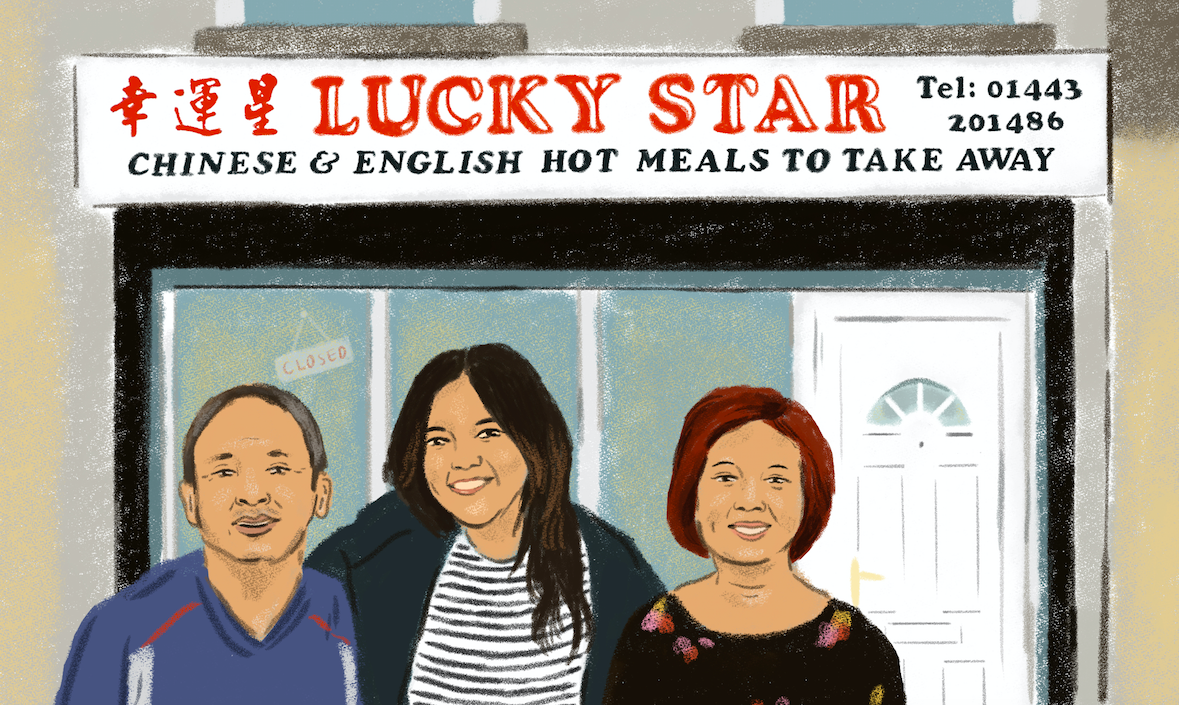

A joyful celebration of Britain’s Chinese takeaways

With Chinese restaurants quickly becoming a target for attacks, Angela Hui’s new project aims to bring light to the people and stories from inside Britain’s beloved takeouts.

Angela Hui

24 Mar 2021

Illustration by Javie Huxley

In a time where we’re heavily reliant on takeaways and deliveries thanks to the pandemic, we know almost next to nothing about what goes on behind closed doors inside some of our favourite takeaways.

One of the nation’s most loved is the Chinese takeaway. It’s been such an integral part of British culture, and it was one of the first lines of work my parents got into when they migrated over from Hong Kong and China to the UK in 1985. They had very little money, no understanding of English and only a promise of a better future. There was little choice when it came to career and job satisfaction then – it didn’t exist for marginalised people in predominantly white societies. As with many overseas Chinese takeaway families, my parents stayed humble, quietly assimilated and dealt with whatever life in the UK threw at them.

Since the start of the outbreak of Covid-19, the past year has been filled with hatred towards the East and South East Asian (ESEA) community, with UK police data showing that Covid-related anti-Asian hate crimes rose by 300%. This also meant that ESEA-owned businesses and Chinese takeaways quickly became a red bull’s eye target for attacks.

“The goal of the first generation of Chinese immigrants was to survive”

Last year, a takeaway owner in Hitchin was spat at in the face by a teenager and a Dudley-based Chinese takeaway was vandalised with abusive racist messages. Earlier this month, a 16-year-old girl, Wenjing Ling, was murdered in her family’s Chinese takeaway in South Wales near where I grew up. It’s not just Chinese takeaways that have to bear the brunt of these senseless attacks. Chinatowns suffered from vandalism and plummeting business as sensationalist headlines meant bigots leapt to the unproven conclusion that anything Chinese-related or Chinese-looking meant Coronavirus.

In response, I set up the Chinese Takeaways UK Instagram account. An idea I had been floating around after my parents sold our beloved Chinese takeaway in 2018. I began to reflect on my childhood working in the kitchen. What initially started as a tweet about a photo feature, developed and grew into a digital journal documenting all the Chinese takeaways up and down the country. I wanted to highlight and share the gruelling lives of the unseen workers in the hospitality industry – albeit the cottage industry of the immigrant family restaurants and takeaways. It’s a closer look into the lives of people who run these businesses and to tell the unheard stories of the families who often live above the shops.

Photography via Chinese Takeaways UK

Chinese immigrants introduced many new flavours to the nation when they first began to come to the UK in the early 19th century, one being Chinese takeaways. London got its very first taste of Chinese food in 1884 at the International Health Exhibition in South Kensington and Brits have shared a love for Chinese food ever since. Over the years, the Chinese takeaway became an institution across the UK, where there is one in every rural town situated in uniformly white communities where soy sauce is still considered exotic. They tend to be spread out or in the next village over to avoid direct competition with other takeaways, which is why the ESEA community here in the UK feels so dispersed and isolated compared to big cities and communities in North America.

Chinese families took over former fish and chip shops, which created Chinese takeaway-chippy hybrids. Soon, deep-fried items became a mainstay on menus such as battered sausages, chicken balls, fish cakes, prawn toast, spring rolls and chips – often with curry sauce (or gravy, depending on where in the UK you are), rice and noodles all in one convenient silver foil container.

“I will be forever grateful to New Dragon Town and my parents. The shop allowed my family to survive”

Anna Chan

The goal of the first generation of Chinese immigrants was to survive. Most of them had at best high school-level education (my mother only finished primary school) and weren’t the privileged type of immigrants. At that time, Chinese ingredients weren’t as available as they are now, so they couldn’t display the full extent of gastronomy and adapted to local palates in order to survive. The food on offer was far removed from what my family and I typically ate for our family meal before service – whole steamed sea bass, healing bone broths, salted egg, kai lan choi (Chinese broccoli) with oyster sauce, lap cheong (Chinese sausage) and steamed spare ribs with fermented black beans and boiled white rice. Anglo-Cantonese food is loosely based on traditional Cantonese cooking and this simplified, watered-down western version is what Brits have come to know and love. Despite its “inauthenticity” it proved to be a huge success for over two decades.

However, in the age of Deliveroo, Just Eat and Uber Eats, a plethora of culinary choices are now readily available from a tap of a button in the palm of your hand. Now, the number of Chinese takeaways are on the decline and are getting left behind due to being cash-only, lack of digitisation and a change in people’s eating habits.

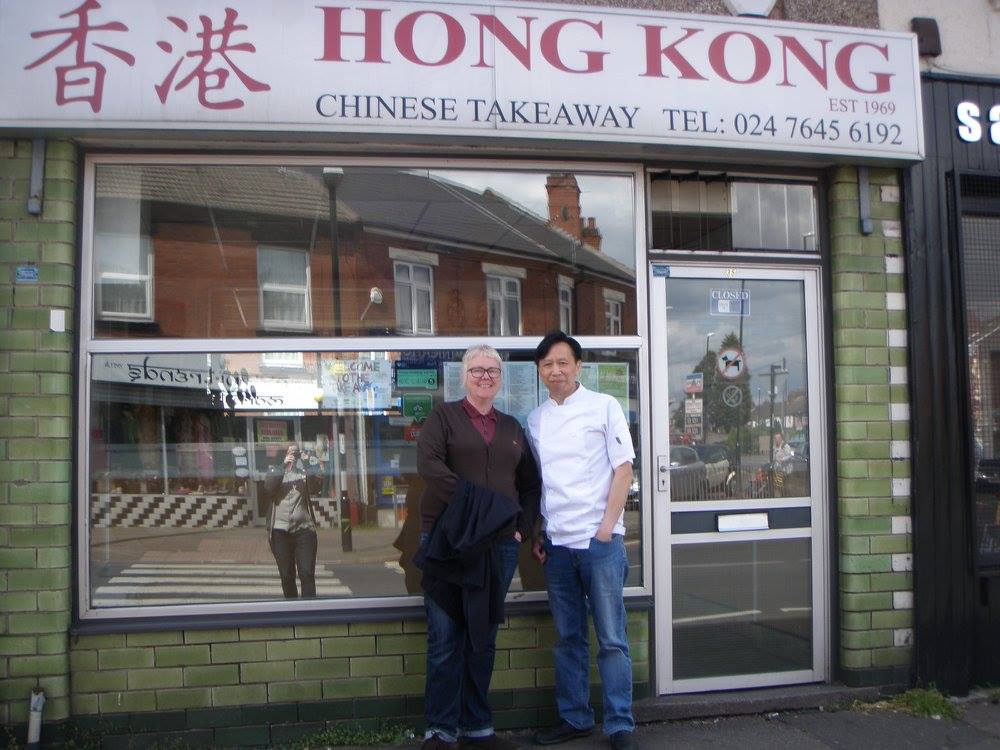

British-born Steve Cheung, owner of Hong Kong Takeaway in Coventry started working in the family business when he was 16 years old and the takeaway life is all he knows. “We are an old school takeaway. We haven’t adapted to the modern ways and there’s just me, another chef and a driver I call whenever there is a delivery,” he explains. “I find it difficult to find staff that I can communicate with as they are mostly from China and they command high wages.”

Photography via Chinese Takeaways UK

Cheung lived above the shop and would see everything first-hand as a child. He chipped in helping his parents when they owned the shop back in the 1950s and learnt how to cook there too. “Eventually, work was a bit tedious and you’d get bored and lazy,” he laughs. “We’d peel prawns and chop potatoes by hand and it became very boring as well, but it had to be done because that’s what paid the bills and gave a roof over our heads.”

For Jennifer Lo, based in Staffordshire, working at the takeaway alongside her parents was also her first job and last job before she went to university. “I used to help bag prawn crackers when I was around 12 years old, then it moved on to peeling prawns, quartering mushrooms, beating eggs and prepping sesame prawn toasts,” she reminisces. “When I was old enough, I worked in the kitchen and helped out in the front taking orders.”

Her family’s takeaway business has been serving British Chinese dishes for the last 38 years. Westernised Chinese dishes feature on the menu such as chow mein, fried rice, black bean, satay and sweet and sour dishes. Lo’s dad’s curry sauce recipe is so popular amongst the locals that regulars often order the ‘Alan special’. A dish named after a loyal customer which consists of egg fried rice, chips, slices of chicken and curry sauce.

“Apparently our family cat, Kizzy, was bought for £5 and an extra pot of curry sauce when my dad was doing deliveries to a customer’s house”

Jennifer Lo

“Apparently our family cat, Kizzy, was bought for £5 and an extra pot of curry sauce when my dad was doing deliveries to a customer’s house,” she laughs. “This was back some time in the 90s when I was a kid and my sister and I really wanted a cat. It’s crazy to think pets could be bought for a fiver and in exchange for a pot of curry sauce.”

Most takeaways have a loyal following, but they don’t accept cards, have any online presence, or even a menu widely available anywhere. Survival comes through good old fashioned word of mouth, which has kept regulars and locals fed for many years. Anna Chan’s family takeaway in coastal seaside town Morecambe, New Dragon Town, has been going for over 30 years and is the go-to place after a Shrimps football match.

“Most businesses were impacted as people didn’t want to go outside and my parents have never delivered as it was too much hassle,” Chan explains. “They have their regular customers who come to order, many have been supportive and understanding of the new Covid-19 compliant layout we have in the shop.”

Photography via Chinese Takeaways UK

While business has slowed down in recent years with competition from other takeaways opening up and more options available, Chan’s parents are getting by with those who do visit.

“My parents have been in the community for a long, long time, they haven’t experienced any more or any less anti-Asian sentiments. Although, I do worry that they would not tell me if they had, as not to burden the family with these things,” she says. “I will be forever grateful to New Dragon Town and my parents. The shop allowed my family to survive and gave me many opportunities that my own parents’ and generations of my Chinese lineage could not afford.”

Some say the future of traditional Chinese takeaways is dead, with parents like mine making a conscious decision to not want or ask their children to carry on with the family business because of the labour-intensive nature of work. We’re currently going through a rebranding and gentrification of Chinese restaurants and there will always be new iterations of what Chinese food is and what it means for people.

Across the UK’s Chinese food outlets, it’s now possible to feast on hand-pulled belt noodles from Xi’an, pan-fried baozi from Shanghai and fiery hot pots from Sichuan. Traditional Anglo-Cantonese fare once cornered the market in the UK and will have its loyal following, but in order for takeaways to survive, they need to modernise and cater for the younger, affluent generation or they may get left behind. And that’s precisely why I started this project: to celebrate and uplift these traditional independent businesses and help give them a fighting chance.