What does the changing face of cosmetic surgeries tell us about desirability?

Trends come and go, but when they're based on the natural features of people of colour, there's lots of complications.

Parisa Hashempour

23 Mar 2022

illustration by intranetgirl

When Kim Kardashian first ascended to celebrity royalty – her curvy, hourglass figure rose along with her – 27-year-old Indian-Iranian Brit, Leila, felt empowered. With a similar body type to Kim, it wasn’t long before Leila felt the vibrations in her own life. “Suddenly I could go to a bar and get attention,” she explains. “It was really validating to feel seen like that.”

By the 2010s, the new face of beauty had arrived, offering an alternative to the slim, blonde, big-breasted beauty icons who seemed to rule the 00s (think Jessica Simpson and Britney Spears). This new face, and the body that came with it, carried many of the features of some women of colour. Jennifer Lopez, Priyanka Chopra and Lupita Nyong’o sat atop the ‘world’s most beautiful women’ lists, and 2015 became the “year of the rear”. Already popular in Brazil, it was at this time that BBLs (Brazilian butt lifts) sprang into public consciousness, and low-cost lip and cheek fillers and implants went mainstream.

Much like Leila, I was at first heady with my newfound visibility. The embarrassingly wide hips cursed upon me by my Iranian ancestors transformed miraculously into a blessing, and TV shows like Scrubs that told me my bum should NOT ‘look big in this’ made way to the Nicki Minaj lyrics that suggested it should. Long gone were the evenings spent Googling ‘buccal fat removal surgeries’, to rid myself of my full cheeks, and instead, I was left wondering if I should get filler. But trends, by their nature, come and go. And with Y2K fashion’s recent rebirth and rumours the Kardashians have removed their BBLs (or at least made them smaller), I was suddenly left asking — am I going out of fashion too?

“I was left wondering who gets to feel desirable and when, and what exactly is driving these trends?”

This was something that played on Leila’s mind, too. “I feel like I’m getting into the same mental space as when I was 18,” she told me, directing me to TikTok where a whole host of South Asian and Middle Eastern women describe themselves as having ‘2016 face’. Their naturally big brows, fuller lips and cheeks were trending six years ago, but today have been replaced with a post-Glossier, fresh-faced look that those like Arab-Canadian TikToker, Bamblie, are finding hard to replicate: “It doesn’t matter how hard I try to achieve the natural, dewy, makeup, slicked-back hair, clean look, I always look like I’m straight from 2016,” she says in a video.

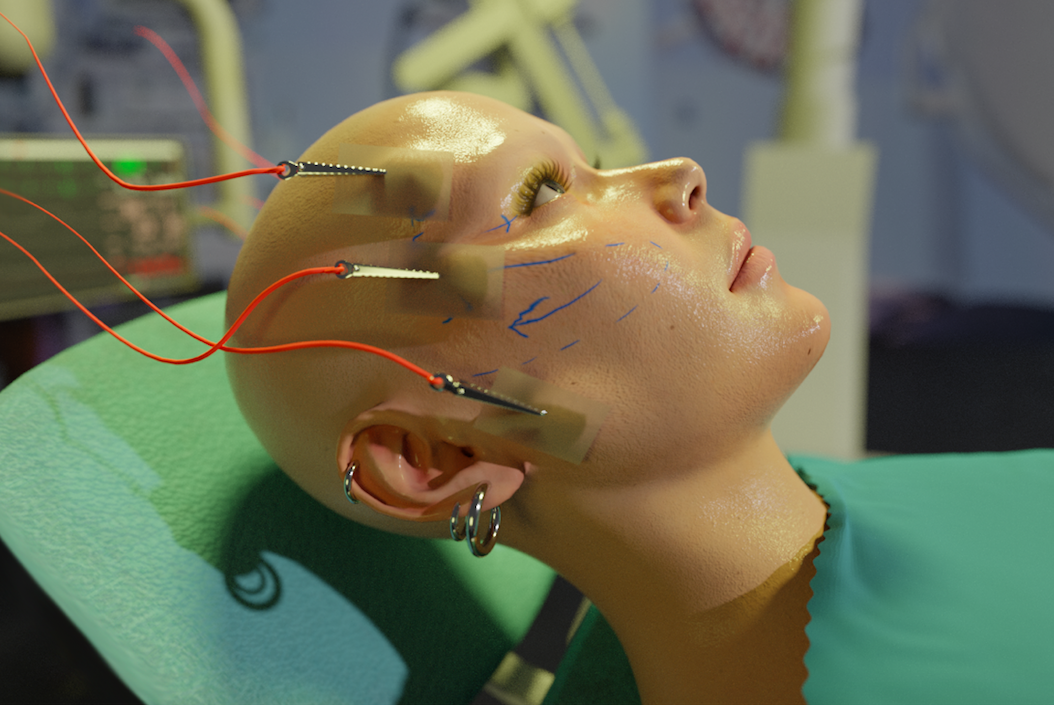

But something didn’t quite add up. From lip and cheek fillers and BBLs to the newly popular ‘fox eye’ procedure, which uses sutures to create an almond eye shape described as appropriating East and South East Asian people, surgeries influenced by racialised features dubbed ‘exotic’ aren’t going anywhere. So what is going on? I was left wondering who gets to feel desirable and when, and what exactly is driving these trends. But most importantly, I was left asking where they leave the women whose features are being recycled in and out of fashion faster than a pair of flares.

The aesthetic industry is booming

According to aestheticians, threadlift procedures (an alternative to invasive facelift procedures) are at an all-time high. Though there are no official statistics, data seen by gal-dem from clinics like Essex’s Vie Aesthetics have seen the number of ‘fox eye’ threadlifts more than triple since 2019 along with tear trough procedures. The Harley Medical Group has also seen tummy tucks grow by 18% in the last year and rhinoplasty (nose jobs) increase by 8%. Non-surgical rhinoplasty has made the procedure easier, and in the past year, Vie Aesthetics has seen a 19% increase.

Even BBLs, speculated as on their way ‘out’, are projected to rise thanks to new safety-improving technologies. Dr Omar Tillo, a cosmetic surgeon and founder of Westminster’s CREO Clinic, predicts gluteal lipofilling (fat transfer to hips and buttock) will overtake breast augmentation — consistently the most popular procedure — in under 10 years. Before the pandemic, he reasons, “the American Association of Aesthetic and Plastic Surgeons showed BBLs growing 20% year-on-year.” Unlike the more dangerous BBLs of the past, which might involve liposuction of your entire body, these new procedures remove the fat tissue from the bum’s surrounding areas and then inject it superficially over the gluteal muscle. “It’s the safer way of doing the procedure, and it’s about performing that natural look rather than the exaggerated look,” says Dr Tillo.

“Knowing that white women want and pay money for all the shit I naturally have does validate me”

Cristina

Through surgeries like these, the features found naturally in some women of colour soon became signifiers of beauty and, as such, they became assets. But when a body part holds value — and can be co-opted as fast as a lunch break walk-in procedure — I wondered if it might create more disparities than it disperses and, crucially, whether it maintains a higher value on white women. Cristina, a 21-year-old student with mixed Moldovan and Nigerian heritage, feels conflicted. While she worries fashions exacerbate the hyper-sexualisation of Black women, she also says, “I used to long for straight hair and skinny thighs, but now I love my Blackness. Knowing that white women want and pay money for all the shit I naturally have does validate me, and it definitely gives me a sense of pride.”

One such woman is 31-year-old Isabella James, an influencer and glamour model who regularly has lip, face and nose filler as well as Botox. She has had a number of invasive surgeries including a ‘supercharged BBL’ as well as three breast augmentations including ‘XXL implants’. Last year Isabella doubled her OnlyFans income, now earning around £75,000 a month, which she attributes both to spending more time on her business and her latest implants. When questioned on the implications of having lip fillers and a BBL as a white woman, she explains she had never correlated them to anything other than the “blonde bimbo” look of her industry.

Though admitting she now sees the link, Isabella told gal-dem, “I don’t look like a woman of colour whatsoever. I look like a white girl with a big fake butt,” — and why would she have given it further thought? As an entrepreneurial white woman, self-professed as someone who stays away from the news and likely seldom has to think about race, surgeries and filler top-ups are, for Isabella, a business investment and a way to play with her look that has filtered down through popular culture. It’s a culture that idolises specific, changing and unattainable ideals and so, in a sense, she is profiting from a system that most often works to undermine women. But these surgeries are harming more than women’s purses, particularly for women of colour. While for Isabella, there is no ill intent in electing for these procedures, she makes a crucial point — no matter what she has ‘done’, she will always look like a white woman. So where does this leave the Black women whose features might be said to have been emulated?

The impact on women of colour

“People ultimately can do what they want with their bodies. It is their choice. But, it is so deeply frustrating as a Black woman to see how these features are desired and prized on white bodies, but seen as undesirable on Black bodies,” says 29-year-old Angolan and African-American Co-Director of We Are Here Scotland CIC, Briana Pegado. While Saartjie Baartman, a South African woman living in the 1800s, was tortured, caged and humiliated for her curves and bottom by white people, it is little wonder that women such as Briana see surgical trends trying to achieve a curvy shape today as frustrating.

Desired for their sex appeal, the fetishism behind the ‘fox eye’ procedure trend may present similar problems. Professor Nishime, a scholar specialising in Asian-American media representations explains, “I don’t see many people getting surgery on their noses, even though East Asian people have a differently shaped nose,” adding that “for East Asians, what gets fetishised [by other people] is [their] eye shape.”

This is something 29-year-old British-Chinese content creator and writer Amy Lo has found hard to come to terms with. Growing up, Amy would watch YouTube videos on how to make her eyes look more round, applying white eyeliner to her waterline to create a rounded appearance. “I feel annoyed and frustrated that my eye shape is ‘fashionable’ and people even turn to surgery to achieve it. I’ve had this facial feature my whole life, but would be made fun of for it growing up,” she says, adding that it only seems to be desirable if it isn’t on an East Asian or South East Asian person.

“I feel annoyed and frustrated that my eye shape is ‘fashionable’ and people even turn to surgery to achieve it”

Amy Lo

Despite this, these trends are not only appealing to white women, but to women of colour too. When she first came across the ‘fox eye’ trend in its infancy on TikTok — then the ‘fox eye’ makeup trend, the surgical treatment’s precursor — Amy says she was admittedly drawn to it. “I wanted to try it myself as I thought it would suit my eye shape more,” she says, adding, “Now I realise I probably thought it looked nice as the makeup reminded me of my own eyes.” This points to the fact that even women who supposedly have ‘trending’ features naturally are not immune to changing fashions. Similarly, in Dr Tillo’s clinic, most women coming in for surgery to create an “hourglass figure” have Afro-Caribbean and Middle Eastern heritage. While CREO Clinic pride themselves on embracing the ‘natural look’, the aesthetic that many women pursue through BBLs creates a shape “not typically found in nature”, as video essayist Khadija Mbowe notes in The Rise of The Slim-thick Influencer. They remind us that some women of colour, who should supposedly have these idealised features naturally, simply don’t. As such, they will always feel unattainable outside of surgery.

The pressure on women of colour to reach the ideal can be high; this is something Black-British influencer, Renee Donaldson, has been outspoken about. After building her business online, she felt the urge to get a BBL, aged 24. “There is a lot of pressure to look a certain way to get the best-paid collaborations online,” she told Metro. But the surgery was unsuccessful. Resulting in lumps and a bulge on her thigh, Renee required two corrective procedures and has since issued an apology for encouraging her followers, saying “I’m tired of going to hospital, I’m tired of being on painkillers, I’m tired of feeling like this.” When carried out by underqualified surgeons or aestheticians, procedures often come at a hefty physical and financial cost. Isabella spent $5,000 dissolving lip fillers that ‘blew out’ the shape of her lips. But worse than that, surgeries can even be fatal, with some estimates saying one in 3,000 BBLs result in death.

Understanding trends in surgery

I was left wondering where these trends come from in the first place, and why they take such a hold on us – both white women and women of colour, even if they sometimes come at extreme costs. I asked Professor Nishime for some clarity, and she chalked it up to a mix of politics, culture and the social moment we find ourselves in. But for her, it was also, in many ways, a clear-cut case of appropriation. She stressed that while embraced by both white women and women of colour, these trends signified different things on different bodies.

Bridging the ‘fox eye’ trend of today with the 1800s, a time when wealthy house-bound white women purchased kimonos and interior decorations from the ‘Far East’, Professor Nishime explains: “When a westerner sees an East Asian woman in a kimono, it’s about tradition, being submissive… but when you see a white woman in a kimono, it’s about their worldliness.” Similarly, she explains that ‘fox eyes’, BBLs and other cosmetic surgeries might act as a form of “cultural capital” for white women today. “Part of that capital comes from still being recognised as a white woman,” — much like Isabella, who rather than embrace worldliness, displays a degree of status through her obviously done procedures.

“it’s conditional; it’s dependent on your proximity to whiteness”

Natalie Morris

In the UK today, I noticed how this parallels with the ethnically ambiguous mixed-race beauty plastered across adverts and social media and the power that can come from proximity to whiteness. Even for these women, shifting ideas of beauty and the idolising of an ethnically ambiguous aesthetic is a point of anxiety due to the fact they have no control over the way beauty trends change. This is something that Natalie Morris, British-Jamaican author of Mixed/Other: Explorations of Multiraciality in Britain, has touched on in her work. She explains that this idea of beauty is, “something that’s really destabilising in terms of your self-worth. You’re constantly re-evaluating how you are being perceived.”

With many features found naturally on women of colour still battled against in the name of beauty, what remains implicit when we venerate an ambiguous look is that “it’s conditional; it’s dependent on your proximity to whiteness,” Natalie tells gal-dem. As trends move on, this will likely remain the same — even if the racialised feature whiteness is paired with changes.

What’s next?

It doesn’t feel like the quickening rate of changing beauty standards is about to stop any time soon, and according to Professor Nishime, these trends will keep rising and falling. But, of course, none of this takes place at the individual level, and as Natalie puts it, “this isn’t a problem to be levelling at a random woman who has gotten lip fillers.” And this is part of the issue; there isn’t one person we can level our concerns at. Even social media influencers like Renee and Isabella who initially help to spread these trends are victims of them too.

Rationally, I know that for as long as our worth as women is dependent upon our looks, our physical, financial and mental health will always be ready to take a bruising. I also know that until we stop looking to the norms set out by the dominant white culture to measure our desirability as women of colour, our self-esteem will always be teetering on a precarious cliff edge, too.

But despite all this, I cannot pull myself away from aesthetician’s Instagram pages or help but fall prey to any clickbaity celebrity surgical ‘before and after’ that shows up on my newsfeed. As someone who often had no control over how I was viewed by others growing up, I can see how the promise of surgery and fillers offers a tempting chance to take control back and remake yourself. Let’s not forget, beauty and fashion culture is also fun — from post-Covid-19 dopamine dressing to the ear stretchers worn by the Ancient Brits before the Roman invasion, decorating our bodies is an intrinsically human act and cultural borrowing is as old as antiquity. But are body parts really for borrowing? Or does that intrinsically cause harm? With more questions still than answers, I’m left reflecting on Professor Nishime’s warning that appreciation, at its root, is about commodification; we are buying and selling in racialised features. Commodities, which are easily stripped of value at any time, have a shelf life. That means there’s an expiry date on our trending features, too.