Now that Danny Baker’s been fired by the BBC, a brief history of ‘monkey racism’

Micha Frazer-Carroll

09 May 2019

Image via Twitter

If you have a Twitter account, phone or internet connection, you’ll know by now that Danny Baker said something very racist. Yesterday evening, a racist image cursed our feeds – Danny tweeted out a black and white picture of a small chimpanzee dressed up in a suit, sandwiched between two “parents”, with the caption “Royal baby leaves hospital”.

Of course, it would take a “joke” directed towards a member of the royal family to cause the BBC to so swiftly extend their HR arm but while Danny has defended himself (poorly and angrily), it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to see why the joke was racist. But grotesque comparisons between black people and monkeys, chimpanzees and other apes have a history that is centuries old, with a worrying number of examples making headlines in the past year.

As there are many, many other examples of how this comparison persists to present day, it’s safe to say that this form of racism is still alive and well. While Danny Baker insists that his tweet was misinterpreted, and not racist – we’re not convinced. After a brief look at the history of “monkey” racism, we can confirm that we’ve seen this all before.

Medieval myth

The myth of the “simian”, a devilish, black, ape-like creature, dates back to the Middle Ages. Christian discourse saw simians as representatives of lustful and sinful behaviour.

This comparison became racial in the 17th century, as French philosopher Jean Bodin wrote of Africa as “a hotbed of monsters, arising from the sexual union of humans and animals” – i.e. insinuating that Africa was an evil and treacherous place inhabited by human-animal hybrids.

This idea of “simianisation” persisted, and both explicitly and subtly made its way into disciplines spanning anthropology to biology to medicine.

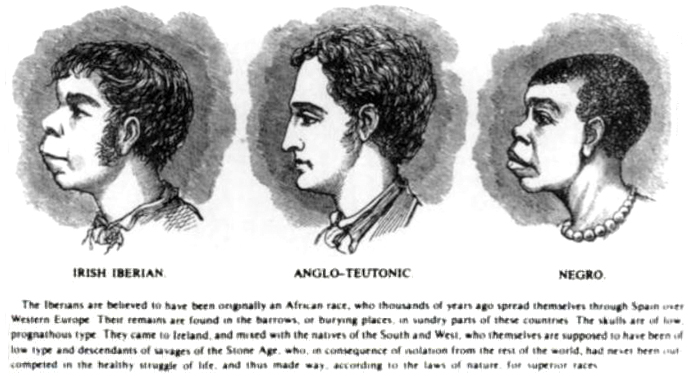

Eugenics

The enlightenment period saw the dawn of eugenics and scientific racism – which looked to make conclusions about different races’ behaviours from their genetics and physical characteristics. During this period, between the mid-1600s and early 1800s, Western scientists were obsessed with ranking and hierarchy between different ethnic groups, and commonly made comparisons between perceived similarity in physical characteristics between humans and non-human primates.

18th century French naturalist and zoologist Georges Cuvier was particularly into deciding which groups’ skulls were seen as “beautiful” and “ugly”, and wrote of black people:

“The Negro race… is marked by black complexion, crisped or woolly hair, compressed cranium and a flat nose. The projection of the lower parts of the face, and the thick lips, evidently approximate it to the monkey tribe: the hordes of which it consists have always remained in the most complete state of barbarism”.

Meanwhile 19th century Darwinist Ernst Haeckel wrote that “Negroes” have stronger and more freely movable toes than any other race, and thus are more closely related to non-human primates. His racist comparison positioned Negroes as “four-handed apes”. This way of thinking was crucial to eugenicists and colonisers – and served to equate blackness with being animal and “uncivilised”.

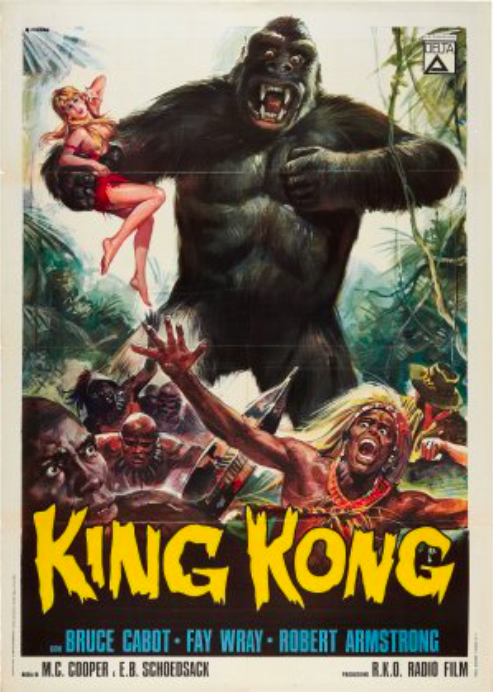

20th century cinema

The release of King Kong, seen as a historic landmark for some, served as a racially dangerous moment for others. The production and release of the film coincided with the 1931 false conviction of Scottsboro Boys, a group of nine black teenagers accused of having raped two white women. Coverage of the trial and of the film ran alongside each other, and metaphorically, also sometimes overlapped – with a 1935 picture story depicting one of the boys as a monstrous ape-like figure, baring its teeth and dragging a white woman away.

The messaging of the film is similarly shrouded in race politics. The first King Kong is set on the fictional, African-coded Skull Island, and follows the story of an ape who is captured, chained, brought to America, captures a helpless white woman, and destroys the city. You can take from that what you will, but many critics and scholars have pointed out that these mirrored the racial tensions of the time.

The Windrush generation

When the Windrush generation of Caribbeans came over to the UK between 1948 and 1970, monkey noises and comparisons were common forms of abuse. “I was called black monkey, asked if I came on the banana boat, and told go back home,” Windrush migrant David Jameson told the Guardian of his time as a child in the UK.

In Winsome Pinnock’s play Taking Leave, which was performed at the Bush Theatre last year, this form of interaction was dramatised, where one character is told “show us yer tail, yer black monkey”.

In modern politics

In November 2016, West Virginia county worker Pamela Ramsey was sacked from her position for a Facebook post that compared then-First Lady Michelle Obama to an “ape in heels”. Clay County Mayor Beverly Whaling commented under the post: “Just made my day Pam.”

In fashion

H&M came under fire in January 2018 for choosing a black boy to model a hoodie that read “coolest monkey in the jungle”. Even if this one was an oversight – many tweeters rightly pointed out the age-old comparison.

In December last year, Prada recalled a $550 monkey figure that also looked a lot like a minstrel-style golliwog, after being called out for racism and a presumable lack of black people on its staff.

In sport

Monkey noises and gestures directed towards black sportspeople are common, both in the UK, mainland Europe and the US. Although FIFA’s anti-racism taskforce disbanded in September 2016, stating it had “completely fulfilled its temporary mission”, Raheem Sterling was on the receiving end of monkey chants when playing against Montenegro earlier this year. The likening of black players to monkeys doesn’t end there – a banana was thrown at Mario Balotelli by Croatian fans at Euro 2012.

This week, the BBC also reported that the issue is prominent in kids and teenagers’ football, with under-14s being said to regularly leave the pitch in tears in response to monkey chants.

“Monkey racism” is embedded in the collective memory – and it shouldn’t be forgotten. For anyone who’s unsure about the seriousness of comparisons between black people and apes, it’s important to remember that “jokes” like this carry historical significance and serious implications.