YouTube / Disruptive Records

The song ‘Global Jatt’ is a reminder of Bhangra’s issue with casteism

The popularity of tracks like 'Global Jatt' is an insight into how pervasive casteism is within our culture.

Aman K Soomal

17 Mar 2021

Earlier this month, a music video called ‘Global Jatt’ was released by Bhangra artists Bups Saggu, Jatt Life and DJ Kam Kang. When I first heard the song, I sat in shock for a full few minutes, trying to process its content.

The video appears to cater to those who live the upper caste Jatt “high life”, driving Lamborghinis and drinking alcohol. It was made in collaboration with an alcohol brand called Jatt Life Global, and the depiction of drinking itself is harmful, given excess alcohol consumption and domestic violence are known problems within our community. The video also shows white women (“goriyas”) chasing after them, because they are Jatt. I was incredulous as to what the intentions were.

In Sarah Sahim’s essay in The Good Immigrant, caste is described as “an ancient and complex social stratification system with Dalits (Marathi for “oppressed”) at the very bottom and Brahmins – the spiritual and scholarly class – at the top”. Although this definition applies to Hindus, the caste system is also found in families who follow Sikhism and Islam. Punjabi Sikh families may consider Jatts and Tharkhans as the upper castes, while all others are considered lower castes and Dalits. In plenty of popular culture, music and movies, the word “Jatt” is thrown around with no thought of the impact it would have on people who don’t identify with the caste.

I’m always intrigued by narratives and the language that people use to describe their life experiences. So what narratives ran through their mind when writing this song? What words did they feel were best to describe their experience of being born into upper caste families? What did they want to portray to the world about being born Jatt?

Within an hour I had written an open letter to the above parties and posted it on my Instagram. It was written from a space of vulnerability and my own shame. I chose to introspect and examine the beliefs and privileges I hold as a British Sikh Jatt woman. In the past I have been guilty of Jatt superiority, which I find abhorrent now. The letter appears to have resonated with many, who also were shocked at the blatant display of casteism within the song.

“How can people not see that ‘Jatt’ and ‘white’ are synonymous – and if the song was called ‘Global White’, there would be more than a few raised eyebrows”

In a world where the South Asian diaspora has been shouting Black Lives Matter, protesting for equality and against white privileges, it confounds me that people still subscribe to a caste system based on making others feel inferior, and themselves superior. How can people not see that ‘Jatt’ and ‘white’ are synonymous – and if the song was called ‘Global White’, there would be more than a few raised eyebrows. In the same way that Dalit movements have historically found solidarity with Black movements, we have to recognise that within South Asian hierarchies to be upper caste is to occupy a similar space to whiteness – not least because casteism and colourism go hand in hand.

However, the caste system is so embedded into South Asian culture that these terms are accepted. BBC Asian Network presenters and renowned DJs lauded the video, praising the writers on their creativity, posting fire emojis on their posts, reinforcing that casteism is simply the norm.

‘Global Jatt’ is not the only Bhangra song that makes explicit reference to caste in its title. Currently the song ‘Jatt te Tawani’ by Dilpreet Dhillon sits at Number 5 in the UK Asian Music Charts. Songs like ‘Putt Jattan De’, ‘Jatt Fire Karda’, ‘Jatt da Muqabla’ and countless others have had international success and are played at family events, in restaurants and on TV and radio channels. Though the conversation crops up, there is ultimately very little dialogue about the discomfort this may cause for people who do not identify with the Jatt caste.

Bups Saggu faced much criticism on his Instagram page, in response to which he deleted comments and blocked many critics. He denied that caste was an issue, saying it was “just a song”. I wonder if it’s just a song to those that “Jatt” does not apply to. When we subscribe to systems of race and caste, which many say does not exist in the Sikh religion (intentions and actions are very different things), we become the oppressors.

“Bups Saggu has denied that caste was an issue, saying it was ‘just a song’. I wonder if it is just a song to those that ‘Jatt’ does not apply to”

In these past few months, I’ve found it difficult to watch the trend of upper caste men and women supporting the Dalit community when it suited them, and when it looked good on their social media platforms. It didn’t escape me that a significant part of my social network who identify as Punjabi Sikh and Jatt posted #FreeNodeepKaur daily and wrote heartfelt captions in support of the release of the Dalit activist who was jailed, brutalised and sexually assaulted by police at the Farmers Protests Sites. However, the same people who like and comment on my every individual post did not engage with my open letter to eradicate casteism. In what context did Nodeep’s life matter to them? Does it occur to people from upper castes that caste was a significant factor in her arrest and subsequent treatment? What caste the police officers belonged to who would have hurt her, and what words related to caste she would have heard over and over again in her time in jail?

My intentions are not to shame others. When people are shamed, they stop speaking, but their beliefs remain intact and in some cases, may become stronger. When we speak to others with compassion and love, and ask open questions, it allows them space to consider a new perspective. I can only hope that those who subscribe to the caste system can see how damaging it is to themselves and others, and how the content they absorb daily – even a seemingly harmless Bhangra song – can maintain that division between society.

The Gulabi Gang is a sisterhood fighting against domestic violence in India

After a gruelling year of heatwaves and floods, Indian climate groups get to work

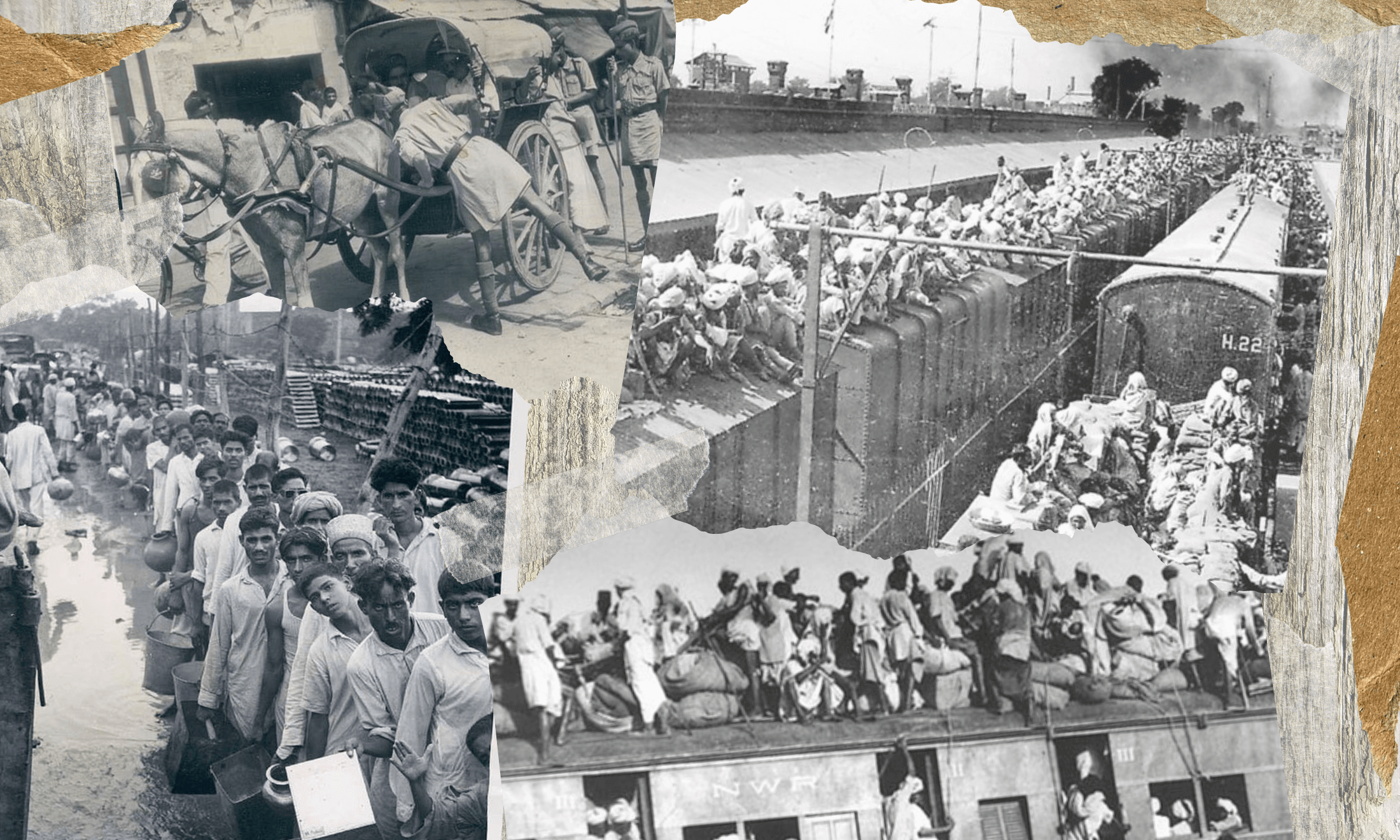

‘The other side’: Remembering Partition 75 years on