Belle Maluf/Unsplash

India’s new ‘Marriage Bill’ is supposed to empower women and girls. Instead, it will roll back their rights

A new proposal making its way through the Indian parliament is not as progressive as it appears.

Simar Deol

24 Dec 2021

Right-wing populist leader and Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, made a stark declaration that it was time for female empowerment on the 74th Indian Independence Day in August last year. “Our experience says that whenever there is an opportunity for women power in India, they have brought laurels to the country, strengthened the country,” he said.

In a country that faces a myriad of gender-based violence and socio-economic inequities, concrete policy changes prioritising women’s rights mark a welcome change. Yet the primary solution Modi’s government offered, however, was to consider changing the legal minimum age for women to get married from 18 to 21 – matching the pre-existing laws for men. A task-force created shortly after Modi’s speech by the Ministry for Women and Child Development submitted a report recommending similar changes. These changes were debated in the winter parliament session on 23 December, as part of a bill amending the Prohibition of Child Marriage Act of 2006. The proposal has been recommended for further consideration to the parliamentary standing committee before it can be put to vote next year.

The primary aim behind the task force’s recommendations is to increase the quality of lives of women and young girls by offering them the opportunity to focus on educational, professional and vocational training by removing the pressure of early marriage. “When it comes to marriage, you put a girl at a disadvantage in accessing opportunities because the law is already embedding a message [to her] that after 18, [she] has another job to do,” Jaya Jaitly, who steered this task force, tells the Wire. However, the task force has not made their research, including how many stakeholders they interviewed and from what regions, nor their report, available to the public.

“While on the surface, there appear to be noble motivations behind the proposal, in reality, the outcome will be vastly different”

While on the surface, there appear to be noble motivations behind the proposal, in reality, the outcome will be vastly different. Research conducted across the country by Delhi-based NGO Partners for Law in Development (PLD) has found that the current PCMA is primarily used by parents to oppose self-arranged and eloping marriages in consenting adults. 65% of the 83 verdicts analysed had been filed under PCMA by parents in order to prosecute the husband or seek custody of their daughter. PLD also found that eloping couples use this act when they are seeking protection, cohabitation, bail or when attempting to defend themselves of criminal charges – usually filed by family and relatives in the hopes of annulling a marriage against their choice.

The National Coalition Advocating for Adolescent Concerns (NCAAC) has raised other important issues – primarily young women and girls’ access to sexual and reproductive healthcare, as well as social security benefits reserved for maternal schemes. Healthcare systems, as they are currently structured, primarily benefit married women. Unmarried women in consenting relationships often face judgement for engaging in premarital sex and can be denied basic sexual and reproductive care as a result. Increasing the legal marriage age will most likely not alter women engaging in sexual activity, but it will deter their chances of receiving adequate medical support. Changing the legal marriageable age is simply masking the realities of child marriage, as it fails to address the socio-cultural and structural roots underpinning the widespread problem.

“Changing the legal marriageable age is simply masking the realities of child marriage, as it fails to address the socio-cultural and structural roots underpinning the widespread problem”

These legal changes will also further increase parental and familial coercive control. Currently 67% of all cases filed under this act are logged by the girl’s parents or family. This bill will also result in increased criminalisation against young men and women in consensual, non-coercive relationships as it can be used as a punitive tool to deny adolescent sexuality. During Modi’s tenure, there has been an increased crack-down on modern relationships, including romance, dating, premarital sexual activity, specifically targeting sexually liberated women.

Currently, the proposal has been cleared by the union cabinet and was introduced and debated in a parliamentary session on 22 December. It is under review by the parliamentary standing committee for further consideration before it goes to vote. However, activists, NGOs and women’s rights movements including Action India, SAMA Resource Group on Women and Health, Vishaka are becoming increasingly vocal in opposition to this bill. These groups have partnered with NCAAC and submitted a proposal to the government urging it to re-evaluate the conditions of the legislation. The proposal encourages the parliamentary committee to conduct further stakeholder interviews with more respondents, including civil society organisations working on issues relating to early marriage.

Activist groups are also recommending greater investment into educational access and education quality, with support for women and girls including hygienic bathrooms with sanitary products – a well-documented deterrent for girls to attend schools. Access to high quality education and thereafter professional vocational training can help young women attain financial freedom, unshackling their dependence on marriage and families. This surely would allow for the empowerment this bill hopes to achieve, they argue.

“This pseudo-feminist empowerment narrative being adopted by Modi and his task force poses a real threat to the wellbeing of women and girls”

This pseudo-feminist empowerment narrative being adopted by Modi and his task force poses a real threat to the wellbeing of women and girls. Naturally, there is a need to review the barriers faced by Indian women in accessing educational and professional opportunities. But these needs must be contextualised within the realities of existing cultural constraints in Indian society.

The empowerment of women within the country cannot be achieved through isolated legislation, but through policy-making that adopts a rigorous analysis of interdisciplinary structural factors preventing women from achieving gender equality. It’s easy for governments, organisations and individuals to co-opt terms of empowerment and liberation, especially as demand for real change continues to strengthen across communities in India. But cosmetic legislation providing positive talking points, such as changing the legal marriageable age, may have long-lasting, distressing consequences – especially for the very women and girls it is supposed to benefit.

The Gulabi Gang is a sisterhood fighting against domestic violence in India

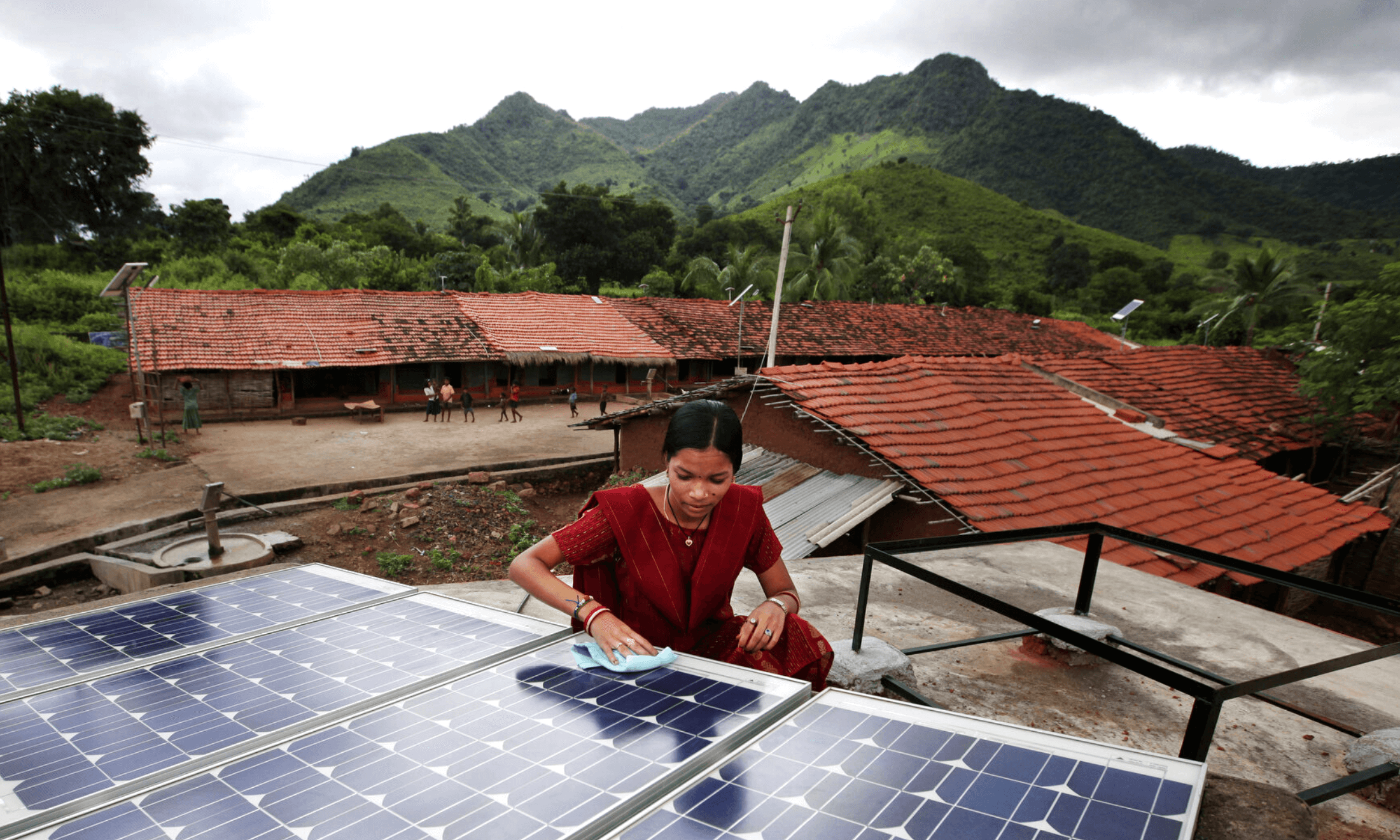

After a gruelling year of heatwaves and floods, Indian climate groups get to work

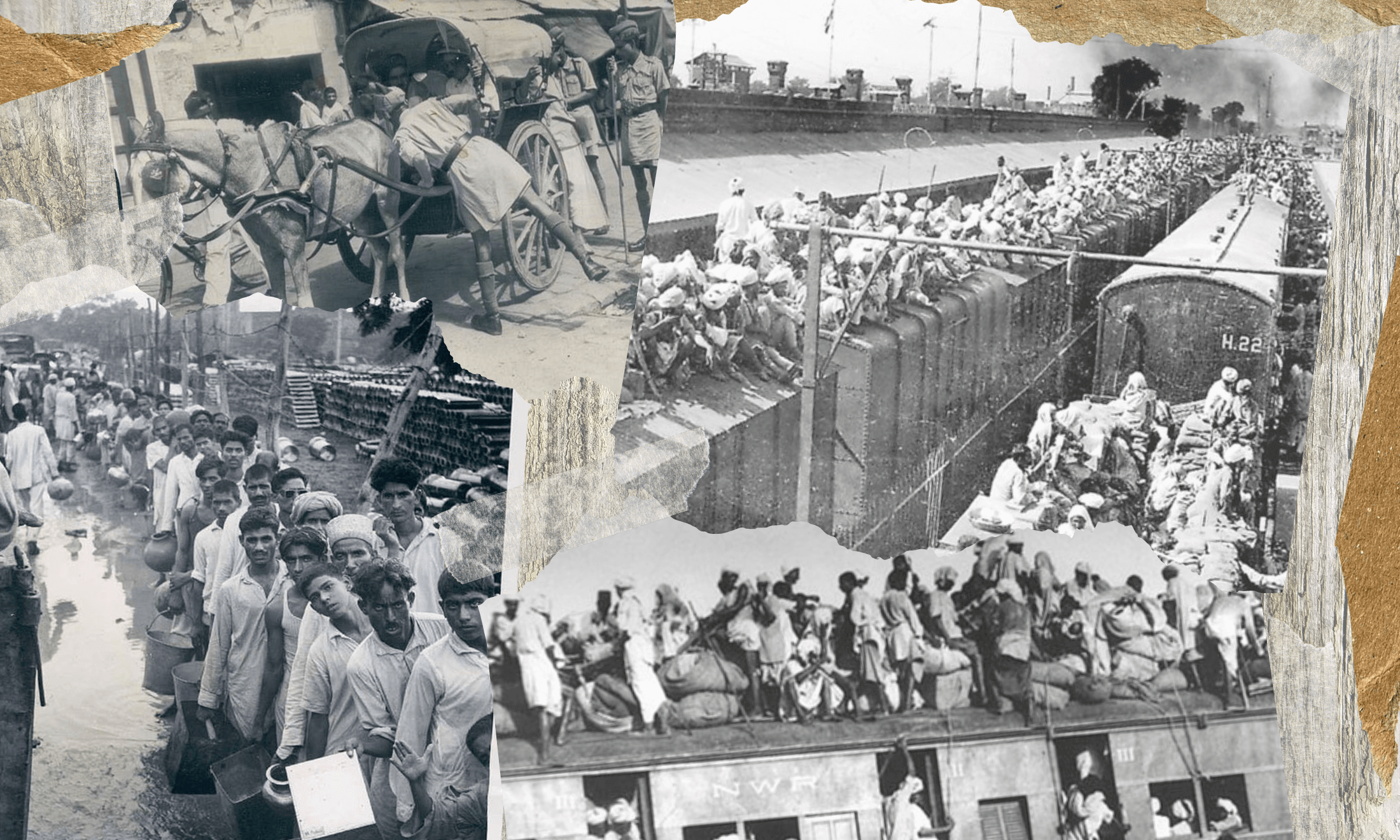

‘The other side’: Remembering Partition 75 years on