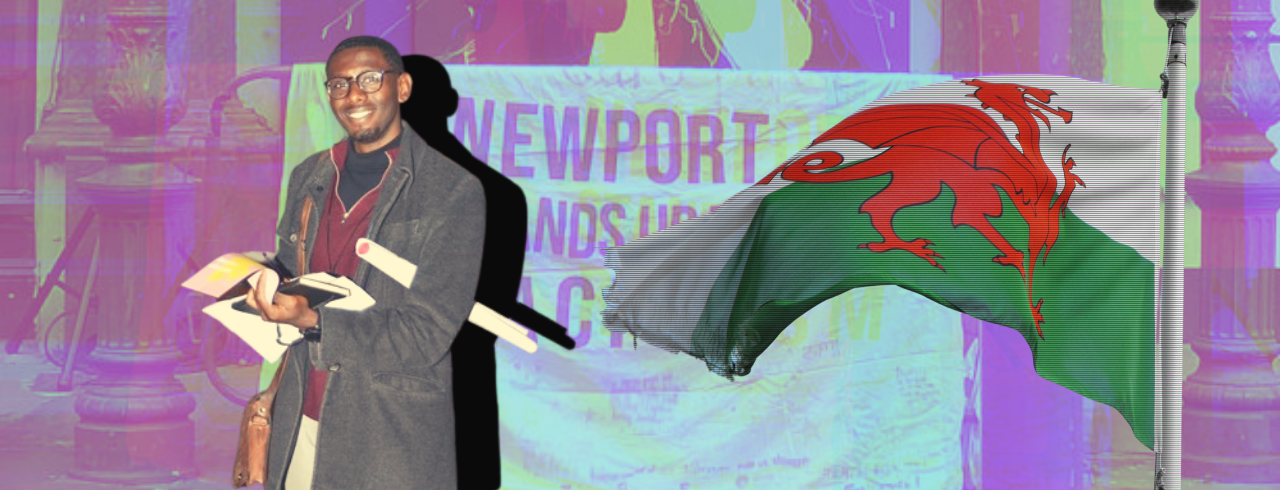

image by Hannah Buckman

I was 15 years old when I was spied on by the British state.

It’s been well documented that undercover police officers have stolen dead children’s names, had secret families, and spied on activists. I was one of those activists. I met Marco Jacobs in 2007 at No Borders meetings in a time when Cardiff was experiencing a renaissance of political activism as the war in Iraq mobilised the country.

No Borders is a loose network of groups worldwide working to resist and dismantle borders and immigration controls. Marco was funny, charismatic, and outgoing. He was around 5”9, white with a broad northern accent. Marco said that he worked driving trucks, which explained the long periods of time away from Cardiff. He liked heavy metal, cracking jokes and drinking lager. He built our relationship knowingly and slowly with a charismatic personality and a wicked sense of humour. It’s easy to bond with people on things like demonstrations, as we frequently had visible pickets outside the UK Border Agency (now UK Visas and Immigration) in Cardiff, protesting the racist border regime.

Then, he would show up to the same punk gigs I was at, and give us all lifts home afterwards. I always felt extremely safe with him. I had his mobile phone number and he was one of my friends on Myspace. On one occasion, I had acute anxiety at a punk gig where I received repeated unwanted advances from a man nearly 10 years older me, and Marco stepped in and stayed at my side throughout the night. He knew where I lived and what school I went to. I was especially comforted by our conversations where he offered me emotional support when a mutual friend was deported. I was devastated. Now, I wonder if that was genuine concern or part of a wider plan to get me to lower my defences around him.

The Guardian confirmed that Marco Jacobs was an undercover officer sent to infiltrate radical activist spaces, soon after Mark Kennedy – an undercover London Metropolitan police officer who infiltrated activist groups – was outed by climate change activists in 2011. We began to suspect Marco might also be an undercover police officer, and one friend once asked him straight. He deferred the question with nervous laughter. Within a few months, Marco had left to be a gardener in Cyprus and we never heard from him again.

The Guardian told us the news first, then released the national story the next day. It was surreal to see Marco’s face all over the news. A sense of hysteria overcame activist groups in the country – one that hasn’t quite left. I remember having my dinner on my knees as Marco’s photo was plastered over the evening news, and double checking to see that he hadn’t deleted his Myspace. I wasn’t yet in sixth form.

Undercover policing is about deviance, how close you are to it, how far you are from it, and how the state can use that to menace you. Not many, if any, of the friendships from those activist groups survived. There was betrayal, lies, and Marco even tricked women into having sexual relationships with him. He was successful in that he deeply devastated relationships and friendships beyond recognition. He pushed people away from each other and drove wedges on purpose, and ruined the mental health of many people. Lots of people who knew him don’t undertake political activism any more.

This tactic of betrayal, lies and infiltration has been employed since the Counter Intelligence Programme (COINTELPRO) in the 1950s-70s. COINTELPRO was a series of undercover projects run by the Federal Bureau of Investigation aimed at disrupting, infiltrating and dismantling domestic political organisations in the USA. It targeted everyone from the Black Panthers to anti-war activists and they employed a diversity of tactics; psychological warfare, physical intimidation and harassment. It sounds painfully familiar.

I’ve often wondered how much inspiration the British state has gained from COINTELPRO. Undercover police officers have targeted climate change groups and anti-racist campaigners – Doreen and Neville Lawrence were targeted by the Metropolitan Police while campaigning for justice for their son, Stephen, killed by a racist street gang. We know the FBI put crack cocaine in communities to weaken the black power movement. I’ve often wondered deeply about the links between our wars in poppy-producing countries and the flooding of heroin into British streets in black and minority ethnic communities.

Growing up a working-class person, we don’t talk about state violence. We bury our heads in the sand. Our communities are continuously traumatised by the wounds of colonialism that have divided and conquered racialised bodies and actively encouraged communities and individuals to turn on each other. This is exactly what Prevent promotes us doing, turning on our own communities. When someone goes to prison and when the police do dawn raids in racialised areas of south Cardiff, it’s a secret. We hurry by, try hard not to stare and bite our tongues to keep our eyes nailed to the grey pavement, matching the council estates around us and the skies above us.

Knowing Marco is one of the biggest open secrets I have ever kept. His name is silently communicated in knowing glares between people who knew him on the rare occasions we bump into each other. “Yasmin,” my friend told me, “My parents escaped Chile when I was a kid. You have no idea what they had to do to get us out of the country. We were spied on as kids by the Chilean government in Manchester growing up. I thought I’d know if they came for me again, I’d know if I had been spied on again”. Then he burst into tears.

Politically radical people of colour are an absolute double whammy for the British state. In a post 9/11 world we’re both hyper-visible and minorities. We’re hyper-visible to state controlled surveillance like Prevent, and minorities when nobody cares that we have been spied on. I was a teenager when I was spied on by the British state. For others, this was another example of lifelong state surveillance. Undercover surveillance is the continuation of the colonial gaze and we need to take notice.