Pretty Little Thing,

How the politics of representation mask fashion’s unethical underbelly

Seemingly diverse and inclusive branding is being used to divert our attention away from unethical and unsustainable business practices and shopping habits.

Hannah Uguru

07 Dec 2022

Self-indulgence in the form of consumerism defines the festive season. Accounting for around 2-3% of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP), the apparel and footwear industries are central to late capitalist values of flamboyant acquisition and display. However, the growing mood of eco-anxiety – underpinned by COP27’s focus on how exactly we’ll be financing global climate action – is changing the way we consume and engage with fashion.

Driven by increased consciousness around sustainability, e-thrifting has become the new normal among Gen Z and younger millennial shoppers, who are using reselling apps like Depop, Vinted and eBay. This year, fast fashion giants PrettyLittleThing (PLT) and Shein joined this recommerce marketplace by creating their own platforms: PLT Marketplace and Shein Exchange. By pushing themes of environmentalism and inclusivity, they’re tapping into enhanced priorities around ethical consumption and representation with what we wear. On the surface, these may seem like tangible actions towards better practices within a historically problematic industry. However, when placed against the backdrop of continued worker exploitation, corporate greenwashing and a culture of hyper-consumption, the limitations become clear.

The last three years have seen PLT widely condemned for their annual 99% off ‘Pink Friday’ sale, which sees hundreds of items sold for mere pennies during the last weekend of November. Days after the sale in 2021, they released an “inclusive” ‘them’ collection featuring non-binary and gender-fluid models to sell gender-expansive clothing. The timing made it feel like it wasn’t a genuine display of diversity and inclusion. More likely, it was an attempt to avoid addressing concerns over their continued use of sweatshop labour in the UK via predominantly migrant female workers. Moreover, the depths to which Shein is willing to stoop for quick profit – rebranding Muslim prayer mats as home decor and swastika necklaces as quirky jewellery while paying the workers who made them as little as 3p per item — undermine the company’s supposed desire to “build a future of fashion that is equitable for all”. Indeed, these modern companies are savvy at exploiting the political wants of the younger generation as a marketing tool, without making any material changes to their operations.

Racialised greenwashing

For Aja Barber, a writer, stylist and style consultant aiming to challenge the colonial, capitalist and patriarchal systems of power that shape our buying habits, this type of branding is something we should be wary of. “It’s almost like [fast fashion labels] are using this image of diversity like a bulletproof vest,” Barber says. For instance, a few months ago, PLT signed ex-Love Islander Indiyah Polack to be the first ever ambassador for their marketplace. With Polack, a young Black woman, as the initiative’s poster girl, consumers may be more likely to buy into their alleged goal of making fashion “more diverse, inclusive, and less wasteful”, and therefore engage with PLT’s new reselling app. Boohoo also appointed Kourtney Kardashian as their sustainability ambassador.

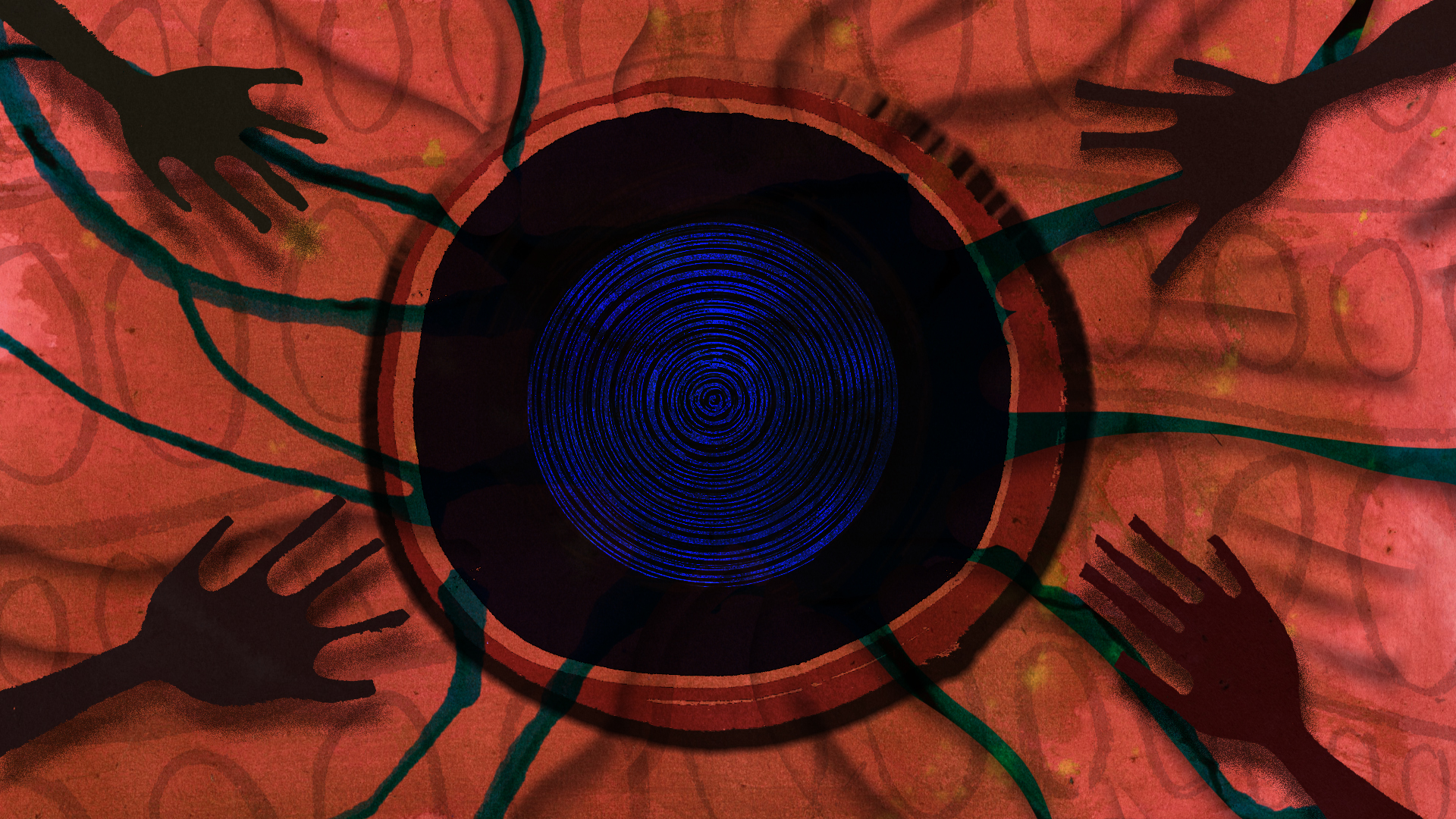

This diverts attention from the fact that fast fashion brands like Shein and PLT are known to introduce hundreds and even thousands of new apparel and footwear items weekly, contributing to the 400% rise in global consumption in the past 20 years. Many of these items are so cheaply priced that it can be more cost effective for the store to allow you to keep the item rather than process a return. This over-abundance of choice just compounds the perception of disposability (85% of textiles end up in landfills each year), in turn undermining the purported ‘slow fashion’ aim of these recommerce projects. For Barber then, BIPOC are the “shields” behind which brands hide their shady dealings.

This extends beyond influencer culture in the Global North and focuses on how garment workers are presented in the media. “If you go to a lot of brands, like corporate responsibility pages, particularly those that manufacture in the Global South, oftentimes you will be met with the picture of a smiling woman from India, Bangladesh, Indonesia, that sort of thing,” Barber says. “And it’s weird because they’re basically using a stock image photo of a woman in the Global South who may have been exploited by them to make you feel better because she’s smiling about their practices,” they continue. Approximately 80% of the world’s garment workers are women, predominantly from countries like India, China and Bangladesh, and just 2% of workers worldwide are said to earn a liveable wage – even when factoring in global variations on the cost of living.

Why is fast fashion so hard to quit?

Despite this apparent tokenism of historically marginalised people within the ultra-fast fashion world, its allure persists. Climate justice activist Mikaela Loach defines this phenomenon as “social licensing”, in which companies, institutions and systems can continue poor practices so long as they superficially present in the way consumers want them to. “As people and as a society, we give a lot of companies or institutions or systems a licence to exist by collectively agreeing whether they are ‘bad’, or they’re ‘good’, or they’re ‘okay’,” says Loach. “We don’t want diversity in who gets to be the oppressor. There can be powerful representation, of course, but I think sometimes that representation can cause more harm than good in the long term because it can allow companies to act with impunity.”

With this in mind, the logical conclusion would be to boycott, but this can be challenging for consumers – both practically and ideologically. More sustainable and ethically-sourced alternatives can be relatively inaccessible through cost and sizing options. In contrast, cheaper brands like ASOS, PLT and Shein offer extensive plus-size ranges that allow people with bigger bodies to engage in trends more freely, compared to standard UK size 6-16 ranges. In a world that sidelines larger bodies, especially larger women’s bodies, fast and ultra-fast fashion are often the most practical options.

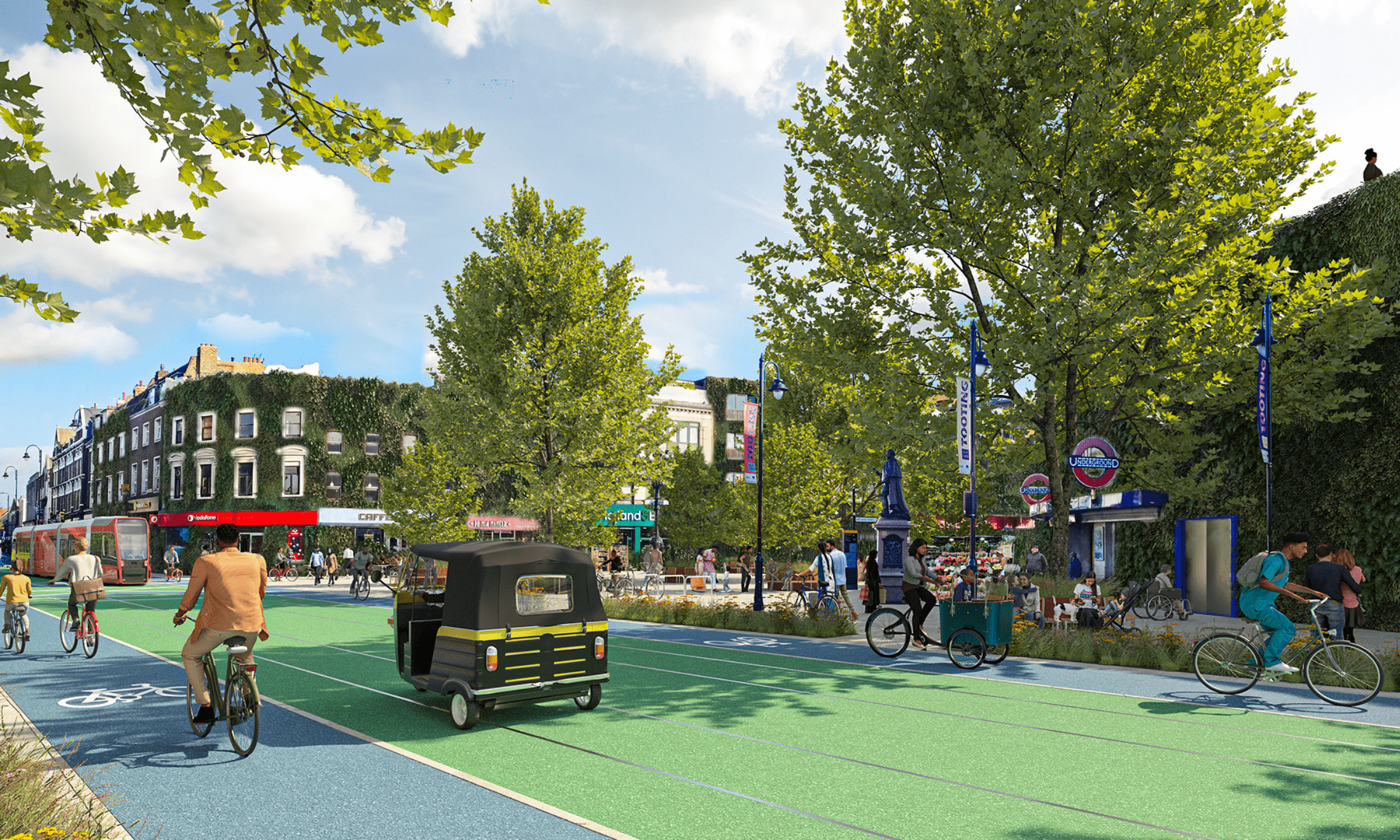

Fashioning a greener future

Buyers can feel like they’re caught between a rock and a hard place, but fortunately, there are independent brands that are doing the work to authentically marry inclusivity and sustainability. Angela Veljanoska is the co-founder and designer of sustainable womenswear label Monobrow and, as a business owner, understands the conflict of interest that many shoppers face. “We live in a throwaway culture where we’re exposed to cheap clothes that are convenient for people,” Veljanoska says, “so it’s hard for people to resist buying cheap goods – stuff that they can wear once – rather than spending a little bit more money knowing that the clothes are made ethically and sustainably.” With Monobrow items being made to order and customisable to different tastes and body types in order to mitigate waste and embrace all, Veljanoska walks the talk.

Tiah Remeti, a shoe designer and founder of Esé London, which uses recycled leather, believes that a focus on quality over quantity can help shift both consumer and business perspectives on fashion. “My business ethos is women having staple pieces of footwear where they don’t have to compromise on comfort. I’ve found that we constantly buy high heels, and we might wear a pair once and never again because it’s uncomfortable. A movement towards functionality could help alleviate the overconsumption habits promoted by fast fashion.”

Though independent retailers and resellers are viable routes away from the fast fashion industry, all modes of consumption have a negative impact on the planet. The former path avoids a symptom of our collectively unhealthy buying habits but not the root cause: consumerist culture. As we head into the new year, we have the opportunity to reimagine ways of self-expression that aren’t so closely tied to how much of what we own and the hypnotic manner in which exploitation is sold to us – let’s take it.

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.