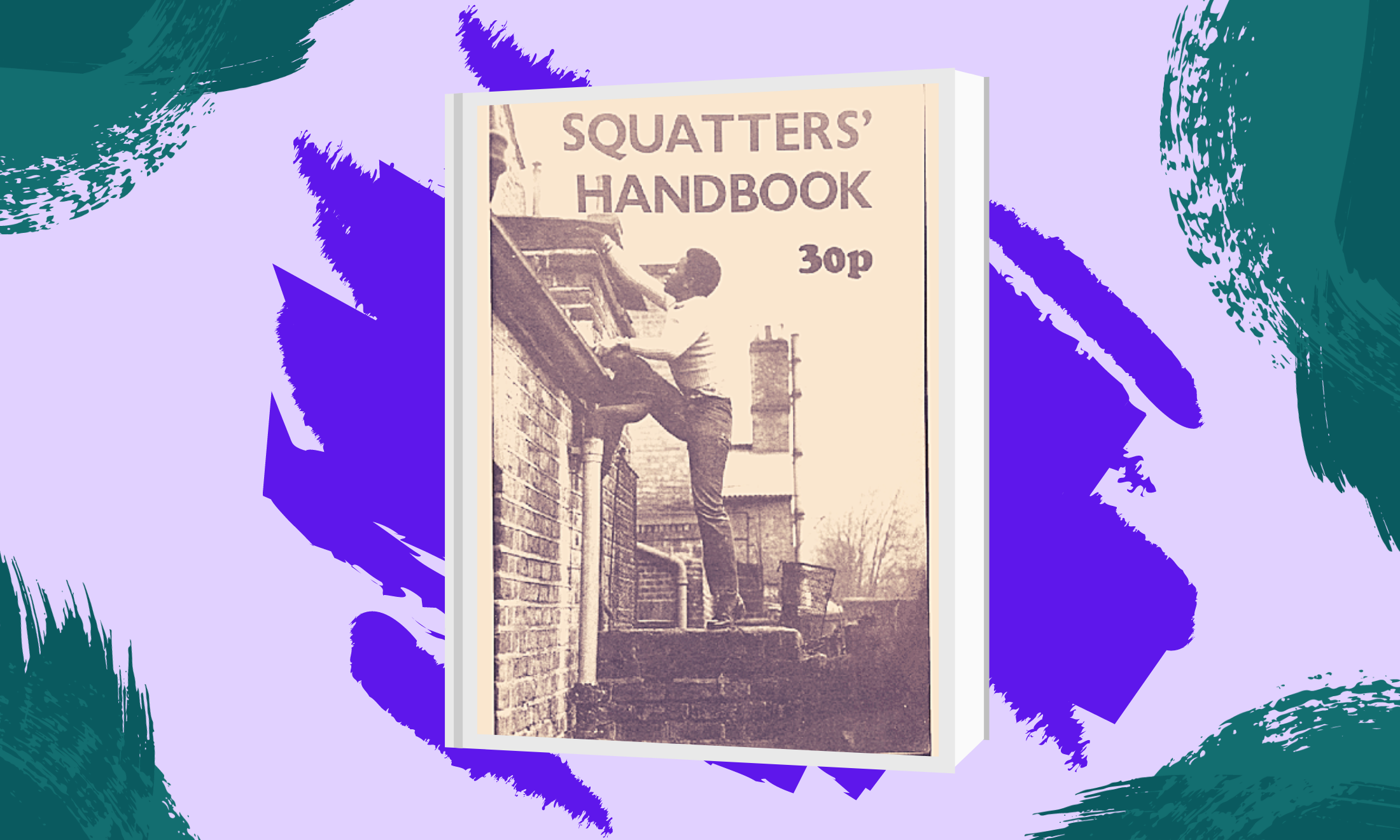

Advisory Service for Squatters/Lambeth Archives

Our house: why protecting the right to squat is a defence of radical Black history

As a new bill seeks to crackdown further on squats, one writer explores the radical Black history built around the squatting movement.

Lisa Insansa

12 Apr 2021

Squatting has been a means to live, resist and organise for generations. The unused buildings that spill over a city’s landscape and latent land that grounds our surroundings become used and repurposed by homeless people, activists and those seeking – or who are forced – into an alternative lifestyle. Squatting has also played a key part in radical Black British history, a history that is continually under threat. The recent proposed Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts bill (PCSC) only furthers this threat, dragging the squatting movement and Black radical history in the maelstrom of authoritarian state violence.

Over the years, squatters’ rights have been slowly eroded as successive governments have allied with property developers and private landlords. For a long time, it was legal to squat (the act of occupying an empty building or piece of land) a residential building. However, in 2012, a change in legislation criminalised this type of squatting and made it only possible to occupy commercial properties. Today, if the new PCSC bill gets passed, it would become a criminal offence to trespass on private property (currently it’s a civil matter) where a vehicle is present, directly affecting GRT communities who could instantly lose their way of life, as well as squats that rely on vehicles, and ultimately providing a stepping stone to the eradication of squatting altogether. This is a worrying reality for those who have nowhere else to go and for those who use squats as a political tool.

While the squatting community can often appear as just another white-dominated space, it is important to recognise the legacy of Black squatters and how they weaved their cultures and strategies of resistance into the movement. After the Empire Windrush docked on British shores in 1948, helping to kick off a wave of Caribbean migration, thousands of Black people moved into cities that had been chewed up by six years of war. This flow of migrants found themselves locked into a crisis where the supply of decent and affordable housing was diminished, and the roots of institutional racism were firmly planted.

“It is important to recognise the legacy of Black squatters and how they weaved their cultures and strategies of resistance into the movement”

By the 1970s, the Black Caribbean community were tired of waiting at the end of council housing lists and being squeezed into one-room accommodation. Squatting became a necessity for some, as well as a political action against housing discrimination, meagre dwellings, gentrification and the ubiquitous racism of the state. A 1974 essay from Race Today on the topic of squatting explained that initially there were few Black people in the squatting movement of the late 1960s, due to a “cautious approach” bred as a result of being a minority immigrant population. However, as Black radical movements took root in Britain, the causes became intertwined and through the 1970s and 1980s, squatting – reclaiming and repurposing buildings – became a vital part of radical Black organising, especially in London.

Brixton in particular was the hub of political squats, not just for the Black radical tradition, but for white anarchist movements, LGBTQI+ communities and those who were rebelling against the authoritarian state. For example, the legendary 121 Railton Road squat in Brixton, which was opened in 1973 by Black British Panther and key Black squatters’ rights activist Olive Morris and her friend Liz Obi, ended up being re-squatted by these different movements until the end of the century.

While Black and white squatters would live on the same street and share information amongst each other, the experience of the two groups were not the same: “That the young blacks have been informed by the white squatting movement is true, but their squatting activities are qualitatively different from it,” continued the 1974 Race Today feature.

“The black squatting movement in Brixton has broken new ground. It is local council policy that the single person does not qualify for public housing and therefore the black youth seemed destined for a life of homelessness or hostel existence […] They will not tolerate the one-roomed existence offered them nor continue to sleep rough and be objects of liberal pity.”

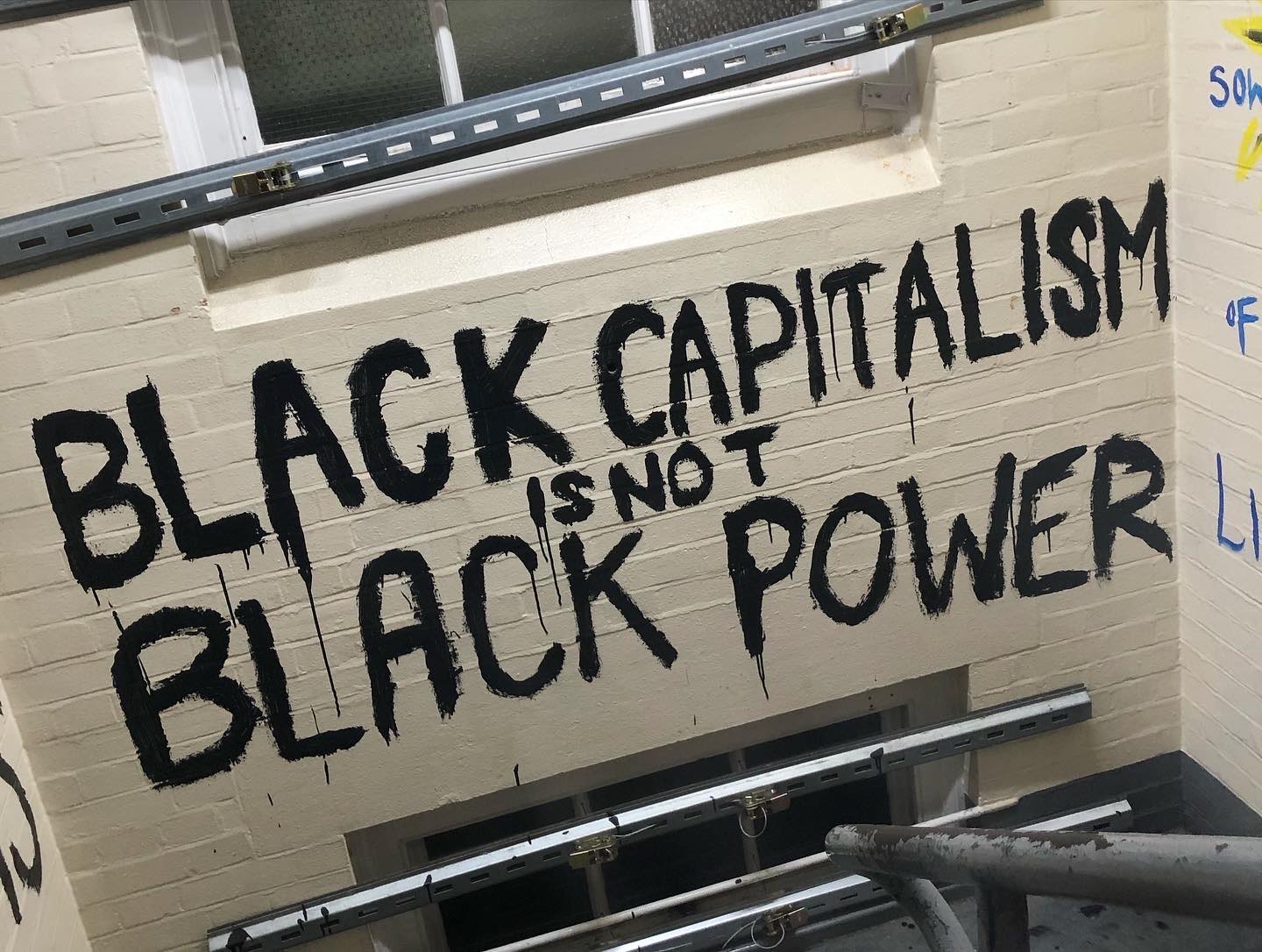

Through the squatting scene, Black Caribbean communities were able to set up radical bookshops, reggae and blues clubs – or shebeens – social centres and meeting spaces for activists. Groups such as the British Black Panthers and Brixton Black Women’s Group resisted the thieving nature of landlords and the grasping hand of the state by occupying these buildings and centring them in the community. This history is especially profound considering that London’s most “attractive” buildings were paid for with money drenched in the blood of enslaved and colonised Black people; in this way, their squatting can be viewed as reparatory justice.

“Through the squatting scene, Black Caribbean communities were able to set up radical bookshops, shebeens, social centres and meeting spaces for activists”

Squatting also opened and continues to open doors that would have otherwise put pressure on movements: having a rent-free physical space to live and organise means that the weight of working a full-time job is lifted, freeing up time, money and energy to put into activism and bringing the community together. On top of this, the act of living in a communal setting can provide ground for the constant exchange of ideas, skills, trust and understanding between people in the movement, as well as breathing an air of autonomy and freedom necessary for revolutionary struggle. It should not be a privilege to be able to do these things, but a human right. In the free society to come, a society without money and property ownership, we will essentially all be ‘squatters’. Residing and interacting with the land on our own terms will afford us the time and energy to connect to those around us without the normalisation of exploitation that gives rise to white supremacy, patriarchy, ableism and queerphobia.

Today, the memory of Black squatters has been wiped from much of our consciousnesses. Certain Black squats met a tragic fate through arson attacks, police raids and evictions, amped up by the 1981 Brixton riots which increased policing and targeting of Black movements and Black culture. The general squatting movement also suffered massively from Thatcherite policies like “right-to-buy” – a scheme that reduced social housing values in order to encourage tenants to purchase their rented dwellings. This liberal policy drew a sharp line between respectable and illegitimate ways of living, economic productivity and laziness, citizens and outlaws, subsequently condemning squatters to the realm of parasites.

More stringent measures in place to clamp down on squatting and an expanse of neoliberal ideologies has pushed oppressive hands into peak capitalist initiatives such as property guardianship. This is where property owners rent out rundown buildings – or would-be-squats – at the almost usual market price of ordinary rented accommodation. This not only short-changes the people who have no option but to rent such dire accommodation but acts to rid squatters of their homes and spaces while commodifying the tenets of squatting itself.

Despite this, squatters still fight for their right to occupy buildings. The recent occupation of a disused police station in Clapham Common, 200m from where Sarah Everard disappeared and in reaction to the insidious PCSC Bill, highlights the political power of squatting. This occupation saw a coalition of squatters, feminists, anti-fascists and Black liberation groups enter the building, which spread anxiety through the establishment and resulted in a brutal eviction, where bailiffs violently attempted to take protesters off the roof of the building and off a crane. One instance saw a young Black woman who was defending the building being dropped down a roof hatch in aggravated intent; other occupants were detained in handcuffs and faced injuries.

“This occupation saw a coalition of squatters, feminists, anti-fascists and Black liberation groups enter the building, which spread anxiety through the establishment and resulted in a brutal eviction”

We can also see the continuation of the Black radical squat legacy through groups such as House of Shango in Brixton, which operates as a home for Black activists and community action, providing free food, clothes, herbal medicine and political information . This act of resistance comes in the wake of closing youth centres and social spaces which have uprooted diaspora culture and communities.

If we let squatting die at the hands of authoritarian state power, we will lose a base for positive change. Britain currently has more than 600,000 empty buildings that will continue to rot in front of the eyes of those with nowhere else to go.

Squatters live amongst the discarded, in the rubble of a state that turns its back on the undesirable. A state that paints over the engravings of our culture on those so-called decrepit walls, and swallows whole the spirit of community in favour of a loveless enterprise.

In the famous words of Olive Morris: “I won’t come down until you let us have the building” and the people will not tire until they have their freedom.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?