Image credit: Canva

We need to talk about the anti-racism genre

As publishers rush to commission more anti-racist books, are they capitalising on oppression?

Mishti Ali

23 Dec 2020

Anti-racism has been a hot topic for commentators and activists alike in 2020. Alongside the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, there has been exponential growth in the availability of anti-racist literature. These works promise to teach readers how to understand racism, both in an academic sense and through discussion of authors’ personal experiences. But as the anti-racist titles stack up, a quiet discomfort is growing around the way they’re packaged and the narratives they espouse.

I was initially overjoyed by these books. These were my experiences, our experiences, being verbalised in a way I’d never been exposed to before. Finally, there were answers to the questions which have defined my reality, answers which weren’t provided at school. My understanding of racism had been limited to a brief unit on slavery at school and annual Black History Month assemblies. There is no denying that education around anti-racism, through literature or otherwise, is categorically a ‘good thing’ – however, that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be open to thoughtful critique.

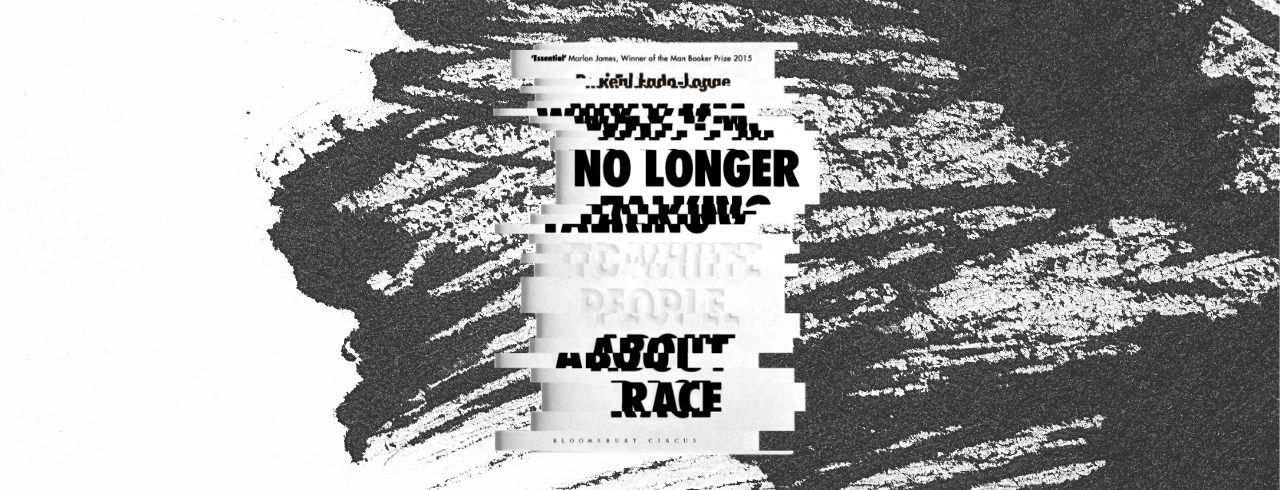

The blueprint for the ‘anti-racist textbook’ is Reni Eddo-Lodge’s 2017 debut, Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race. The book – based on an 2014 essay posted on Reni’s blog – has become distinctive for its bold typeface, monochromatic design, and frank title. In fact, this bluntness was what garnered a lot of initial attention, much of it controversial.

But slowly Reni’s no-holds-barred approach, coupled with the thoughtful, accessible argument she laid out, made her a publishing star and the book became a phenomenon. Reni became the first Black British author to top the UK publishing charts in 2020, during a summer of anti-racism protests. For publishing house Bloomsbury, Why I’m No Longer Talking has proved an investment that more than delivered. So it’s not surprising that in the years which have followed, there’s been a spate of similar-looking titles in the bookshop.

The aesthetics of anti-racist literature

In 2018, Kalwant Bhopal’s White Privilege: The Myth of a Post-Racial Society was published, followed by Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility in 2019, and Layla Saad’s Me and White Supremacy. Ben Lindsay’s We Need to Talk About Race, published in 2019, was even criticised for its similarity to Reni’s work, with a cover which looked as though it had been lifted directly from hers, despite the contents of the book being very different. That the marketing team for We Need to Talk About Race sought to follow the exact playbook which culminated in Reni’s success, demonstrates that many publishing houses know exactly what they’re doing when releasing book after book with similar covers.

Looking at the design of some of the most high-profile anti-racist titles side by side, you’d be forgiven for any confusion. With whiteness prominent (literally, usually in block capitals), often combined with a bold, sans serif typeface reminiscent of Reni’s book, as well as a minimalistic colour palette, these books bear more than a passing resemblance to each other. Otegha Uwagba’s Whites: On Race and Other Falsehoods, Sophie Williams’ Anti-Racist Ally, Frederick Joseph’s The Black Friend: On Being a Better White Person and Emma Dabiri’s What White People Can Do Next are the latest releases in the anti-racism category with covers that fall into this trope.

“Looking at the design of some of the most high-profile anti-racist titles side by side, you’d be forgiven for any confusion”

But the problem extends beyond the aesthetic. “The publishing industry has most certainly ripped off ideas from Black authors and encouraged other Black authors to regurgitate them,” says Yomi Adegoke, journalist and author of Slay In Your Lane. “But because both groups are black, there rarely is as much [uproar],” she continues. “Speaking from personal experience it’s definitely happened with Slay In Your Lane where it’s been like, ‘here’s this book, it’s done well, we’re going to regurgitate this idea’. That’s definitely what’s been happening in terms of anti-racist guides.”

Yomi notes that there have only been a handful of very visibly successful Black British books over the years, which have been repeated because the industry is “trend-led” and that she thinks there’s a “pressure to prove viability” with Black books. She doesn’t believe the want or desire to copy these books comes from individual writers, but rather that it’s a calculated commercial decision. This could in part be led by the reliance on “comparison titles”; markers that the industry uses to judge the potential success of a book and demonstrate who it may appeal to.

“There has been an issue with finding comp titles for books (mainly non-fiction) for black and even writers of colour due to the lack of books being published by the big publishing houses,” says one publisher who’s chosen to remain anonymous. “So when we do see books such as Slay in Your Lane or What a Time to be Alone sell incredibly well there’s a slight frenzy to publish similar books or authors as [publishers] can finally see the readership – so they start finding similar authors or books to acquire.”

The publisher adds: “Even stranger might be seeing these two books being used as comparison titles in the acquisition stage when the only similarity might be the writer is a Black woman. If the proposed book is acquired then the marketing, publicity and packaging might look similar so they can try to sell to the same readership when the author might have been better served being compared to a non-black writer in the same field.”

“When it comes to anti-racist texts, many of the books’ covers and marketing strategies seem to do them a disservice”

Even so, when it comes to anti-racist texts, many of the books’ titles, covers and marketing strategies seem to do them a disservice, particularly when the writers themselves place such weight on nuance. What White People Can Do Next (set for release in March 2021), for instance, has floral cross stitching designs on its cover. The romanticised marketing feels at odds with the harsh reality of everyday racism, especially when both the online resource that inspired the book and Emma Dabiri’s previous book, Don’t Touch My Hair, are rigorously academic.

The contents of the anti-racism genre tend to be incredibly self-aware. In Whites, Otegha herself discusses how flawed a concept the “anti-racism reading list” is, despite inadvertently contributing to it herself through the essay. Layla Saad’s Me and White Supremacy takes the form of a journal, asking questions and forcing the reader to be more introspective. And as a white person writing about race, Robin diAngelo is incredibly critical of both herself and those around her in White Fragility, exploring how whiteness isn’t a rigid construct.

But when aesthetically pleasing covers sell, how do you even choose a cover for the anti-racism genre? Perhaps the answer isn’t clear.

How helpful is the anti-racism genre?

In the wake of the global BLM protests earlier this year, anti-racist literature was hailed as the solution to widespread racism. Millennial pink Instagram infographics, Google Drive links and endless lists of “20 anti-racist books to read” were shared en masse, all pushing readers to titles that might help open their eyes. Yet as with the infographics and links, the texts faded from the public mind rapidly. In June, half of the top 10 bestselling books listed by the likes of Amazon, Barnes and Noble and the New York Times were on anti-racism. The current comparable numbers are far lower. When there’s evidence that some of the books being purchased were never even picked up from stores, it’s clear that sales figures don’t necessarily point to a great deal of progress.

It’s fair to question how far the publishing industry’s anti-racism can go when it stands to benefit so much from people of colour’s sustained suffering. Many of these books began as essays and blog posts, both far more accessible ways of disseminating information, and you have to wonder whether anti-racist resources should even be used to make money. If anti-racism is the intent, surely accessibility should be key? What do the publishers gain from marketing these as full-length non-fiction works?

“It’s fair to question how far the publishing industry’s anti-racism can go when it stands to benefit so much from people of colour’s sustained suffering”

Whether or not these anti-racist efforts are performative will depend on the publishing industry looking inward and changing for the better. Even so, as Constance Grady writes for Vox, “historically, enormous sales of political books have sometimes signified a shift in American culture”. The same could be true of the surge in sales of anti-racist books this summer in both US and the UK. Understood through the framework of “consciousness raising”, anti-racist books can effectively be used to mobilise people and get them actively engaged in work that will lead to systemic change.

To me, however, it feels as though so long as anti-racist literature seeks out white people as its core audience, its goal of distilling racism and its apparatus into a single written piece will be inherently flawed. Racism isn’t a monolith, nor are the experiences of people of colour.

Nesrine Malik, a Guardian columnist and author of We Need New Stories, also thinks we should question the utility of these books. “Who are they for?” she asks. “Do they actually serve the purpose of improving race relations? I suppose it’s too early to tell, but they’re starting to feel rather decorative, like an accessory to someone’s political views, rather than a serious and broad challenge to the status quo.”

Are Black authors being pigeonholed to write about race?

The real fear here is that in continuing to commission non-fiction Black writers almost exclusively around race issues, publishers could be capitalising on oppression. Many of these new anti-racism releases were commissioned and set for publication within a very short timeframe, around when the BLM protests were at their peak. Though topical publishing exists, books are usually given more lead time than a few months. What are the motivations of an industry that’s 90% white and seems to be ignoring the lessons taught by the books they keep churning out at breakneck speed through tokenising their writers?

“Few industries have more power than publishing in determining how we see and understand the world,” says a spokesperson from the Black Writers’ Guild, a new group established to represent the interests of Black authors in the UK. “It’s therefore imperative that the industry responsible for what we read is open, pragmatic and plural.” The Black Writers’ Guild has found that the data shows an underrepresentation of Black authors and decision makers in mainstream publishing. The organisation is now investigating the impact of this on trends, commissions and who publishers consider to be their readership.

“We’re proud of the groundbreaking anti-racist work produced by Black authors in recent years, but there’s a legitimate concern that publishers are overlooking the tastes of Black literary communities and books about Black lives that do not focus on white people or appeal to the sensibilities of white readers,” the Black Writers’ Guild spokesperson adds. “We are also concerned about whether the publishing industry is publishing Black expert voices on a myriad topics beyond race.”

“In continuing to commission non-fiction Black writers almost exclusively around race issues, publishers could be capitalising on oppression”

Nesrine believes it’s broadly a good thing that the publishing industry has started to pay attention to Black writers and their experiences. “The issue arises when Black writers are expected to write purely about race and are then pushed into this pen in the publishing industry where they’re strongly branded and marketed as racism lecturers for the benefit of white people, and will not be allowed to write on other topics that they’re interested because no one is buying those books.”

Her thoughts are echoed by Yomi. “It goes without saying that it’s a great thing that we’re able to build on the pre-existing canon of Black British writing that exists. It’s a positive thing that we’re having conversations about race and racism in an open way that we probably never have in this country before,” she says. “I do however think that there’s a cause for concern that some Black writers are not able to be published or be commissioned unless they’re writing [about] certain subjects.”

Though discussion around race is a positive development, the way publishing houses package and inadvertently homogenise anti-racist literature needs continued examination, as does the practice of commissioning Black authors to write exclusively on race issues. We can continue to support the work of well-researched anti-racist writers, but we shouldn’t take our attention off the publishing industry – they still have a lot of work to do.

Additional reporting by gal-dem staff.