaran moved to Spain when he was 14 and Wekaforé arrived at 20, setting up home in Bilbao, in the north of the country. He remembers his first clubbing experience in Barcelona – he’d taken the two hour trip with some friends in search of a good night out and was turned away at the door. “They didn’t like the look of us so we had to spend the night outside around Barcelona on a cold night stranded,” he says. “[In other Spanish clubs] I’ve had distress of [white] people calling me a ‘nigger’ trying to be on some American shit.” For a while he’d stopped listening to hip hop to get back in touch with his African roots, he laughs.

Despite the drama in Barcelona, Wekaforé was still keen to live somewhere lively and started doing more research as to what else the city had to offer which is when he found an article in i-D magazine about “cool kids” in the city which featured Yemi. “I was amazed there was a black guy in Barcelona who was Nigerian so I hit him up on social media and told him I wanted to come and build a community and create employment blah blah,” he says. Yemi says it was the perfect connection. “I’d been looking for someone to help push the vision, finding people to surround myself with who have the same goals.”

Now they’re catering to young Black Spaniards who want to hear Afrobeats, amapiano, angolan house, alté and azonto. After three years they not only have a club night which frequently sells out, but also a music label, talent agency, and dance collective under the Voodoo brand name. They’ve even launched their own Voodoo Carnival at Parc del Forum, which was Spain’s first Afrobeats festival. It was held at the same site as Primavera Sound, for whom Yemi also hosts a monthly Voodoo radio show. Sticking to their mission of connecting Spain with their home continent they’ve also been strengthening their links with other diaspora dances like the UK-Nigerian punk fashion collective Vivendii Sound. “We keep in touch with our counterparts in Lagos. We’ve tried to bring Santi, Odunsi and all those guys, but there have been problems with visas, that’s the biggest barrier.”

Yemi says the shifting focus towards bringing partygoers of colour together is growing. “In three years we’ll be in a better position and things like Voodoo club will inspire the rest. If we can do this shit they can do it as well,” he adds.

“If we are together then we can just enjoy ourselves because we no longer have problems at that moment. We are a community, we are connected.”

This DIY contagion was a major factor in the creation of Snap Bitch! The collective was just getting started in 2019 before venue closures around Madrid. Their mission was to support and cultivate a QTPOC community as Galaxia LaPerla, “the mother”, asserts “there wasn’t one”. Reaching out to each of the team individually on social media, they eventually met up to discuss becoming a collective and found a life-affirming friendship. “For me it’s like family,” says Queen Bitch. A breakthrough moment came in the form of Noche Blanca, or the White Night arts festival where they were called upon to platform the social roots of ballroom, and demonstrate community and resistance. As a mostly migrant and majority gender-nonconforming troupe they are one of the few collectives in Spain honouring the art form’s original roots by centring on people of colour. “The people who created this culture,” adds Galaxia.

Speaking to them in a cramped back room of the club their excitement is palpable. Each of them introduces themselves by unpacking the meaning of their ballroom names. Queen Bitch is only 18-years-old. After a childhood of bouncing between four boarding schools, she made her first friend two years ago who gave her the riotous name. Diwata takes their name from the Filipinx word for ‘fairy’. Honouring their roots in their mononym counteracts the culture shock and shame they felt when they moved to Spain at 14. Tolu’s name comes from their hometown in Columbia. Riri, who speaks to me via a translator, loved Rihanna’s Loud album as it got them through difficult times in high school. “People were looking at me like I would never succeed so that name empowered me,” they explain. Whereas, Galaxia Laperla’s name pays homage to their Peruvian hometown it also is an ode to the art of Voguing as it nods to the House of La Perla, home of ballroom legend Daesja. “New names make us feel more empowered,” she says.

Before establishing this night, the group say they were bored of “cringe” club offerings with white gay attendees. When asked about their experiences in those spaces there’s a long silence while the question is relayed to Riri; “Messy,” they reply in an exaggerated English accent, before laughing. The existence of racism in queer spaces is often denied, but as people of colour, they didn’t feel validated, protected or respected. While nights with other people of colour are emerging, they’re still marginalised by their sexuality and gender identities within those spaces too. But when there’s a room full of people with similar experiences the energy is intoxicating. “They can relate, they have the same problems so we don’t have to tell each other. If we are together then we can just enjoy ourselves because we no longer have problems at that moment. We are a community, we are connected,” Queen Bitch says, balling her fists.

In service to this community, they use the money to book taxis home for people or fund materials for others to get into performing. “What ballroom gives to us we try to give back,” says Tolu. And there are others making room too. Queen Bitch is starting her own migrant kiki ball. “I’ll be the youngest person to do it with everyone POC,” she says before being interrupted by a gasp from Galaxia. “I said at my age bitch! Anyway, I’ll be doing discounts for people of colour only. White people call me racist for that.”

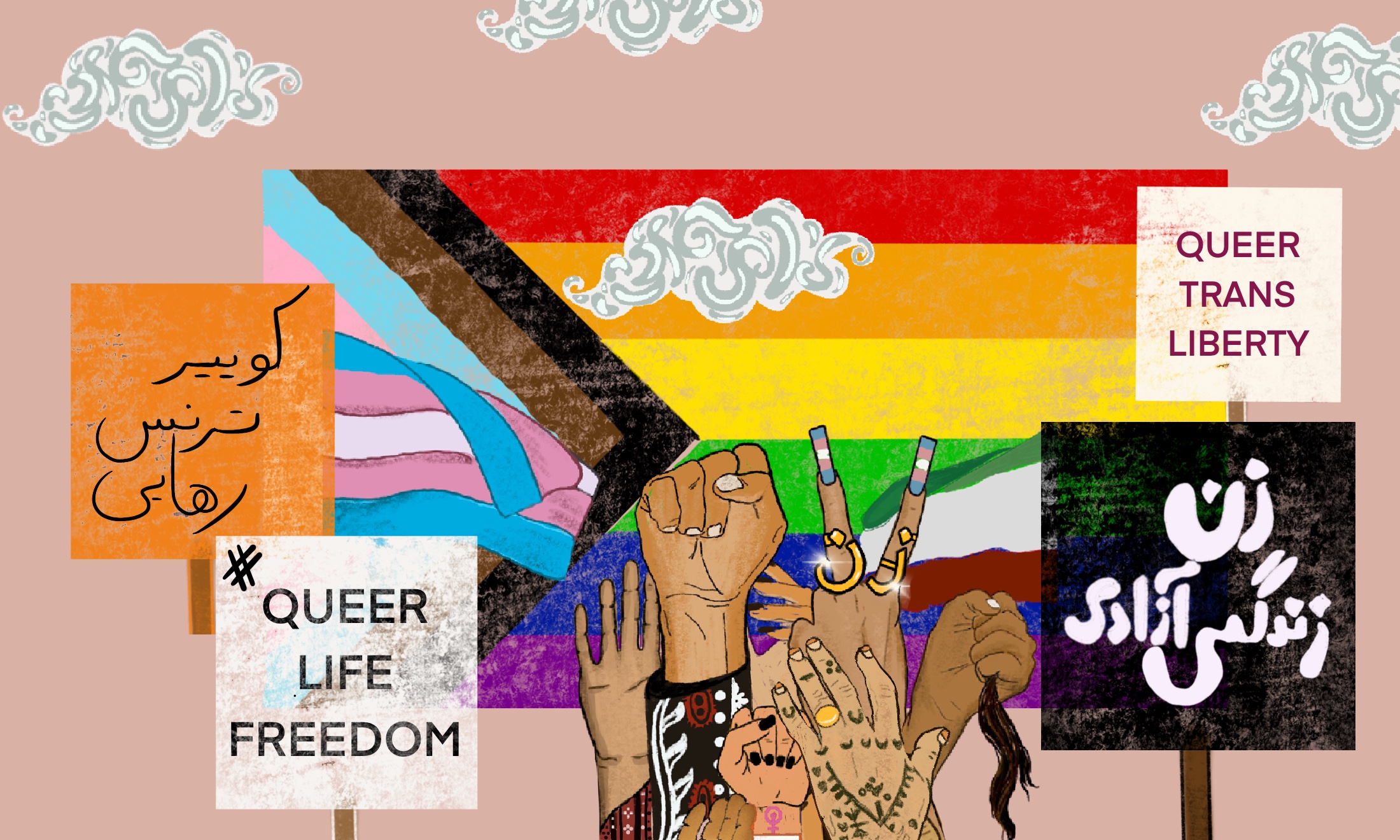

But there are more popping up across the country. Like the Kiki House of Laveaux, a dance troupe that started in France, which has a new Spanish contingent, that honours the ancestors of people of colour; Clapback Barcelona, a club night for QTPOC, as well as Don’t Hit La Negrx. The latter is a “party of the bitches, migrants, and trans women” named after a salsa song by Joe Arroyo about anti-African violence towards black women in 17th century Cartagena. The events are hosted in squatted buildings and private clubs. The organiser tells me over Instagram that the pandemic has shone a light on oppression. “Our fragility (especially trans-fragility) has become more recognised. People are more empathetic but transphobia and racism still exist,” they write. The music during the night is used to spotlight local QTPOC artists and DJs. “We try to make our sets coexist with different rhythms that have to do with our diverse origins and that connect us with our roots… also trending music that makes us vibrate.”

On a series of cold nights, young Spaniards exude warmth rushing over to each other hugging and giggling in the queue at the doors of the red-lit Boiler Room venue, the bassline from inside punctuating their excited speech. Their moods are lifted at the thought of dancing together again after a pandemic-induced hiatus. But the sounds have shifted, and the politics of the last few years means people want more inclusive spaces. Communities that have collectively reckoned with their identity-based traumas at the tumultuous turn of the decade are channelling their energy towards creating spaces for their joy.

Like what you’re reading? Our groundbreaking journalism relies on the crucial support of a community of gal-dem members. We would not be able to continue to hold truth to power in this industry without them, and you can support us from £5 per month – less than a weekly coffee.

Against the binary: finding home in my intergenerational queer family

‘The day Ghana’s anti-LGBTQI+ bill is passed, I will be in jail’

LGBTQI+ people are at the forefront of Iran’s revolution