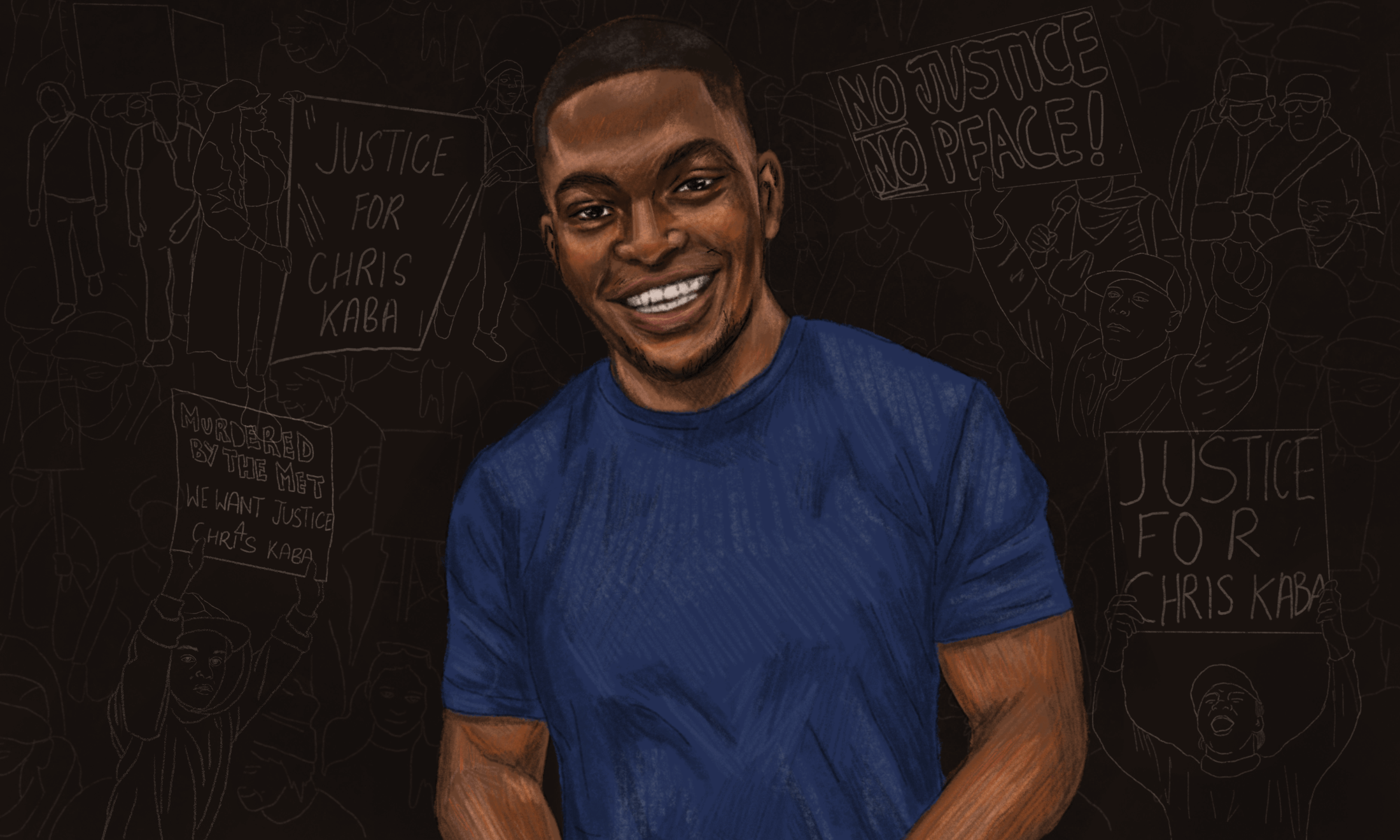

Illustration by Yasmin Ali

Everything you need to know about Black Lives Matter UK

After a summer of protest, questions still remain around the identity of the activist group, how they’re going to spend the million pounds they've raised and why they used an antisemitic trope on Twitter. Here are the answers.

Kimberly McIntosh

25 Sep 2020

It has been a difficult spring and summer season for Black people across the diaspora. The pain and grief is not new. But with national lockdowns acting as an incubator, the conditions were ideal for something that felt different, larger and more urgent. A global pandemic made time static; our individual world’s smaller but our perspectives wider. It was the perfect atmospheric pressure for new allies to hear collective cries for change. At least for a moment, the world listened.

Beyond the performative parade of black squares that temporarily blotted Instagram feeds across continents, a genuine desire to financially support anti-racism work was spurred by the murder of George Floyd and the global Black Lives Matter protests that followed his death.

But the unprecedented level of donations that flowed in led to disquiet over the transparency and mission of some of the recipients. This has been particularly directed at Black Lives Matter UK (UKBLM on Twitter), a coalition of Black activists and organisers across the UK who have raised £1.2 million from over 35,000 donors since they set up a GoFundMe page in June.

In mid-June, Megaman, a founding member of So Solid Crew, called for greater transparency from the group on Twitter, writing: “we need to know the persons who is running this & their names. You shouldn’t hide who you are, you should be as vocal as the rest of them and show a point of contact for credible [people] to reach you for sensible conversations/dialogue.” Later that month, a tweet from the UKBLM account about the Israeli government’s planned annexation of the West Bank was critiqued for leaning into antisemitic tropes by Black Jewish writers.

Ultimately, people have been asking: who are BLM UK, what do they believe and how do they plan to spend all that money?

The origin of Black Lives Matter UK

BLM UK is a coalition of Black activists that came together in 2016 in response to police brutality in the US and the UK. According to an article in Grazia in 2016, it followed “a big anti-racism meeting” of Black activists, many already organising under the BLM banner, following the Brexit referendum result. “Patrisse Cullors [co-founder of Black Lives Matter in the US] came over to the UK to speak to us and we’ve been in constant contact ever since,” a BLM spokesperson tells me on condition of anonymity. BLM UK is still endorsed by Patrisse and BLM US but is not yet an official chapter of the Black Lives Matter Global Network. “It’s something we’re working towards but it’s not a priority at the moment,” they add.

To become an official chapter of BLM US, organisers must be a legal entity, complete an induction process, be in conversations with current chapters and organise with a unique structure that includes shared principles. It is making sure these shared principles translate in the UK context that needs to be negotiated before the process is complete. “An example would be demilitarising the police [which is a BLM US demand],” the spokesperson explains. “Police in the UK do not routinely carry guns.”

Speculation over who the members of BLM UK are has proliferated on social media. There have been claims that they are not all of African or Caribbean descent exacerbated by the anonymity of some of the groups’ members. One Twitter user claimed the group are a “mix and match” of a now-disbanded activist group, the London Black Revolutionaries (or Black Revs). This group organised under the banner of political blackness, meaning people of African and Asian descent mobilised collectively as “Black” people.

“For years BLM UK has been open, holding public meetings. Doing press, doing interviews with people. This has led to attacks from the far right and the press”

A 2016 documentary Generation Revolution followed the London Black Revolutionaries from 2013 as they organised, showing a group of young, earnest activists with scattergun priorities whose tactics are at times badly thought out. The group is then torn apart by an overzealous, self-appointed “leader” and political differences.

By the summer of 2016, the film ends at a widely reported protest at Heathrow airport. This coordinated day of action saw roads shut down in Birmingham,Nottingham andHeathrow. The date – 5 August – was chosen to coincide with the fifth anniversary of the fatal shooting of Mark Duggan by police. At the London demonstration, some of the former Black Revs members do appear to be organising under the “umbrella movement” of Black Lives Matter UK. However, the spokesperson for BLM UK tells me that some members were previously a part of London Black Revolutionaries, all the members of BLM UK are of African and/or Caribbean descent.

At the end of Generation Revolution Joshua Virasami, who is one of the public-facing BLM UK activists, tells the camera that organising under the Black Lives Matter UK banner has come with increased risk: “It’s been arrest after arrest. Police intimidation. Knocks on your door in the morning. Harassing your parents. Threatening your parents. Threatening group members. Heavy state surveillance.”

In 2016, tabloid papers ran a series of stories that aimed to discredit members of BLM UK, with large photographs of those involved. Later, in June 2020, the Daily Mail and The Telegraph both ran stories with photos of Joshua. The BLM UK spokesperson said this is the reason why some members won’t reveal their identities.

“For many years, BLM UK has been open, holding public meetings that anyone can come to. Doing press, doing interviews with people. This has led to attacks from the far right and the press. Journalists outside people’s homes. People’s family members being harassed by the tabloids,” they tell me. “Understandably, people are worried about their families safety as well as their own.” BLM UK say they have temporarily closed membership and plan to reopen in due course.

This follows a tradition of Black activist groups being tracked and monitored by the state. The existence of a Black Power Desk, a special branch of counterintelligence that sought to discredit the leadership of the growing British Black power movement from 1967, was revealed in 2010 by Freedom of Information requests.

Prioritising the safety of members is understandable, but it still raises questions of how transparency and accountability can co-exist with anonymity.

A million-pound fundraiser

From 2016 until June 2020, BLM UK state they had so little money they had no need for a bank account. They say the group had only run one fundraiser before this, as a coalition of campaign groups to raise money for the bereaved families of Black people who had died in police custody and the solidarity demonstrations they ran. It raised £8000, the majority going directly to families.

“We had no website. No money to run workshops at colleges and schools. Nothing for our legal observing [trained volunteers that support activists at protests],” the spokesperson tells me. The fundraiser opened on 2 June and has raised over a million. “We could never have envisaged such a huge donation. We were thrilled, excited but it’s also a huge responsibility as well. Because we’ve never had funding before we weren’t set up as an official organisation. We had no bank account. We had no board of directors, no trustees.”

While a number of grassroots groups organising under the BLM umbrella have raised money to support their work, such as the youth-led All Black Lives UK, BRISBLM (Bristol) and Tribe Named Athari (formerly LDN BLM), the size of BLM UK’s funds has led to questions online over how the money will be spent. After three public-facing members tweeted that they were leaving the group due to “political differences”, with a note that the money raised needed to be “distributed directly to Black* [*of African and Caribbean descent] communities”, rumours also circulated that the money would not necessarily be earmarked for Black-led organisations.

The BLM UK spokesperson emphasised that the money has not left GoFundMe as the group is in the process of setting up as a formal organisation. A spokesperson for GoFundMe confirmed that until BLM UK has a legal structure in place, no money will be deposited.

“We could never have envisaged such a huge donation. We were thrilled, excited but it’s also a huge responsibility”

“We’ve been able to hire a lawyer who is setting up the bureaucratic structure we need so we can set up a bank account and receive the funds. We’re going to be registered as a community benefit society. This is an organisation that works to benefit a specific section of society (in our case Black people),” the spokesperson tells me. “This means we can do political work, like criticise politicians, which a lot of charities are unable to do. But this will provide the legal structure, accountability and transparency that other organisations such as charities have.”

BLM UK say they will continue to show solidarity with multi-ethnic organisations that do work they believe to be important, such as Sisters Uncut, by platforming fundraisers and direct actions. These organisations will not be able to apply for funding from them. Only Black-led organisations will be able to apply to do so. This includes Black-led organisations that have a remit outside of the black community – for example a Black-led organisation that organises against deportations. BLM UK will have a board of trustees that are publicly named and accountable.

But accountability extends beyond funding and its distribution. It also includes being responsive to the Black community when concerns are raised by members that face marginalisation across identities.

Antisemitism accusations

In response to the Israeli government’s plan to annex parts of the West Bank in June, the UKBLM Twitter account said: “As Israel moves forward with the annexation of the West Bank, and mainstream British politics is gagged of the right to critique Zionism, and Israel’s settler colonial pursuits, we loudly and clearly stand beside our Palestinian comrades. FREE PALESTINE.”

According to almost 50 UN experts, this annexation would have contravened international law and calls for sanctions grew internationally. However, the wording of the tweet faced widespread criticism.

“The language used in the tweet had antisemitic undertones, sparking an age-old trope that plays into conspiracy theories that Jewish people control governments, the media and other institutions of ‘power’, In this case, ‘gagging,’” says Lara, a Black Jewish woman who writes about her experiences. “Some would argue that Israel and Jewish people are not the same; the issue here is the undertone that leads others to connect Israel to Jews and to the message.”

“The language used in the tweet had antisemitic undertones, sparking an age-old trope that plays into conspiracy theories”

When she tweeted that there were ways of expressing solidarity with Palestinian people and not falling into antisemitic tropes, she received online abuse from trolls. Two other Black Jewish women also received abuse. Lara felt BLM UK’s show of solidarity was muted. “There was no acknowledgement about what led to the abuse, i.e. speaking out about their tweet,” she says. “An explicit tweet condemning the abuse and an expression of solidarity towards Black Jewish women that also condemned attempts to marginalise our voices would have sufficed.”

She has offered to have a private discussion with BLM UK, including via her open DMs, but has yet to hear a response.

The BLM UK spokesperson says they weren’t personally aware that she had reached out to the group but that BLM UK has been speaking with Jewish groups since the tweet.

“First and foremost – BLM stands against all forms of racism including antisemitism. As soon as people identified the fact that they found the language problematic in the tweets, we worked quickly and carefully to clarify our points,” they tell me. “We’ve been learning from our Jewish comrades opposing both the Israeli state’s violence and antisemitism so we can stand in solidarity with them and the Palestinian people.”

The clarification thread outlines the political thinking behind the tweet but does not comment on the language used.

BLM UK says on its GoFundMe page that it is committed to lifting up the experiences of all Black lives who are marginalised. Lara feels there is more work to be done by BLM UK and the wider Black community to be in solidarity with Black Jews. “Black Jews exist as do Black Muslims. Loving Black people means loving the diversity of who we are. For Black British Jews, antisemitism affects us as Jews and anti-blackness affects us as Black people,” she says. “The first step is to acknowledge that Black British Jews exist and have done so for many years in the lands we came from.”

Fighting for Black liberation by centring the lives of the marginalised will need to include Black Jewish voices too. But what does Black liberation look like to BLM UK and other BLM groups? And how do they plan to get there?

Black liberation in Britain

With a number of autonomous groups organising in the name of Black lives, it can be difficult to keep up. The theory of social movement ecology sees this as the strength. A network of groups working independently towards shared goals increases the probability of success. Each approach plays a role within the “ecosystem”. They are separate entities that work together.

Tyrek Morris, co-founder of the youth-led All Black Lives UK says this is key to how BLM groups work. “There’s a few of us that work together because ultimately we’re all fighting for the same thing, which is Black liberation. How we do that is all different. But actually, we’re all one.”

The protests that initially sprung up across England were organised by youth-led groups like All Black Lives UK, who planned the famous protest that ended with the statue of 17th-century slave trader Edward Colston plunging into Bristol Harbour. Other BLM organisations, including BLM UK and Tribe Named Athari gave them legal support and provided media training and safety tips for young activists. As the wave of protests brought more media requests in on its crest, their spokespeople took on some of the interviews.

Although protests will continue, BLM groups are looking at their long-term goals. All Black Lives UK have coalesced around five demands for the government: end racial discrimination in criminal justice, reform the education system, end racial health disparities, implement the recommendations from race reviews and stand in solidarity with the Black community in the US. “As we progress we’ll push for more things,” Tyrek tells me.

BLM UK’s longer-term political vision and demands include increasing community safety and harm reduction, empowering young people, community-led mental health support, women’s services, youth services and education for young people, as well as investment in housing and employment. They see “eroding the power of the police and prison system” as key to achieving this, but done in tandem with preventative measures like investing in youth centres, domestic violence services, social housing and mental health services. This is what they mean by “defunding the police”.

To make change of this scale requires a social movement. “We’re thinking about how to build sustainable links with new BLM organisations that have sprung up across the country as well as other Black and anti-racist organisations,” the BLM spokesperson says.

BLM UK has an unenviable task ahead. Immense public scrutiny and the threat of violence. The pressure of a transformative number of donations and the responsibility for delivering on the promise that’s implicit in their name: Black liberation. The joy of a social movement is that they are not alone in their battle. We can all play a role in the fight for Black lives; for liberation and for justice. To win, we must organise together, get things wrong, get things right, hold one another accountable but in good faith, be willing to listen and grow. If we don’t, we will fail. Time will tell which path we take.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?