‘Music can move people to make change’: just how useful are climate concerts?

Music has a long history of mixing with social activism. Kimi Chaddah talks to organisers and artists to discuss whether concerts like Climate Live are a logical move for the environmental justice movement.

Kimi Chaddah

13 Nov 2021

Kevin Lake for Climate Live

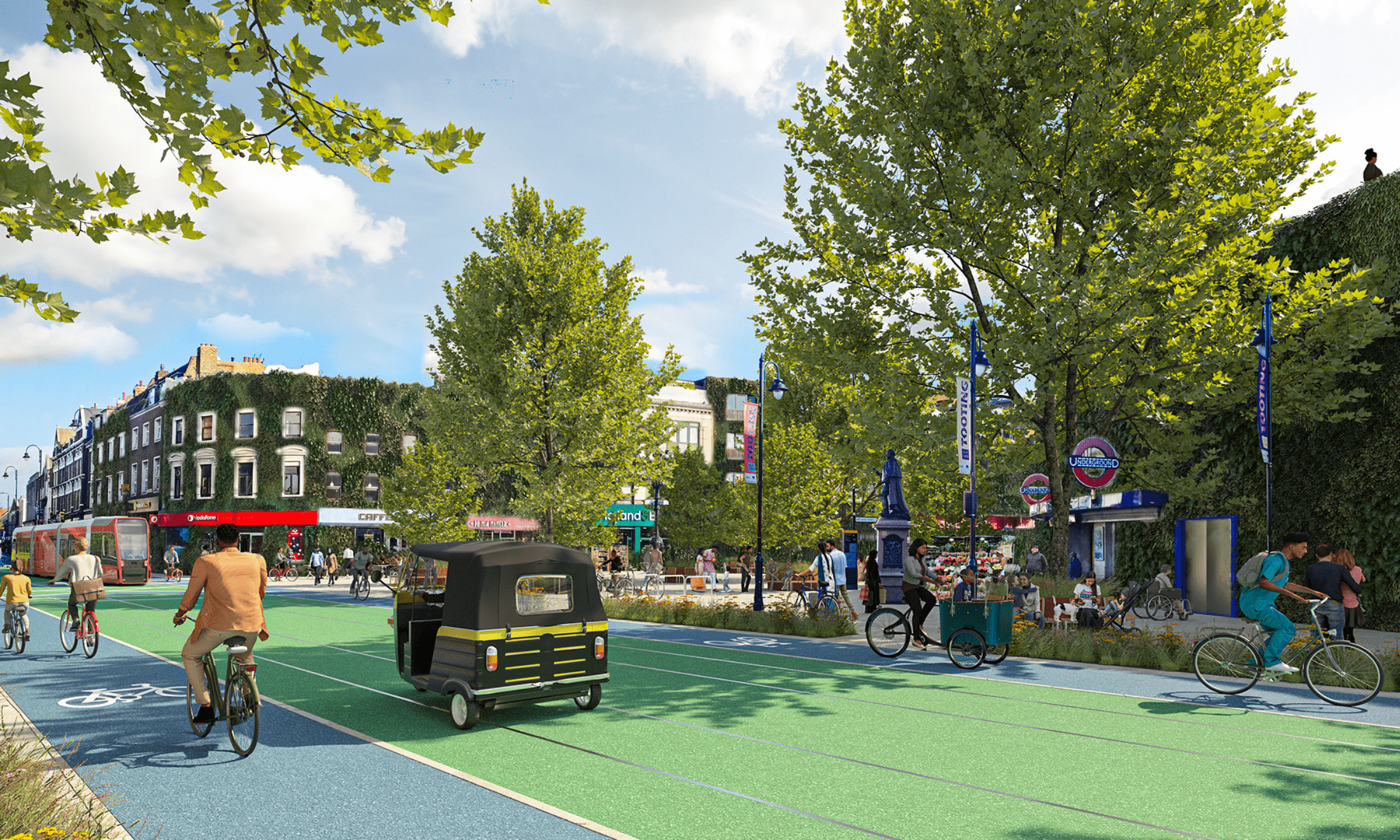

On November 6, the music radiating out of London Eye, Victoria Embankment and Camden Town represented more than a scheduled concert. With performances from Nova Twins, GIRLI and second thoughts, a growing crowd of people gathered around a vibrant open-topped bus.

This was part of Climate Live: a series of scheduled concerts over the past year aiming to engage and mobilise the masses in the climate crisis. Organised by activists and artists including Greta Thunberg, Sam Fender and Declan McKenna and supported by Greenpeace and WaterAid, a video of Thunberg “rickrolling” at the opening concert in Sweden gathered swathes of media coverage. With teams in 20 countries, Climate Live is one of many emerging movements aiming to galvanise large numbers of the public, using the cultural clout and advocacy power of artists to strive for tangible change.

To avoid actions contradictory to their message, each Climate Live team has a green action plan and awareness of their carbon footprint. Through the motto of ‘Engage. Educate. Empower’, Climate Live organisers want attendees to become invested in the crisis, feel empowered to tap into their local surroundings and place pressure on elites at the top.

Artists and activists are increasingly exploring the significance of music as a way of raising awareness of environmental injustice globally. By expressing hope and the need for direct action in different ways to tap into new audiences, Climate Live coincides with a shift in public attention towards the climate crisis to produce cultural and – eventually – systemic change. “We’re all fighting the same fight in varying ways, but at the end of the day, we all want climate justice,” says Rianka Gill, a Climate Live organiser based in London.

History of change

Events such as Climate Live – which use music as a way of drawing attention to issues of social justice – align with a history of music intertwining with protest, social commentary and radical change. In 1976, Rock Against Racism, a cultural and political movement gained traction in response to rising racist attacks in the UK, inflammatory statements from rock artists and increasing support for the far-right National Front. National carnivals, tours, local gigs and tours were organised over six years, with the aim of highlighting the struggle against racism through music. Nine years later, in 1985, Live Aid – a worldwide rock concert held in Wembley Stadium – raised £150 million for Ethiopian famine relief.

In a revival of expressions of resistance and desire for change, music became a soundtrack to political protest. Punk rock, which originated in the late 1960s, often had political, anti-establishment lyrics, expressing frustration at subjugation. Its legacy includes the Riot grrrl movement in the 1990s, which incorporated punk rock to amplify feminist concerns and centred bands like Bikini Kill as forces for empowerment in a male-centred industry.

Hip-hop, which began as an indictment of daily oppression and police violence in the 1980s and 1990s, has acted as a rallying point during Black Lives Matter protests. In New York City last summer, protesters chanted the hook to Ludacris’s 2001 song ‘Move B—’ when crowded by police officers on the Manhattan Bridge, reflecting how hip-hop continues to mobilise the masses against systems of oppression.

Now, festivals and musicians are incorporating climate concerns into their planning and performances, all-the-while fighting for social change. In 2019, the Californian festival Coachella offered prizes for those participating in Carpoolchella – an initiative that encourages people to ride with four or more people to limit carbon dioxide emissions.

Meanwhile Glastonbury is determinedly pursuing a greener agenda, and is intertwined with historical and political change. In 2019, the sale of single-use plastic water bottles was banned, with 800 taps installed to avoid the use of plastic water bottles. Extinction Rebellion’s high-profile protest at the festival in 2019, coupled with an evolving greener agenda, are marking a collective shift in the need to urgently confront the crisis and swaying festival-goers to shift their behaviour.

Potential criticism

At first glance, climate concerts sound oxymoronic. How can events consuming masses of electricity and fuel, which thrive off large audiences (and subsequently generate a large audience and artist footprint) possibly ‘go green’?

Holding concerts to avert the climate crisis may provoke accusations of hypocrisy – yet as we’ve seen this past month from the actions of Insulate Britain, climate activists are running out of ways to grasp people’s attention without being deemed dangerous and becoming mired in conflict. By subverting the conception of climate crisis as an issue confined to the media and science, and the perception of activists as disruptive and troublesome, growing initiatives like Climate Live aim to produce a cultural shift, breaking down the traditional walls surrounding the climate movement and inducing popular, global recognition of the work to be done.

“Music in itself might not change the world by itself, of course,” acknowledges Jon Bonifacio, a local organiser and education coordinator at Climate Live in the Philippines, “but it’s about moving people – motivating them to make that change.” With music, “it’s not going to be the only thing you’re doing; it’s not an ‘either/or’ – it’s an ‘and’ to reach audiences we don’t typically reach,” he adds.

The fight for indigenous people

Music is the lifeblood of the Philippines, artist Edge Uyanguren tells. Instruments such as bamboo buzzers, quill-shaped percussion tubes and flat gongs are used in the north, while ring flutes, log drums and xylophones are used in the south. Songs are laced throughout moments of happiness, such as festivities and celebrations, but also moments of tragedy. The Tubaw Collective, created in 2016, is an alternative music group with songs reflecting environmental themes, as well as the victories and struggles of the Filipino people. For the group, which Edge is a part of, Climate Live has also come to represent a subtle symbol of resistance and advocacy for indigenous people and the country’s most marginalised communities.

“Music in itself might not change the world by itself, of course… but it’s about moving people, motivating them to make that change”

John Bonifacio

Since 2012, the Philippines has remained one of the deadliest countries in the world for defenders of the environment and climate activists, according to an annual report by environmental human rights group Global Witness, who exist against the backdrop of a volatile political climate. “We need to defend the defenders,” says Edge, referring to both increasingly persecuted activists and indigenous people on the frontlines of protecting land, forests and livelihoods. While the Philippines is nowhere near the biggest emitter of greenhouse gases in the world, it is one of the hotspots of biodiversity, containing 75% of the world’s plant and animal species, home to the water buffalo (carabao), and 700 threatened species, including the endangered Philippine eagle.

Understanding the climate crisis as part of a larger social problem, the Tubaw Collective wants to place indigenous people’s plight and their quest for justice at the forefront. By raising awareness of the battles against the dominance of large-scale mining projects and the encroachment of large capitalist mining corporations on the land, the collective hopes to gather recognition that the climate crisis is deeply rooted in the exploitation of marginalised communities and the Global South.

“Construction is still ongoing, mining applications are still in place right now – there’s more corruption, there’s more harassment [of activists], it won’t stop,” says Edge, “and as long as it exists, we believe that we have a responsibility to do something about it.”It’s not that people don’t care about climate change, he says, but that there’s a lack of information about the issues. “The media doesn’t look at it, the documentaries are shown on late nights, so people don’t really have access to documentaries that talk about the current situation.”

With physical protest silenced, schools raided and freedoms once enjoyed now under attack as President Rodrigo Duterte continues with operations against activists, “Climate Live represents a different way of presenting our advocacy”, says Jon. “With physical protest, they shut you down, they’ll discredit you – but concerts? Not so much, yet.” The ‘yet’ holds a disquieting weight. With several governments making efforts to silence protest around the world, including here in the UK, concerts provide a different outlet to challenge oppression.

For the collective, then, Climate Live offers a platform to educate, empower and rally more support for the defenders being persecuted, indigenous people and farmers – all the while being consciously aware of the risk of being perceived to be challenging the prevailing status quo. But beneath the fight for justice is a celebration of indigenous people’s culture and lifestyle, explains Edge, with unconditional love and protection for the land underpinning their songs.

Socioeconomic divides

The lack of live shows due to Covid-19 restrictions, coupled with the economic fragility fuelled by the pandemic, has cast a shadow over the current batch of Climate Live concerts. Funding has been provided for the events (from a grant) – but for concerts that aim to raise awareness of social justice, the glaring socioeconomic divides between artists and their differing abilities to afford, host and organise events is lurking beneath the surface. While some are reliant on modern infrastructure and can solve touring logistics with relative ease, some struggle to make money locally from music and undeveloped infrastructure, rendering international touring inaccessible.

“Most of the performers [in the Philippines] don’t have the economic capacity to rehearse”, says Edge. “Running concerts is expensive – you have to pay for electricity; all these overhead expenses and turning to online platforms [which are free] is difficult”. As part of Concerned Artists of the Philippines – an organisation of writers, musicians, artists and cultural workers committed to the principles of freedom and justice, as well as resistance against oppression – however, the Tubaw Collective is able to receive funding, while working part-time has granted Edge with some semblance of financial stability.

Sustaining the momentum

With rising unrest over systemic inertia and the climate crisis, the growth of other initiatives, including Earth Percent and Music Declares Emergency (MDE), declaring a climate emergency is reflective of a cultural awakening. Established in July 2019, MDE is a group of artists, music industry professionals and organisations aiming to create change through music. MDE has partnered with Climate Live UK in solidarity, and recently launched a social media campaign, ‘No Music on a Dead Planet’. “One of the key reasons that MDE exists is that those of us who started it felt that there were many in music committed to taking action but they felt isolated”, says Lewis Jamieson, a spokesperson for MDE.

Of course, collective action needed to fight the climate crisis extends beyond individuals, social media campaigns, and one industry alone. “What we need now are systemic changes,” says Jamieson. “Addressing public transport massively reduces the footprint of audience travel, while better grid connections allow festivals to draw more clean power from mains”. Regional and national incentives are gathering pace too – they point to initiatives like cup recycling at shows in Germany. Colour-coded recycling bins are everywhere, labelled in German and English to encourage more people, including non-German speakers, to recycle.

Sustaining the momentum is going to be key in the climate movement over the next few years, as confronting systemic barriers to change risks becoming marred by indifference and inertia. But as these initiatives have shown, music transcends its traditional characterisation of a mindless distraction. Ultimately, its universal nature and ability to provide optimism and hope, perhaps more so than facts which induce despair, may prove vital in engaging the masses in the fight against the climate crisis.

For too long, both climate activism and climate coverage have overlooked the voices and experiences of communities of colour. Follow our new series, It’s Happening Now, for stories that look to change that.