Canva

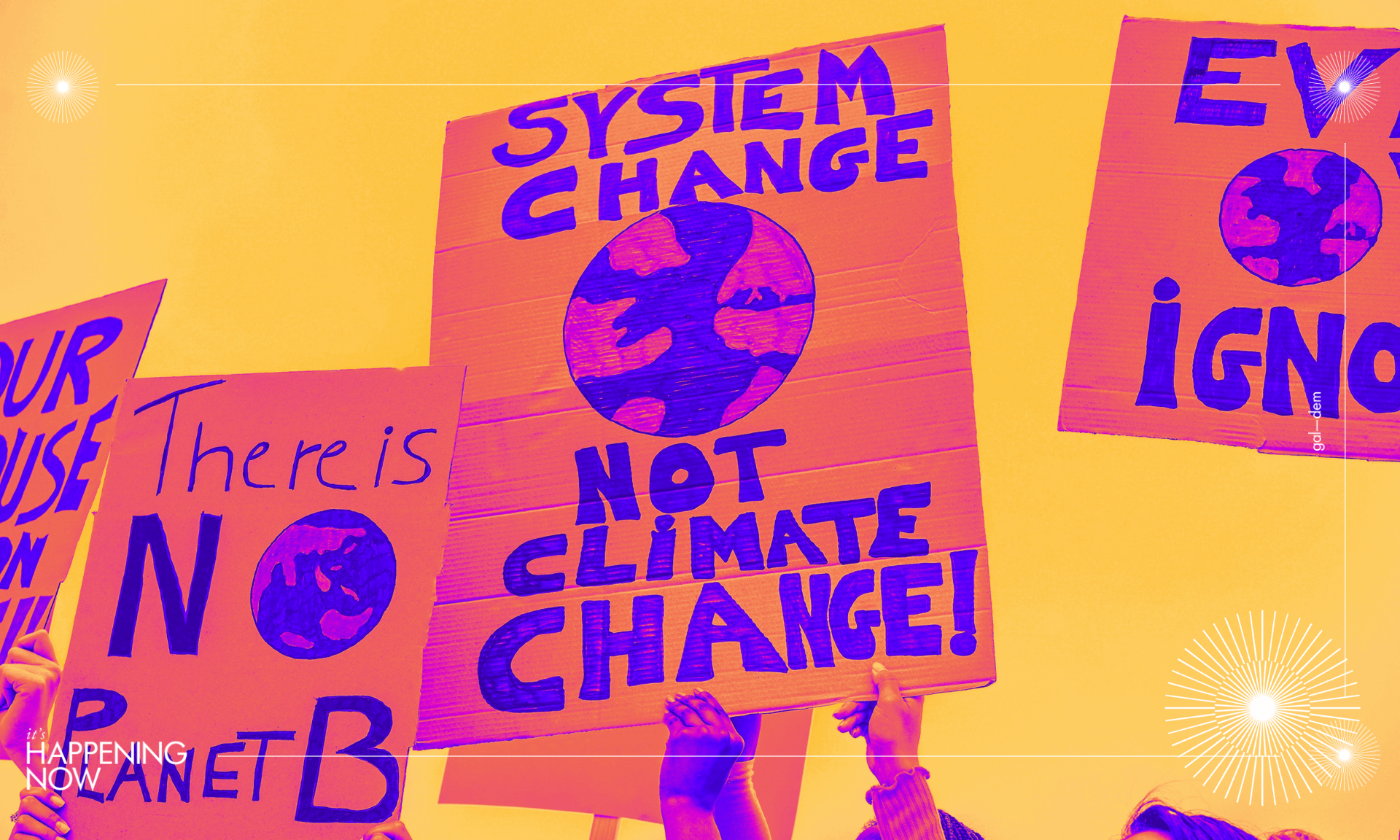

What sort of protest is necessary to fight the climate crisis?

Campaign group Insulate Britain have been blocking motorways and dividing opinion. But are they effective?

DiyoraShadijanova and Editors

18 Oct 2021

“Move out of the fucking way”, an angry mother inside a black SUV shouts. The woman’s school run has been blocked by climate protesters from the campaign group Insulate Britain. When the demonstrators don’t move an inch, the mother launches herself out of her car, screaming: “I’ll drive fucking through you then!”

This video made the rounds last week. It’s one of many clips captured by angry motorists in the wake of a – now suspended – controversial campaign of action by Insulate Britain. The group is relatively new and has a single-issue focus – to get the government to agree to a national programme that ensures all British homes are insulated by 2030, a key goal for ensuring the UK’s climate targets are met.

But their tactics have caused consternation. Insulate Britain’s method of choice is to block roads, seemingly wherever will cause the most chaos, with no discernment between the demographics they’re inconveniencing. It’s led to valid critique: that instead of organising carefully and systematically, to interrupt specific targets, like high-profile corporations (aka punching up), Insulate Britain focus on random individuals who happen to be driving down the road. Protestors seem less concerned about long-term, sustainable movement building and getting people onside – even those sympathetic with Insulate Britain’s cause think they’re too dogmatic in their approach.

So a question arises: how essential are disruptive protests to fight climate change? And just who should they be ‘disrupting’?

If you ask the home secretary, the answer to the former question is a firm ‘irrelevant’. Priti Patel has threatened to make disruptive protests more difficult by promising unlimited fines and six months of prison time for interfering with transport routes like roads, railways, along with newspaper printing presses. Patel also intends to give police wider stop and search powers specific to tactics regularly employed by environmental activists, by allowing officers to inspect activists for “lock on” equipment such as bike locks or glue and to specifically target people with a “history of disruption”, or those likely to commit a crime.

It’s usually a sure sign that if the home secretary strongly objects to a social justice campaign, it’s a force for progress. And it’s difficult to deny Insulate Britain’s achievements in the weeks they have been protesting. The group has brought the issue of insulating houses into the mainstream conversation around climate. Before the demonstrators started making headlines, did many of us even know that the UK has some of the oldest and leakiest buildings in Western Europe and that our households consume more gas than almost all of our neighbouring countries? Structural change, such as insulating our homes to reduce our dependence on gas to heat British homes, needs to happen fast, and the climate group wants as many people to be aware of this fact as possible to pressure the government into action.

Yet that’s not to say all disruptive protests are well thought out. As Insulate Britain’s roadside efforts intensify, so does the frequency of them making shortsighted decisions. Just recently the group was criticised for trapping a motorist travelling to see her elderly mother, who was being carried to a nearby hospital by ambulance. Road-blocking, though effective in enraging media outlets, will always risk being problematic on an individual basis. But is it possible to accept this and keep moving towards strategies that minimise these risks, without writing off disruptive protesting altogether? And is it also possible to recognise that one group’s disruptive protesting efforts are not a reflection of another’s?

“In my opinion, civil disobedience is the only way we’re going to make any progress in fighting the climate crisis”

Climate groups are understandably at a loss. If they don’t disrupt in a way that actually causes an issue, governments don’t listen to their demands as we collectively head towards ecological disaster. If they do disrupt the flow of society enough for people to take note, they inevitably end up hated anyway. In a losing game, sticking to your principles seems an obvious choice.

When it comes to the climate crisis, scientific research and the answers to our problems lay in front of us, but it seems that knowledge isn’t enough. ‘Peacefully’ protesting outside a government building or signing online petitions – only to get ignored by the same people who are preparing to approve another major oil field that will ensure the UK’s climate deadlines are missed – understandably feels like a complete waste of time. When climate concerns have been ignored for decades, people will resort to causing disruption out of desperation.

In my opinion, civil disobedience is the only way we’re going to make any progress in fighting the climate crisis. Not only do we know that historically, it works, but when it comes to the current environmental catastrophe, we’re also running out of options and time. Past and future greenhouse gas emissions are irreversible for millennia, especially changes in the ocean, ice sheets and global sea levels. We can’t just install a few windmills and solar panels and hope for the best. The most recent IPCC report confirms this: the 1.5°C limit of a relatively “safe” global temperature rise could well be reached by the 2030s – a whole decade earlier than experts previously thought.

Considering the status quo got us exactly to where we find ourselves now, we need to accept that the major systemic change needed to mitigate the worst of environmental destruction will be a clunky process. Regular disruption of the ‘daily grind’ until action is taken will form a big part of that.

The myth of the ‘perfect’ protester

Throughout history, the narrative of passive resistance has been idealised, and we’ve seen an active erasure of disruptive protest. When it comes to climate protesting specifically, perhaps we should challenge the concept of a ‘perfect’ protest or protester who causes maximum disruption to… absolutely no one. In reality, most criticisms of civil disobedience become great distraction techniques from the life-threatening issues at hand.

Historically, protesters the world over have also used disruptive techniques to achieve their goals. What did smashing windows have to do with fighting for women’s right to vote in 1912? Very little but the Suffragettes did it anyway (and were viewed similarly to Insulate Britain at the time, compared to their lionisation now). Besides, what is Insulate Britain meant to do? Start going into people’s houses – the site they’re campaigning to change – and protesting there? Can you imagine how much more counterproductive that would be?

What Insulate Britain needs to learn is how to channel their disruption. And there’s plenty of examples of climate protesters who are tactically smart: take the Tree Sitters of Pureora; a group of friends in New Zealand who in 1978 set up home in the branches of thousand-year-old native trees in order to protect them. Or the group of protesters who in 2016 stopped the Otter Creek coal mine, one of the largest proposed in America, by using their bodies to block coal trains. There are also the many indigenous groups across South and North America who have been protesting energy companies destroying their lands for pipelines for decades. Just a few weeks ago 200 indigenous Peruvians took control of the Petroperu pipeline, which transports crude oil to a refinery on the Pacific coast.

What we shouldn’t do is tar all climate protesters with the same brush if the execution of one group is a little off. Sometimes disruption is successful and sometimes it isn’t, but expecting perfection from all protests, ever, doesn’t make space for collective learning from past mistakes. And that’s what’s needed in order to build stronger coalitions in the fight against the climate crisis.

People also love going in on the fact that many visible climate activists in the West are white and middle-class, meaning they’ve (supposedly) got less to fear from the threat of arrest as a result of protesting. It’s true that some protesters are far more marginalised and may not be able to risk being as disruptive, but what then is the alternative to disruptive protests mainly carried out by people with so-called ‘privileges’? That no one protests until society is completely equal? Or should we push those with more to lose from engaging with the police onto the frontline? Just like there will never be a perfect protest, there will never be a perfect protester.

“Disruptive protesters might piss people off but it’s becoming abundantly clear that they’re only there because we’re running out of ways of fighting the climate crisis”

Equally, there are fears that disruptive climate protests may feed into extremist concepts like eco-fascism – a totalitarian, white supremacist approach to the climate crisis in which individuals sacrifice their own interests to the “organic whole of nature” and climate issues are blamed on things like overpopulation, immigration, and over-industrialisation.

However, while eco-fascism has been linked with mass-shootings and terrorist attacks, the violent solutions offered by its ideology, such as “population control” are simply miles away from the climate protesters laying down in the middle of the road in a desperate plea for the government to insulate some houses. Conflating freedom of expression with extremism is just another diversion tactic used by those with vested interests.

Constructively calling out climate groups for their lack of diversity and Western-centric narratives shouldn’t deter us from fighting for the same political policies that would structurally benefit us all. The more we expend all our energy on these surface-level debates, the more we lose sight of the burning planet, which frankly doesn’t care about ‘privilege Olympics’.

Disruptive protesting will never be perfect, but in the end, it becomes a trade-off of short term frustration vs. long term disaster. It’s okay if you’re angry because you just need to get to work on time, or your dinner plans have been ruined. But those who claim that a single act of civil disobedience has put them off fighting against the climate crisis may want to reconsider. Disruptive protesters might piss people off but it’s becoming abundantly clear that they’re only there because we’re running out of ways of fighting the climate crisis.

For too long, both climate activism and climate coverage have overlooked the voices and experiences of communities of colour. Follow our new series, It’s Happening Now, for stories that look to change that.