Reboots, remakes and homages – why is everything the same?

Music performances, television, films and fashion right now are filled with nostalgia. Where's the originality?

Moya Lothian McLean

17 Sep 2021

Instagram/YouTube

Watching pictures flood in from the VMAs red carpet this weekend, I had one thought: we need to call a moratorium on the ‘homage’. Ditto the ‘reboot’. Let’s even go so far as to press pause on the ‘reference’ until Hollywood and its assorted stars can stop misusing the term so violently that we have to see a Z-list internet personality wearing one of Beyoncé’s cast offs in the hope of snatching some camera time.

Originality is an alien concept in Western entertainment at the moment. Film, TV and music audiences are being told to subsist on a non-stop diet of remakes, re-imaginings and remixes. From Friends to Candyman, it seems like the only way to garner a green light on a project is by piggybacking on a previous work – even if it means dragging an ageing and reluctant cast back to ruin its legacy.

Music videos and performances are stuffed full of baton-passing cameos and ‘references’; red carpets see new starlets trotting out old clothes, worn by icons before them. Samples are du jour in tracks given to those on the cusp of stardom. None of this would be a problem except sadly, it’s all very fucking boring.

Nostalgia consumption isn’t anything new but we’re currently in overdrive. It’s not gone unnoticed; myriad essays exist unpicking the reasoning behind a ‘Gen Z’ driven desire to return to the cultural landmarks of the 1990s and ‘Y2K’. Explanations given include speculation that our future is in such jeopardy right now we can’t even bring ourselves to be ‘futuristic’ and instead want to return to the comfort of the last true period of pre-internet innocence. Or, suggests another, it’s because people have a longing for the “monoculture”, the idea that “we had a set of cultural texts that we all were familiar with” (debatable). Likely, there is also a degree of ‘chicken vs egg’ at play; we see nostalgic consumption and referencing everywhere so further reproduce that. Only now we are starting to run out of the recent past to consume, recycling outfits, songs and films that first came into being less than 20 years ago.

“Nostalgia consumption isn’t anything new but we’re currently in overdrive”

If this practice was resulting in cultural products that pushed conversation and creativity forwards, then so be it. Instead it seems more about making a quick buck, or grabbing attention. Many reboots seem rushed or lacklustre – see the reception of the much-hyped Candyman which critics agreed failed to deliver on its promise, and instead served up something “soulless” and “sanded off”, which felt a crushing disappointment given the wealth of Black talent involved.

Then there’s the ‘homages’ that litter pop culture but are invoked without any context or apparent reason to justify them. Why, for example, was influencer Bretman Rock wearing a Robert Cavalli dress to the 2021 VMAs that Aaliyah had first debuted on the same red carpet 21 years previously? He looked very pretty. But was the reason, the purpose anything beyond simply ‘getting into the headlines’? There was no weight to the gesture because Rock has no notable links to Aaliyah, the music industry or Cavalli, really.

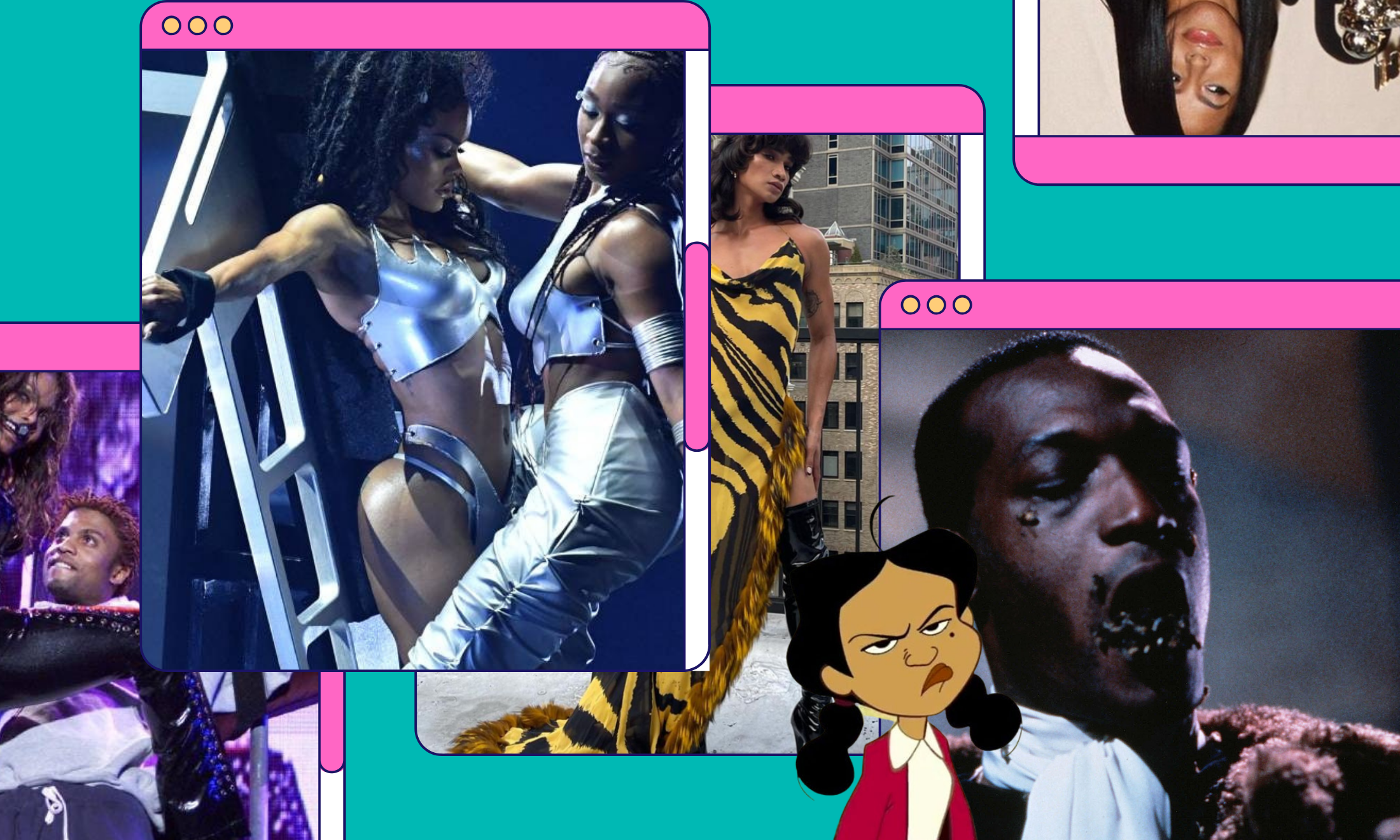

Meanwhile, rising stars Normani and Chloe Bailey both performed at the same awards show, their slots peppered with ‘references’ to Janet Jackson, Aaliyah (again) and Beyoncé. It’s understandable – admirable even – that two young Black stars on the rise will occasionally pay tribute to those who have come before.

But after a while, the constant ‘homages’ become all there is, overshadowing their own identities as performers. What do these new stars have to add to the cultural lexicon for generations to come? What will they be remembered for? The only stars at the VMAs who seemed to carve out an unmistakably original space were reliable weirdo Doja Cat, at one point dressed as a worm, and Lil Nas X.

And there’s one more nagging aspect; it’s not hard to notice how much of this cultural consumption seems dedicated to recycling and reusing the work of people of colour – often Black – in a manner that seems designed to do the work of ‘diversifying’ without actually… doing that work. Celebrating and revisiting the past work of people of colour under the guise that it was overlooked (which isn’t always accurate, let’s be real) is great, but it can sometimes seem like a stunt without the action to make long-term industry change backing it up.

“It’s not hard to notice how much of this cultural consumption seems dedicated to recycling and reusing the work of people of colour – often Black”

Take the planned revival of The Proud Family, rumoured to feature the likes of Lil Nas X and Lizzo as marquee names. Ok, cool. But what if – and this is a wild idea – Disney funded another, new cartoon featuring a predominantly Black cast and hired fresh talent, not existing celebrities, to star? Or instead of Universal doing a gritty “reimagining’ of the Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, the cash goes towards a whole new series instead? Ditto reboots that take previously ‘white’ films and stick Black leads in them. Is it really giving what they think it is?

The desire for the new is out there; when fresh ideas do manage to burst to the surface, their success is often so great that carbon copies begin to emerge within months. Jordan Peele’s Get Out was so radically exciting in 2017 that it’s already spawned a host of imitations (and a reckoning about what a loaded genre like ‘Black horror’ should stand for). It’s not to say that the cultural recycling has to disappear forever – otherwise we wouldn’t have the likes of Into the Spiderverse. But for the sake of the hot young things of the future, who won’t have anything to reference if we keep up this pace of cultural cannibalisation, can we please get some originality back?