Meet the people changing what it means to be a family

People who have been excluded from the textbook definitions of family are making their own models.

June Bellebono

30 Sep 2022

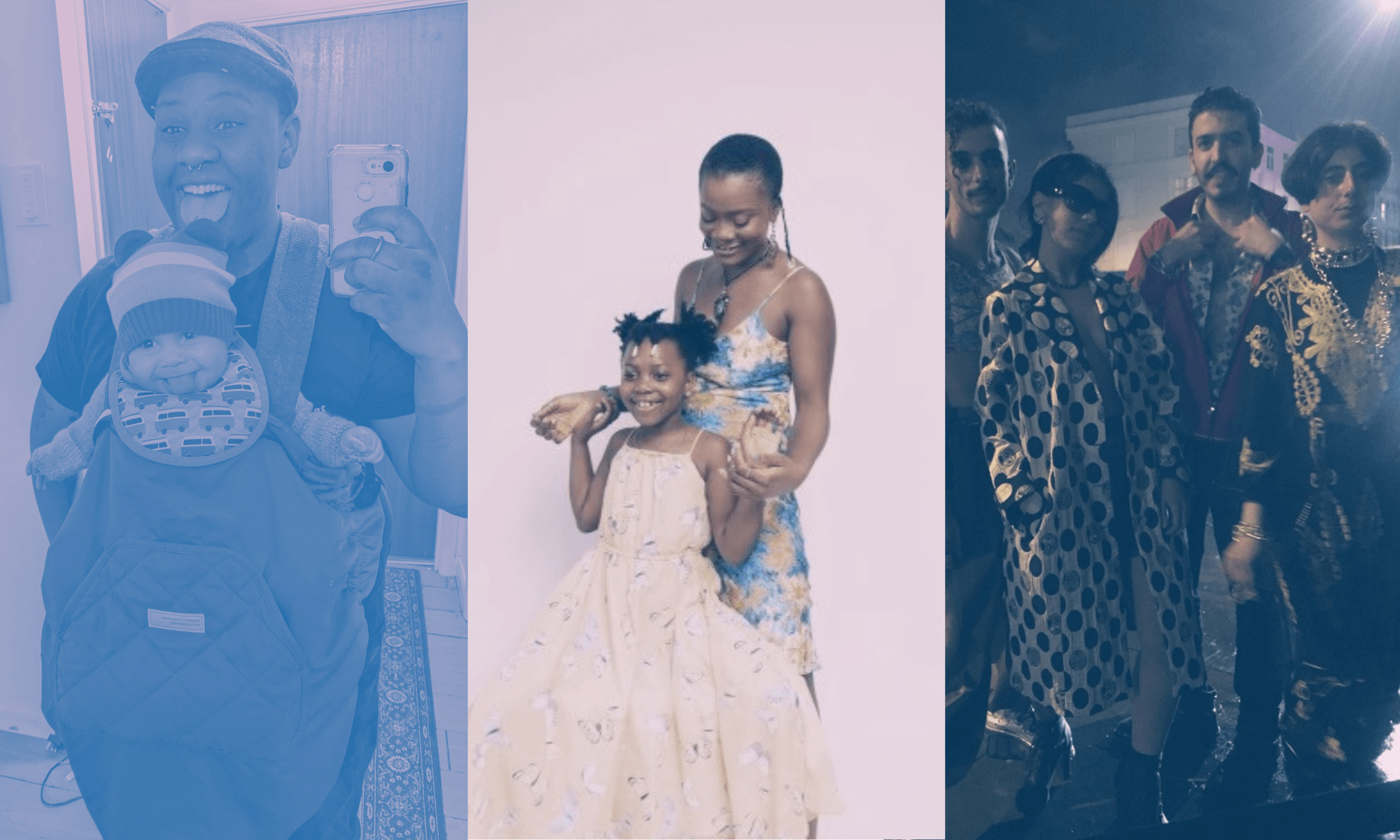

courtesy of CJ Rivers, Tobi Adebajo and Golcher of POA

It’s 2am in north London, and my friends Asma, Maryan and I are a bit waved and chatting in the kitchen. The conversation drifts towards our vision for our futures, and how and with whom we see ourselves growing older. We’re not thinking about the housing crisis or the recession. We’re allowing ourselves to indulge in our most ambitious dreams.

We’re envisioning a future where we’ll all be neighbours and can knock on each other’s doors – not only to borrow oat milk or toilet paper but to look after each other and our little ones. It’s a vision that includes a beautiful queer co-operative where we can channel all of our inner lesbianism to survive and thrive.

I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve had this conversation over the years, with different friends and in slightly different versions. But the crux of it is always the same: our futures, our families, our styles of parenting, are nothing like the realities we experienced when growing up. Instead of creating a culture where elder members can do no wrong, we’d strive to create one where age doesn’t come with authority. Instead of subjecting children to judgement and shame in the way we were, we’d ensure unadulterated joy is ultimately the goal. Instead of failure being seen as something to dread, we’d welcome it as a source of growth.

The tone is always dreamy, but with an underlying sadness. The obstacle of capitalism feels a bit too unsurpassable for our queer co-operative fantasy to come true. Most of the time, we’ll end the conversation by giving each other a tight hug and a loud “awww” and never talk about it again.

“Our futures, our families, our styles of parenting, are nothing like the realities we experienced when growing up”

Traditional understandings of family – where blood and biology reign supreme – inherently create the conditions for inequality. Historically, in the dynamic of the nuclear family, wives and mothers have taken on unpaid caretaking roles, creating a cycle where they were left out of possibilities of work (and thus financial independence), and producing the conditions where domestic abuse could prosper unchecked.

Now, with the normalisation of both parents in the household holding employment, the burden has shifted from the biological mother to other women who are seen as less worthy. Typically this is migrant women with precarious citizenship status who are hired as domestic workers, often find themselves exploited – both financially and socially – and are expected to take on the tasks that biological parents no longer want to do.

Whether because of queerness, race, disability, poverty or any other characteristic where your life is made harder by our capitalist society, challenging traditional understandings of family needs to be a fundamental element in fighting for collective liberation. Fortunately, there’s an abundance of references we can lean into to create the sustainable “families” we want for ourselves.

“Challenging traditional understandings of family needs to be a fundamental element in fighting for our collective liberation. Fortunately, there’s an abundance of references we can lean into”

Simply by looking outside the confines of British society, we are able to witness representations which surpass the nucleus, which are intergenerational and extended, and where family ownership and responsibility aren’t placed on a few. In the Burmese households I visited throughout my childhood, I’d see grandparents and grandchildren living together more often than not, and aunties and uncles also being an integral part of the family. There seemed to be a mutual sense of unspoken unconditional reliance where the act of care is approached with joy, not resentment.

“Auntiness” in itself was never something I attached to biology. In fact, a lot of the aunties who have brought me up and fed me don’t actually share a single gene with me. They’re family friends whose bond was strong enough for my mum to trust them with my upbringing, and they loved me enough to ensure I was taken care of.

An understanding of family outside of Western structures can prove beneficial in seeing a better alternative. However, when you’re queer, biological relatives can time and again fail to provide unconditional love. Historically, these people have had to create their own families who were not assumed but chosen.

“When you’re queer, biological relatives can time and again fail to provide unconditional love”

While LGBTQ+ liberation pioneers Marsha P Johnson and Sylvia Rivera often have their words depoliticised to ensure they’re palatable enough to be put on a T-shirt, a deeper look into their work allows us to truly see the radical alternatives they lived and embodied. When founding Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) in 1970, they signed a lease for a cheap, derelict space, which they repaired and made a home for homeless LGBTQ+ youth. They created a mutual aid-based ecosystem where, through sex work and theft (the only options they were afforded), they were able to survive and create a future with different conditions. The language they used was familiar – terms like “mother” and “children” – but blood held no relevance in these relationships.

Similarly, in ballroom culture, “houses” function as alternative families. Bam Bam, who has been part of the London scene for years and is now the mother of the recently launched Kiki House of Laveaux, takes her/their role as a mother incredibly seriously. “I’ve always felt strongly about having support in a holistic way, possibly as it took me a long time to find it myself, after looking at the wrong people or the club,” they explain.

In some ways, this feeling recalls the one biological parents may promote when wishing for a better, easier life for their kids. However, shared histories and identity make this even more meaningful. “As trans and queer people, it’s vital to have someone who’s walked your path [and] who can point you in the right direction,” says Bam Bam. “Whether that’s healthcare, sex, housing, drugs, shopping, margaritas, how to eat an oyster, sending an invoice, whatever. Most importantly I’m still going to be there, whichever direction you choose, to love and aid you on your own route”.

“Most importantly I’m still going to be there, whichever direction you choose, to love and aid you on your own route”

Bam Bam

Similar sentiments emerge from Golcher, one of the organisers of Pride of Arabia, a social support network for queer people from the Southwest Asian and North African (SWANA) region. She emphasises that the primary difference she’s noticed between her biological family and the one she’s created is that with the former, being her whole self is held against her, whereas the latter encourages spaces of discomfort in aid of growth. “With your chosen family, the darker corners of your identity have also been activated and shown, and you are still cared for and held and loved,” she says.

What stands out from both is that ultimately love is at the core of these families. However, unlike with biological families, this is a love that’s been consensually formed and is rooted in intentionality. Golcher doesn’t shy away from talking about the complexities of doing this work but emphasises that “we all want to do better. We want to be less toxic in the way we love and actually define love in a way that’s a verb rather than a noun.”

South Londoner CJ Rivers has been raising their seven-month-old child Micah (whose gender is yet to be determined) as a single non-binary parent. This was an active, willing choice, rather than an imposed one. “Being a parent is the only job I’ve ever wanted,” they say. “It’s really exciting that I finally get to do it. It’s hard, sure, as any job can be from time to time, but it’s exactly what I signed up for and I’m loving every second of it.”

“It’s exactly what I signed up for and I’m loving every second of it”

CJ Rivers

CJ’s words sit in direct contrast with the view of single parenthood that we’re presented within the traditional familial paradigm: one that’s less than ideal, unfortunate, lonely. When I ask CJ about their biggest joy in parenting Micah, loneliness is the last thing that transpires. “One of the biggest joys for me has been seeing how people in my life interact with Micah and vice versa,” they say. “One of the first moments of pure joy I felt after giving birth wasn’t being able to hold Micah in my arms – it was the moment I handed them over to my birth partner and watched him hold them close. There’s something about seeing the people you love and care about loving and caring about your kid, wholly and unconditionally, that is absolute magic.”

Similarly, London-based unbinary queer artist and doula Tobi Adebajo shares with me that their community is what allows them to be able to parent their eight-year-old child, Gabi, in the way that they do. Having folks around them who are committed to Gabi’s happiness encourages an environment where “we’re all learning together and creating wonderful futures”. Tobi’s approach to parenting is one that respects their child’s autonomy over anything else, and it’s hard not to see this as the optimal approach when they tell me how special it is to witness “the magnificence of a child who is really able to advocate for themselves, who has amazing emotional language and also teaches me so much every day just by being”.

Recently, the people of Cuba voted overwhelmingly in favour of legal reform that recognises multiple family structures. Marriage and adoption rights will be extended to queer people, surrogacy will become legal, and the rights of children and grandparents will be redefined. Cuba’s new “family code” is evidence that progress is being made, but also highlights the obstacles that come with creating alternative family structures when legal systems don’t provide appropriate recognition. A hidden piece of queer history is the practice of gay adult adoption, where American queer couples in the 1970s and 1980s would adopt one another as it was their only way to be legally bound and therefore receive the same rights and support that heterosexual people were granted.

“Cuba’s new ‘family code’ is evidence that progress is being made, but also highlights the obstacles that come with creating alternative family structures”

CJ recounts the pain that has come from being forced to misgender and mislabel themselves in Micah’s documents and the hardships that have emerged from a system which offers inadequate financial support to parents, especially those who are single. It’s difficult not to see these obstacles as part of a larger scheme that aims to block our liberation to ensure a system of inequality is maintained.

But there’s strength in its challenge. “Society is such a mess right now,” says Tobi. “We shouldn’t even be trying to use the old models as templates to look after anything. We are forging new paths. We are opening up space for different types of language.”

Utopias are not unachievable. At some point, all of these stories were imagined and could have been deemed impossible – just like the queer co-operative my friends and I drunkenly dreamed of that night. But, through an unapologetic drive towards collective joy, they ultimately became reality.

This article is from our 2022 print issue, UTOPIA / DYSTOPIA – order your copy here!

Like what you’re reading? Our groundbreaking journalism relies on the crucial support of a community of gal-dem members. We would not be able to continue to hold truth to power in this industry without them, and you can support us from £5 per month – less than a weekly coffee.

Our members get exclusive access to events, discounts from independent brands, newsletters from our editors, quarterly gifts, print magazines, and so much more!

Against the binary: finding home in my intergenerational queer family

Wanderthirst: returning to Malaysia and my family, I remembered what unconditional love feels like

Swipe Left: How I’m learning to date while under pressure from my family to marry