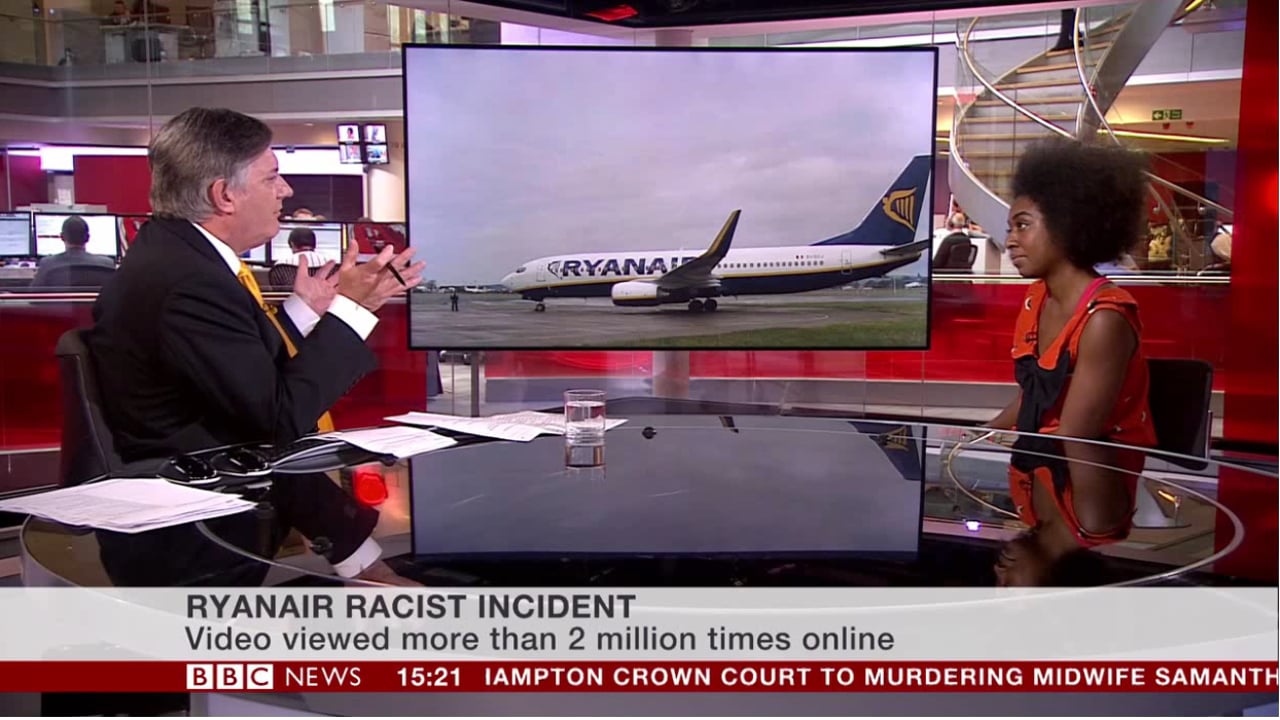

Still via BBC News/YouTube

I am one of a number of women of colour who are regularly called up by broadcast outlets to offer our opinions, upset or outrage in under five minutes. When these requests started out, it felt exciting to be asked, and like a real opportunity to shape public conversations particularly surrounding race. It’s a privilege to have a platform and to be able to speak on issues I care about.

But, as time has passed, I don’t think I’m the only one who’s feeling tired. Every couple of weeks, a clip goes viral from Victoria Derbyshire, Jeremy Vine or Sky that sparks discussion about the fairness of the format. The latest has been Extinction Rebellion co-leader Skeena Rathor being berated by Piers Morgan on Good Morning Britain in a blisteringly uncomfortable exchange that the programme decided it would be appropriate to make a meme out of.

Back in May this year, I watched author and Guardian columnist Afua Hirsch explain to a panel of white people why Danny Baker tweeting a picture comparing the royal baby to a chimpanzee was racist. Visibly distressed, Afua asserted: “I’m worried about the millions of black people who regularly live this kind of abuse, and then have to be in spaces where everybody denies that it’s a problem… I’m living it right now in this conversation.”

Not long after appearing on Sky, Afua tells me that “the cost outweighed the benefit” of her appearance on the show. “It’s not the first time but I felt that a line had been crossed and that it was beginning to be exploitative,” she says. “It was really a reminder that attempting to do racial justice work while being racially minoritised in a hostile space is traumatic. And I don’t want to send a message that it’s ok for us to be put in those situations.”

Although not necessarily our medium of choice, TV and radio debates are familiar territory for many writers and activists of colour. Most recently, the BBC has been a particular topic of scrutiny – where it seems the idea of “impartiality” is definitely a large part of the problem. The most common issue the women of colour I spoke to raised about broadcast appearances was that much of their emotional labour stemmed from treating certain subjects as being up for debate.

Jemima* a 23-year-old writer, says that the “two sides to every argument” approach can be reductive at best, and distressing at worst. “[BBC Asian Network] once had me on once to talk about abortion and contraceptives, but then brought out this very conservative Muslim family for ‘balance’, who literally basically called my life choices slaggy and haram on national radio.” In a statement to gal-dem, a spokesperson said that: “BBC Asian Network provides a platform for young people around the UK to have their say on the issues that matter to them. We invite a broad range of contributors to take part in our debates based on their knowledge and experience of the topic being discussed. All contributors are fully briefed beforehand and given the opportunity to discuss what they feel comfortable talking about on-air.”

“The BBC had me on to talk about abortion and brought out this very conservative Muslim family for ‘balance’, who basically called my life choices slaggy and haram on national radio”

BBC Asian Network contributor, Jemima*

Kim Mcintosh, a columnist at gal-dem, agrees that the experience often leaves her feeling entirely drained. “At its worst, they will ask you to debate your life with a clown for clicks and call it ‘a debate’. Then you have to go and have three wines to recover, whilst they cash in on your free labour… There is often a lot of men shouting. You feel mentally drained after it’s finished and then have to go back to your life or your trolls. And you probably did it for free.”

Rather than simply being emotionally laborious, author and activist Lola Olufemi says that the idea that you can be “impartial” or “balanced” about issues like racism, transphobia or misogyny is actively counterproductive to any systemic change. “An adversarial format for discussing structures of oppression will never work, the ‘two sides of the debate’ idea falls apart the second we are discussing real-world experience.”

“We can debate which colour is the best until the cows come home because colours are abstract. But issues of race, gender, class and other aspects of people’s humanity, are not.”

Oliver*, a producer at a BBC radio station who wants to remain anonymised, explains that without thorough discussion about nuance before the show, subjects can easily slip into looking like a polarised caricature of a given debate. This can result in us getting shouted down, whether it’s from other guests or presenters themselves. “Often, when a guest has a particularly strong opinion, the presenter feels like they have to play devil’s advocate with them, even if what they’re saying isn’t really up for reasonable discussion.”

After Naga Munchetty was ruled to have broken the BBC’s impartiality policy by discussing racism, I was woken up by a producer at the BBC and put on the spot and prompted to go live on air within three minutes. As Oliver points out, although these situations don’t happen all the time, “There is simply not enough thought going into the telling of so many stories… It’s ‘who can we get, are they going to say something controversial, or strong, or strident?’ If yes, great, book them.” Even if they have only just woken up.

Oliver tells me that the technical side of the process also exacerbates simplistic attitudes to complex discussions. “Guests are described in our system with a series of keywords that you can search, for example ‘race’, ‘racism’, ‘millennial’, ‘right-wing’ or ‘left-wing’ – that sort of thing. When it’s a case of using a broad keyword to search for a guest at really short notice, it just makes the whole process of booking guests, again, thoughtless and simplistic.” This means that, in theory, you can quickly ring up a “race” person to argue with a “right-wing” person and voila, you have yourself the formula for a debate.

“Guests are described in our system with a series of keywords that you can search, for example ‘race’, ‘racism’, ‘millennial’, ‘right-wing’ or ‘left-wing’”

BBC radio producer, Oliver*

When we consider this, serious questions arise about how effective such a format can be in shaping public opinion. Lola, who has appeared on The Jeremy Vine Show and Woman’s Hour, argues that there are serious limits to what a simplistic debate of around five minutes can achieve. “It shows is a wild underestimation of audience, demonstrating that 1) these programmes don’t care about the substance of the issues they discuss, and 2) the assumption that their audience won’t understand anything outside of a three-minute soundbite.”

She adds: “There’s no room for nuance or considered discussion in the mainstream pundit cycle, it’s about hitting certain points at certain moments without stuttering or skipping a beat.”

Kim thinks the main problem is less the format, and more the type of debate and the terms they are built on. “The way these shows are structured – controversy, clicks, shares, trolling – require a lack of nuance that opens you up to misinterpretation and online abuse. No thanks.”

“Only bringing us on to talk about golliwogs and ‘culture wars’ reinforces the idea that racism is trivial rather than grossly affecting life chances in this country. I’m sick of it. Ask me about inequality or discrimination.”

Specifically with regards to discussions on race, Oliver tells me that from the production side of things, there’s often a lack of consideration put to how a story is framed and approached on the air. “I don’t know if this is because editors don’t care, or simply don’t understand the nuances of the story well enough. Once I remember just being told: ‘we need someone black’.”

Many contributors don’t know that you can request money for TV and radio appearances, because producers usually do not mention fees at any point in the process. “I have gone all the way to Manchester for BBC Breakfast, been cancelled the morning of, and not offered a fee. I didn’t even know people could ask for fees,” Kim says. When contributors do request them, fees for appearances are usually between around £20-£50 – this rate is arguably high for 10-15 minutes of a contributor’s time. But it’s also worth considering the emotional and energetic cost of being broadcast live across the country as you debate something as sensitive as racism and doesn’t always encompass the time spent travelling to and from studios. The National Union of Journalists suggests that “expert guests” – which is exactly what PoC speaking on racism are – should be negotiating for more.

Afua isn’t so sure that producers are intentionally exploiting guests. “These debates are set up by often well-meaning white people who have no personal understanding of what they are asking of us. There is no literacy around whiteness or the emotional violence of dehumanising people already in a minority by denying their experience.”

She adds: “While producers need to be becoming more sensitive to this, the opposite is happening. The commercial pressures of broadcasting mean there is a temptation to deliberately engineer these scenarios as clickbait.”

My main gripes with producers last week surrounded the way I was treated in the pre-interview process – being woken up at 7am and then pushed to go on the air when I wasn’t prepared. To me, it feels like it fits into the broader climate Afua and Jemima discuss – where women of colour are just mouthpieces in a for-and-against game of ping pong, without much thought to our emotional wellbeing.

Oliver tells me the fast-paced nature of shows, and booking guests at extremely short notice, is a real problem. “This happens far too often, is actually very rude in my opinion and inherently means that the journalism is sloppy and simplistic.”

He also says that last-minute editorial decisions often create situations where “the guest and presenter are unprepared, and [so] the guest feels like they are ambushed by a question they don’t have an answer for, or are pushed into being more strident than they would otherwise be.”

“I have gone all the way to Manchester for BBC Breakfast, been cancelled the morning of, and not offered a fee. I didn’t even know people could ask for fees”

Kim Mcintosh, gal-dem columnist

What this leaves me wondering, while my phone blows up with calls from “No Caller ID” (a giveaway that the BBC is on the other end of the phone), is if it’s worth engaging in these debates at all. Are there any positives to this type of discussion? And if so, how do we weigh up whether it’s worth it or not? Most people I spoke to came to slightly different conclusions.

While Jemima told me she won’t do them anymore, Kim says that under some circumstances, there are huge benefits to making these appearances –for example if you’re working on a campaign. “For campaigners, access to mainstream platforms can help bring your message to new audiences. When it’s good, you can change government policy with a powerful message, and sometimes people reach out to let you know how it made them think or feel.”

For Afua, it’s about taking a number of personal and political factors into consideration. “My general view is that these conversations are happening, we all see them, and that it’s important for our voices and perspectives to be represented. I think you have to have some level of belief that the benefit of being part of the debate outweighs the cost of potentially legitimising a conversation that relies disproportionately on our emotional labour as people of colour.”

She says that despite this, it’s still important to be selective. “I’m constantly weighing this all up, and I know that the minute I feel that the cost is too high, or the benefit for us as a community too low, I know I’m not doing it.”

As Kim points out, on-air discussions and debates aren’t always fraught, exploitative and cyclical – and there is still hope to improve the way the industry operates as a whole. But she thinks that calling people five times in a row in the early hours of the morning, and general unpaid labour, needs to stop. “Why would I go on BBC if I can write an article and actually get paid to comment instead?”

Lola thinks that for these conversations to become productive, broadcasters would have to hold far more faith in their audiences than they currently do. “If you look at shifts in public understanding about the most complex issues, there’s more than enough evidence that people can handle complicated, specialised, radical knowledge. But that threatens the power of the cultural gatekeepers who create and run these shows.”

Jemima is highly sceptical of the idea of changing mainstream broadcasters from within – particularly the BBC. “There’s so much stuff that runs deep – it’s an institutional sickness – and I really would advise PoC to not allow themselves to be chewed up inside of it. This is an institution that is racist from the ground up, and we shouldn’t trust it with our stories, experiences and conversations.”

Afua, however, believes that you can do both at the same time. She says: “I have to know I’m part of the solution working towards us running our own platforms and spaces where we can curate the conversation. That’s a long term project I believe in, and if I can strategically use these appearances to get there, then that’s motivating.”

“We need to keep supporting and controlling our own means of production. If we didn’t have to waste so much energy on what should be so basic, imagine what we could create?”

gal-dem has reached out to the BBC for further comment and will update this article with their responses