Illustration by Nicole Chui

Inside Leicester’s ‘servant’ factories underpaying workers in the pandemic

Boohoo and other e-commerce sites have made a lot of money this year, but at whose expense?

Amber Sunner

21 Oct 2020

The narrow, dark car park which led to the fast fashion factory was full. South Asian folk music could be heard faintly through the factory windows. Despite the localised lockdown in my hometown of Leicester and the fact that the factory hit national headlines in July for its less than minimum wage pay, there was certainly life inside the red brick building.

The atmosphere in the reception of the factory I visited during the city’s second localised lockdown was gloomy. The walls were crumbling and little light streamed in from the flimsy entrance doors. I visited at 4pm but workers were still coming in and out speaking Hindi and Punjabi. As I speak the latter, I approached one asking politely whether this was the factory that allegedly supplied clothing for glamorous fast fashion brands like Boohoo and Nasty Gal. Locals had already pointed to the location as being the factory that made the news.

Inside the UK’s factories, as the pandemic rages, conditions worsen. This month, the Guardian reported that since July UK garment workers have been so systematically underpaid that they’ve been “robbed” of £27million. The combination of already-existing economic hardship and a pandemic that has a harsher medical and financial impact on minority ethnic households makes these unchecked factories an exploitative danger.

Over the last year, the city has come under growing scrutiny as HMRC found it had more cases of underpayment than most other cities in the UK. A report compiled by campaign group Labour Behind The Label found that Leicester’s already illegal working conditions became even more unlawful when the pandemic struck. Specifically, they found “that conditions in Leicester’s factories are putting workers at risk of Covid-19 infections and fatalities”. Boohoo operations account for almost 75-80% of production in Leicester.

The factories in Leicester producing garments for fast-fashion brands play a large part in fuelling our insatiable appetite to buy more clothes than we need by producing absurdly cheap goods. Business boomed for Boohoo over the nationwide lockdown where they recorded an increase in April sales when compared to last year. It is believed that their continued operations are linked to the second lockdown as cases shot up among factory workers.

Charlotte Robinson, 23, is a former worker for a Leicester factory. She designed clothes for the likes of Boohoo and Pretty Little Thing for a year. “At one point there was a fire in the night and the roof collapsed in but they were still told to carry on working,” she tells gal-dem. “Some of the girls looked [really young] and I rarely saw them have breaks.” She also reiterated the claims she made in an Instagram post in September where she revealed that there were rats “dead and alive” at work and that the “whole building had to share one toilet”.

It’s been a dehumanising summer for the diverse Midlands city. Leicester was the first place to experience a localised lockdown, which started on 29 June. With almost 40% of the population being Asian a lot of news stories were illustrated with pictures of Muslim women. Many felt this boosted the false idea that people of colour were to blame for the local spike. Information from the government was scarce. Local businesses were shut for flouting Leicester-specific guidelines despite the majority of the country being allowed to open. While the rest of the UK returned to normal, my city was gripped with fear.

In 2015, it was found that one in four Leicester residents live in areas of high deprivation. A high proportion of those who do live in these areas are said to work hand to mouth, meaning that when the pandemic struck they were forced to either go without money or risk their lives by continuing to work.

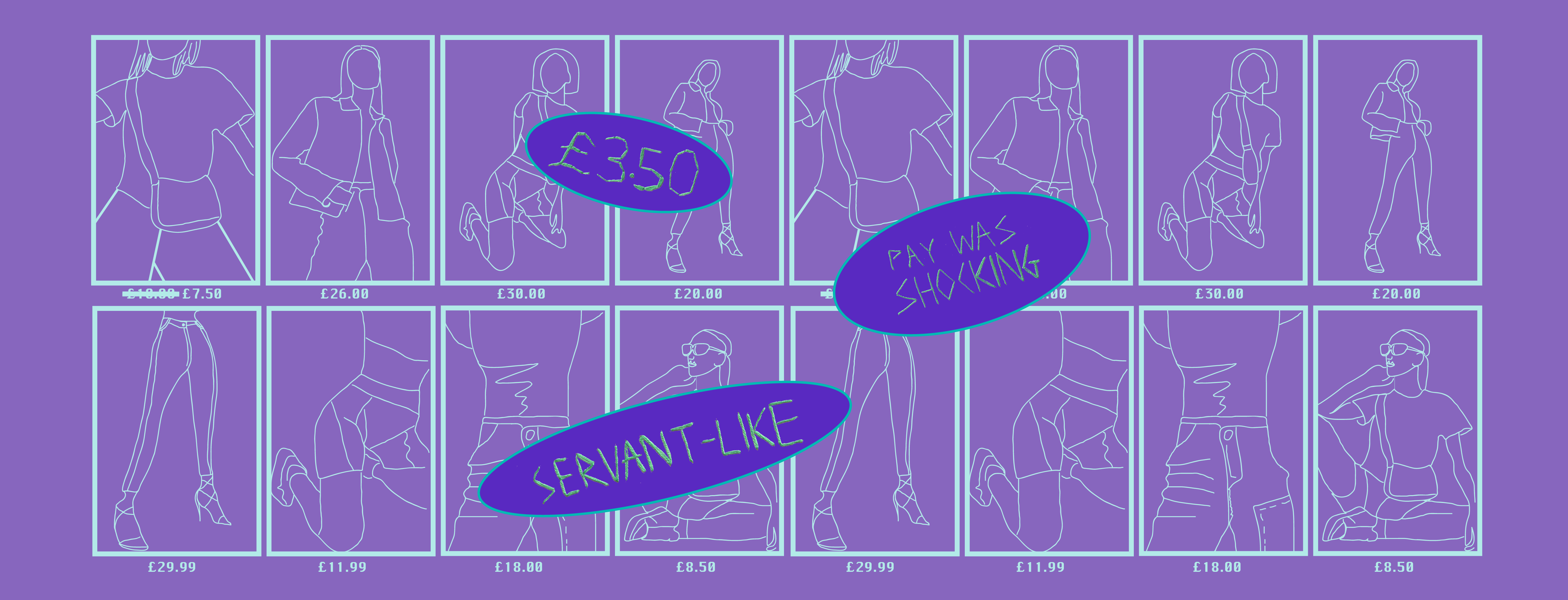

At the beginning of the pandemic, The Sunday Times’ Vidhathri Matetv released his findings from being undercover at a “sweatshop” in Leicester which supplies fast fashion brands like Boohoo and Nasty Gal. He reported that workers were being forced to do “back-breaking” work in “hot and cramped” conditions for £3.50 to £4 an hour without PPE. In contrast, Boohoo’s co-founder Mahmud Kamani became a billionaire in 2018. Umar Kamani, founder and CEO of fast fashion retailer PrettyLittleThing.com boasts his lavish lifestyle on Instagram. He posts photos of himself at Nobu in Malibu wearing a pair of £450 Gucci slippers, hanging out with P Diddy at the Grammys or posing at the wheel of a yacht on Italy’s Amalfi Coast.

“At one point there was a fire in the night and the roof collapsed in but they were still told to carry on working”

“Covid has had a really funny way of showing us all basically the worst of humanity andcertainly the worse when it comes to brands,” Orsola de Castro, co-founder and creative director of Fashion Revolution IV says over the phone. The organisation is a coalition of designers, academics, and producers in the industry who want to make a change. He believes the government is not listening despite mounting evidence that the UK has sweatshops that are “unregulated”. “Being in Leicester or being in Florence or Italy or the East end of London doesn’t guarantee that people are treated fairly and resources are used correctly.”

A worker recently told a Pukaar News reporter that there were no masks, social distancing or other measures to improve hygiene being implemented. He left his job because he felt unsafe in the work environment. When Leicester became the first city to have a second lockdown it was anecdotally linked to these factories. Speaking to Deputy Leicester City Mayor, Councillor Adam Clarke he’s not too sure you can confidently state cause and effect. “When the revelations came out it was the time when Leicester was going into local lockdown and the allegations linked Covid with exploitation in the textiles sector. I’m not saying that there wasn’t a link at all but it seems pretty clear that link was exaggerated,” he says,

Councillor Clarke wanted to make it clear that while a lot of this activity is happening in the city it “isn’t Leicester’s problem, it’s a problem of the textiles industry”. He adds that the problem lies in national legislation and regulation failing Leicester residents. “The city council don’t have any powers to enforce against tax evasion, health and safety issues or related issues in factories.”

While it is getting increasingly harder to find current staff who will go on record to shed light on the factory’s practices – for fear of retribution – there is a long history of similar operations in the city.

Jeeta Singh, 48, worked in a factory like the one I visited when he first moved to Leicester from India in the 90s. He says that the fact that the conditions haven’t changed was unsurprising to him. “You had no choice but to work in the uncomfortable and cramped conditions to make a living. I suspect the people working in the factories today face the same situation,” he says. The treatment was “servant-like” with bosses “talking down” to employees. “You were being watched all the time, constantly being told to work faster, and the pay was shocking,” he adds. Sometimes Jeeta was paid just £2.50 an hour.

Though Jeeta did have some positive moments in the factories he worked in, describing his colleagues as “family”, he talks about the situation today with great sadness, saying matter-of-factly, “Nothing will ever change, not in the near future at least”.

Jeeta’s English wasn’t good when he arrived in the UK and he only knew a few functional words, but he says that he never needed to talk English in the factory. This highlights the concentration of people of colour and immigrants making garments at that time. The Labour Behind The Label report found that this concentration hasn’t changed drastically either. It reported that “most garment workers are from minority ethnic groups”. Of these workers, almost 34% were born outside the UK from countries like India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh but Somalis and Eastern Europeans are also prevalent.

Amid this news, the Boohoo group only continues to grow and eat up other struggling high street brands. Boohoo Group revenues jumped 45% to £367.8m for the three months to 31 May, when compared with the same period last year. In June, having been relatively unscathed by the pandemic, it acquired Oasis and Warehouse in a £5.25million deal.

The behind the scenes of Boohoo is far less glamorous than the ads. Courtesy of Boohoo

All of this power and capital and yet it cannot seem to improve its supply chain. Gangmasters and Labour Abuse Authority was set up to help vulnerable and exploited workers in the UK across several industries. Its head of enforcement Ian Waterfield says they’ve been working with Leicester city council and Public Health England to safeguard workers. “No one should have to work in an unsafe environment, feel forced or coerced into doing so, nor have their labour exploited,” he adds. An independent review into Boohoo’s practice found that the company’s monitoring of its Leicester supply chain was “inadequate”. This was attributable to “weak corporate governance” which means the structures and rules currently allow poor conditions to slip through the net.

Boohoo responded to the independent review on 25th September 2020. They acknowledged that workers in their supply chain had “not been properly compensated for their work”. They made a commitment to Leicester’s garment industry workers which said they would: “Establish a Garment & Textiles Community Trust, governed by independent trustees, providing it with start-up funding and ongoing annual support.”

John Lyttle, Group CEO commented on the findings: “We recognise that Boohoo has been a major force in driving the textile industry in Leicester and today we want to reinforce our commitment to being a leader for positive change in the city, alongside workers, suppliers, local government, NGOs and the community at large.”

The company also announced that after allegations of modern slavery in their supply chains they are to set up their own “model garment factory” in Leicester. This model factory will ensure that workers are treated fairly and will employ 250 new staff. This is a step in the right direction from Boohoo, but the hope is that it sparks a wider change in all of Leicester’s unlawful factories.

My beautiful hometown is often depicted as a failed and unprosperous city. We have been victims of government neglect. The not-so-secret sweatshops have been known to Whitehall for years with no previous action. E-commerce behemoths swarm like vultures around this economically precarious Midlands community. As we ride this second wave, think not only of the essential workers forced to keep the country running but those working tirelessly to keep up with our insatiable appetite for Instagrammable looks.