Hey, teachers, leave them kids alone: the struggle to recognise prejudice in school

Varaidzo

24 May 2016

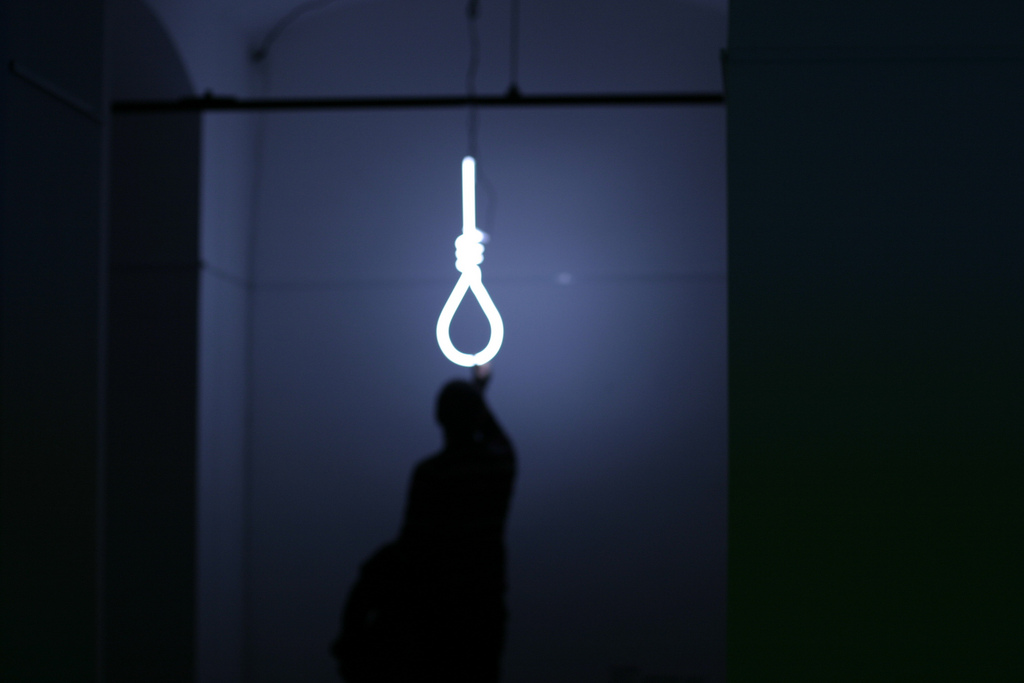

What do you do when you send your child on a school camping trip and they return home with deep rope burns around their neck? Whose story do you believe: your child’s, or the responsible adults in charge?

This is what happened to Sandy Rougely, a mother from Texas. Her child claims that she and other children had been playing with a rope swing when she stopped to watch. Next, she felt the rope around her neck, and she was tugged backwards. “None of the students helped her,” The Dallas Morning News reports Rougely saying, and “small pieces of rope were embedded in her neck.” The girl thinks it was three boys who had been picking on her who were responsible.

When I saw the pictures of the burns around the girl’s neck, it disturbed me. It gave me shivers, invoking images of noose burns and, in particular, the aftermath of lynchings. Why? Because the little girl is black, one of only four black people in her school, and the little boys in question are white. From the details given by the girl, the incident does seem to have the markings of a racist attack. But the school says that her injuries were “caused accidentally”. So, just who is a parent to believe?

As children, we are taught to obey and respect our teachers. As adults, it’s easy to feel sympathy for teachers, having to both control and educate an entire classroom of children. It doesn’t take much rationalising to believe a teacher over a pupil. Yet, now that I’m an adult, I look back on childhood incidents where my frustrations had been postured as my own fault and realise the lines aren’t so clear.

Some of the most traumatising of these incidents took place on long-stay trips away from home. At nine-years-old, on a week long trip to an activity centre, I remember a teacher marching me to the bathroom to wash my mouth out with soap because she had overheard me spelling out a swear word to my friend. She stood over me by the sink, refusing to let me leave until the soap was in my hands and was about to reach my lips. It was only then that I could stop. The punishment was over, and I was made to feel thankful that it didn’t actually touch my tongue.

On another trip, aged 10, I thought I’d started my period because the lining of my swimsuit turned red when wet. I told a teacher and as she was also a mother of a child in my year I thought I could trust her. Instead, she got frustrated at me when I “wasn’t sure”, urged me to be thankful she’d bought my sanitary products, and then told another girl in my year that I was emotional because I was menstruating. The news spread, and when I actually started my period I felt like I couldn’t tell anyone, not even my mother. I cried immensely. It was hell.

In both instances, my mother had trusted my teachers to look after me in place of her, to discipline me justly and look after me aptly. I trusted that this is what my teachers would do as well, and when both instances left me feeling angry and embarrassed, I’d assumed those feelings were my fault. The teachers knew best. I only had myself to blame.

It’s been so long since that I can’t gauge whether these instances were the result of simply bad teaching, or whether my race had something to do with it. I was the only black child in my year, and though at the time I never attributed it to my race, I do remember a distinct and pervasive feeling that teachers treated me far more harshly than my friends.

“At my school they’d always cast the black kids as animals in plays,” Olivia, 22, tells me. “All of us black girls were talking about how the teachers were racist but I think we got told off.” I’ve been trying to explore how incidents of childhood racism are handled in schools, but in many of the recounts of those I’ve asked it’s the teachers who do the most damage.

“During auditions for our Year 6 musical I overhead the music teacher discussing how the part for Annie should go to a white girl,” says Meena, 21, and Xena, 22, recalls how a teacher told her “there isn’t a problem here”, when another pupil was goading her by calling her brown, because “it’s true.” In fact, the responses brought out stories from all through the education system, from nursery to university, of teachers saying things or acting in ways that were racially insensitive.

Joanna, 23, was asked by her year 9 teacher whether she “ate everything with chopsticks at home”. Simran, 21, was told by a lecturer that he “wouldn’t expect girls of ‘asiatic backgrounds’ to go to the pub”. And, as Meena experienced, when she highlighted in a lecture how she found something to be racist, it was dismissed with, “maybe they don’t mean it that way, they’re just curious”.

“I had a dinner lady say to me and a friend ‘this is why I don’t like black kids’,” says Shanice, 23. “We told one of the other teachers and I’m not sure what happened after that but the same dinner lady then kept me and the friend in all lunch time and questioned us about it as if we lied.”

The recurring theme seems to be that children who question the racism and prejudice they experience around them are lying. Then, for that, they are punished or told off. And when it has been enforced through the school systems that teachers are always right, when parents believe this mantra also, children stop questioning. They assume it’s their fault, and they internalise the message that it’s them, their problem, and that they are the ones who are bad.

“I didn’t want to say it at first. I didn’t want to see it like this, in this way,” Rougely says of the possibility of a prejudiced motive being behind her daughter’s burn marks. But a scar around the neck must be much harder to ignore than off-hand comments. Rougely has since asked the school for compensation, but, as The Dallas Morning News reports, “the school contends the girl’s lawyer is using race to take advantage of an accident for financial gain”.

We have to keep faith in our school systems, otherwise nobody would ever leave their children at the gates. But it’s important to also be realistic. Teachers are not exempt from being judgemental and prejudice, nor are school’s better equipped at dealing with structures of racism than any other public place of work. Yet while those in work may be equipped with the knowledge and the language to distinguish micro-aggressions and tackle them, most children do not. For the rest of us, the least we can do is give them the benefit of the doubt.