Rebecca Hall is uncovering the hidden history of women-led slave revolts – and she’s doing it via graphic novel

Historian Rebecca Hall speaks to Leyla Reynolds about hidden histories, women-led slave revolts and why she's doing academia differently.

Leyla Reynolds

07 Jun 2021

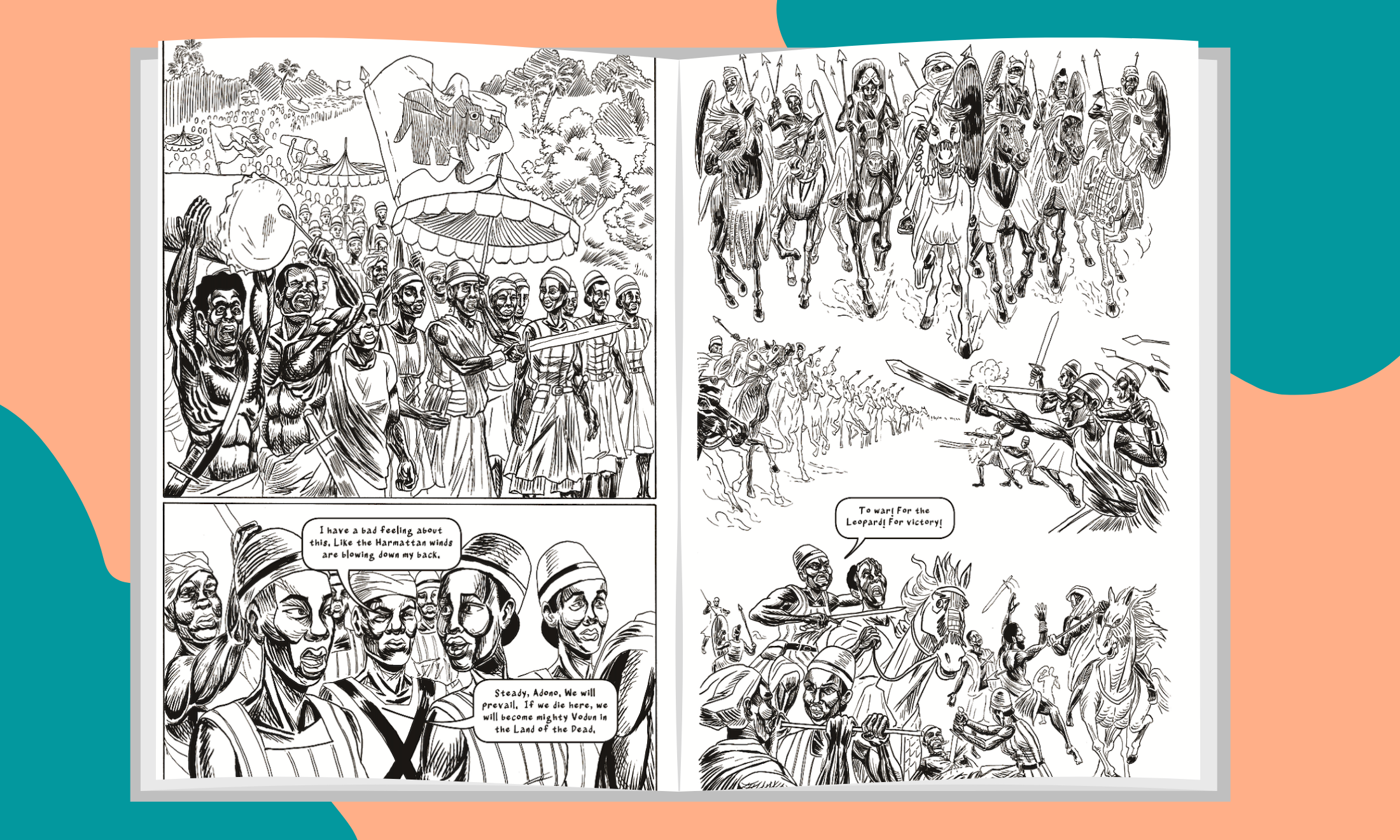

Rebecca Hall/Hugo Martinez

You don’t often see historians presenting their work via illustration. But thinking about it, why not? What better way to bring the past to vivid life?

That’s exactly the approach taken by Dr Rebecca Hall, a historian who’s seeking to uncover the hidden legacies of transatlantic slavery via graphic novel. Her new book, WAKE, is a collaboration with artist Hugo Martinez and explores the under-researched history of women-led slave revolts in the Americas. The book explores both the revolts that took place on slave ships during the so-called ‘Middle Passage’ stage of the Triangular Trade and uprisings that happened in colonial New York, pieced together from historical evidence ranging from slave ship logs to forensic matter taken from enslaved African burial grounds in the city.

Dr Hall – who has descended from Black enslaved Africans herself – spoke to gal-dem about the project, histories that shouldn’t be hidden and how slavery has shaped our modern conceptions of self.

gal-dem: What do you want the impact of this book to be?

Dr Rebecca Hall: I hope that it gets adopted, and is used in teaching, in high school and on the curriculum. I’ve taught everything from law school, to graduate school to college and I’ve seen all of the horrible ways the history of slavery and race is taught. This should be an intervention into that. I want African American people to take pride in their ancestry and to see their ancestry is a form of power. I want these women’s stories to be told and I don’t want to see such violent erasure.

It’s unusual to publish a piece of historical research like WAKE as a graphic novel – what led to the decision?

I chose the graphic novel format because I figured this was a passion project, and that I was gonna self publish it. I love graphic novels, and find them very powerful – particularly those that deal with important topics. I’m not an artist at all; I can’t draw sticks and my past writing experience has been steeped in academia. So writing a script for a graphic novel was a complete new direction for me, a really steep learning curve.

How did you feel the relationship with the artist influenced the progression of the book?

We worked together every step of the way. [I ended up signing] a contract with Simon and Schuster [after an extensive bidding war], and once I realised what a big project I had just taken on, we hired a team of comics book writers as a kind of pre-production team. They helped write with me visually or I would tell them what I wanted to try to get across and they’d come up with suggestions like storyboarding. As the writing proceeded, I became more and more confident in being able to describe what I wanted to see on the page.

What’s one of the most surprising journeys you went on whilst researching the book?

One of the things that really struck me was how the court records for the 1712 revolt (wherein in New York City four enslaved women were tried for a revolt in which 27 white people were killed) are kept in the New York Municipal Archives. This building, that has every closed court case for the city of New York, from 1680 to the present, was disorganised and falling apart. The [records] were not being cared for. When I went back we bought a digital camera and photographed everything so at least we had it.

Another significant passage in your book says that the higher the number of women on a slave ship, the higher the likelihood of a revolt. Could expand on why that was?

One of the things that the internet allowed historians to do is consolidate their research. These slave trade historians created something called the Atlantic-slave trade database which you can access online [which shower higher incidences of slave ship revolts than expected]. That surprised everybody because everyone thought slave ship revolts were very rare because it was basically a form of suicide.

They looked at the ships that had revolts, and compared them to the ships that didn’t have revolts to try to find if there was a difference. And what they found was that the more women on the ship, the more likely a revolt, and then they dismissed their own findings!

I then spent time researching everything, like the British trade, which was a very highly regulated business enterprise. There were procedures about how a slave ship was to be run. What I discovered was that once the ship left the shore of West Africa, women would be unchained and brought aboard loose on deck. I think that the assumption they were operating under was that women weren’t dangerous.

Would you say there was a difference in the approach of male and women-lead rebellions?

I think the term ‘rebellion’ is something that people do in the face of valid authority and sort of seen outside the realm of the political. I prefer to use the term revolt. I don’t think that the revolts on ships were different depending on the gender of the people instigating it, or it’s just that there were more revolts on ships that had more women and, and the historical bias of the past was that historians today couldn’t understand why that was possible.

There seemed a synergy between the discrimination that you wanted to speak about historically and also that that you experienced even in trying to trying to excavate these historical stories. I wondered if there was a particular methodology in combining the modern and historic and wondered why you thought that was important to do so in WAKE?

The story that I wanted to tell is really a trans-temporal story. I came into it trying to understand the legacy of slavery, and how it shaped race and gender. And so that’s what makes the graphic novel medium so effective because it allows this sort of temporal play. You’ve got text which is linear in one direction and then you’ve got art, the visual image, which is a kind of all at once experienced.

And there’s something about the relationship between those going back and forth that allows you to combine living in the afterlife of slavery and living in the wake of slavery. And my positionality, being a direct descendant of enslaved people, of having my paternal grandparents actually be slaves, I think was an important part of the story. I wasn’t just interested in telling a story about stuff that happened in the 1700s.

One of the quotes of yours that I really appreciated was ‘as part of living in the wake of slavery, we must defend the dead and fight the violence inflicted on them in their erasue from the record’. Was this one of your main motivations to write the book?

I think as a historian it requires real historical rigour when you’re doing this kind of research. So, I was involved in a lot of protests. And well, the history of racism and how, like you said, it continues to morph and it’s depressing. The resilience and the ways in which enslaved people fought back.

It seems like direct action really can make a difference!

There’s this thing called historiography, which is a methodology that historians use. The first histories of slavery that were written in the US were written by Southern white male historians, who wrote these stories about how slavery in the US was this benign, and important civilising institution and that’s why apparently there weren’t any slave revolts in the US.

And then as time went on, people disagreed. And later as feminist historians started writing history, they were like, ‘Okay, well, if women weren’t involved in slavery, well, let’s look at the kind of other kinds of resistance that enslaved women did’, which was very powerful.

WAKE by Dr Rebecca Hall is available to buy now

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?