How interior design brings comfort to the depths of my chronic illness

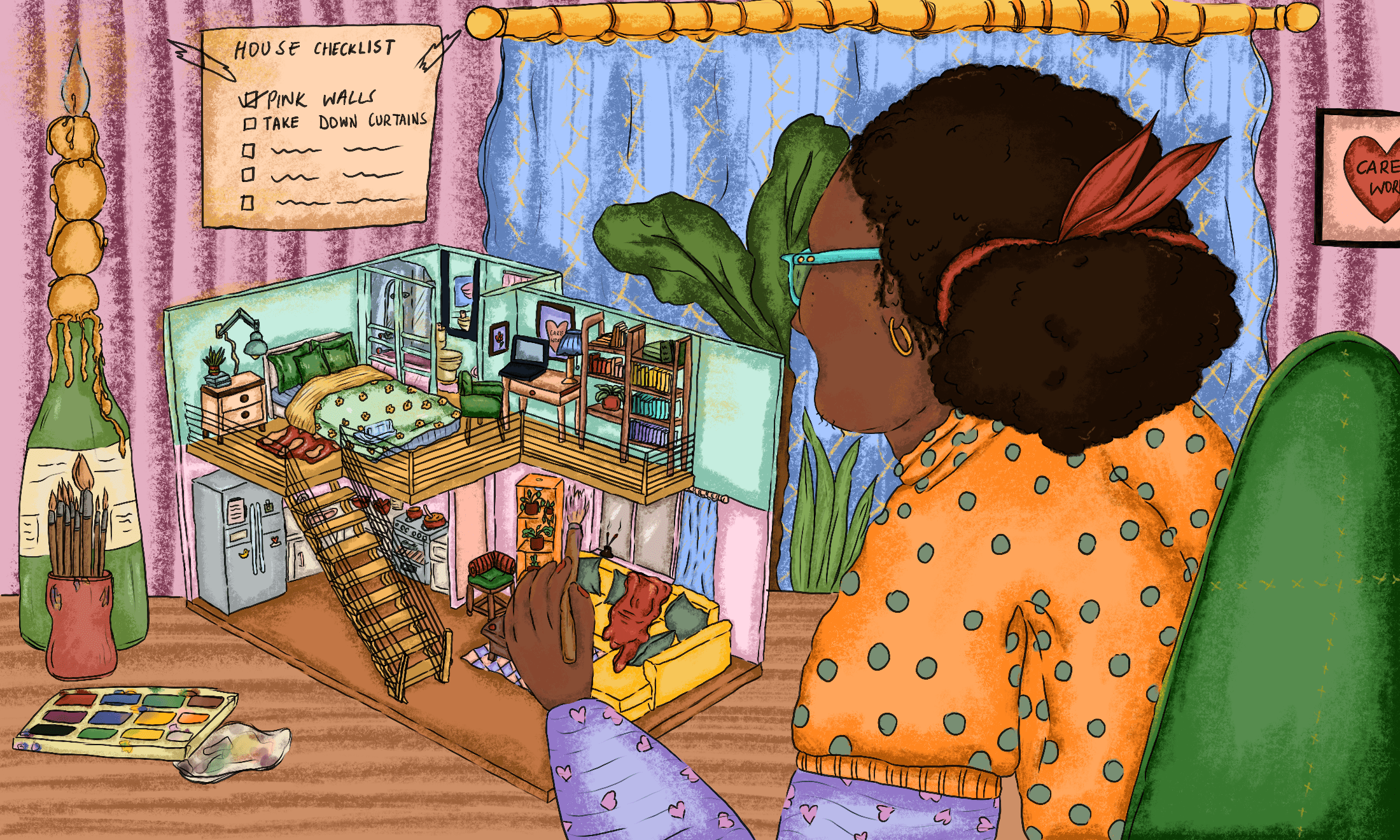

When I was diagnosed with fibromyalgia as a teenager my artistic dreams changed. But interior design has become a new outlet for my creativity.

Dorneka Ward

25 Nov 2022

Parishma Patani

If you asked 12-year-old me to describe what her teenage years held for her, she would have presented an exciting story. There would have been no shortage of dance classes, fantasy books that she couldn’t put down, crushes that turned her cheeks red and arguments with friends over their theories of the American pre-teen shows that dominated their lives.

I am certain that she would not have mentioned oncoming devastating pain. Pain that crept so quickly and unsuspectingly into her life, that within the course of months, her hope for her future had crumbled away and she could no longer dress, wash or walk without any assistance.

Unfortunately, this is exactly what happened when in 2016, my life came to a complete halt.

Over the course of the summer, I began experiencing widespread bodily pains that both my family and I thought were simply due to the arrival of puberty. But it wasn’t long before the intensity of these pains increased, becoming so bad that my school attendance levels, general physical health and mental health declined. Eventually, I began the journey of obtaining a medical diagnosis to figure out what exactly was going on with my body. Aged 13, I underwent a series of appointments, consultations, tests and general assessments. No diagnosis seemed to fit, until my consultant realised that my condition matched the description of fibromyalgia.

“I struggled to derive any sense of joy and pleasure from my own creative expression or the activities that had previously sustained my personal vibrancy”

Fibromyalgia is a chronic health condition that causes symptoms such as widespread pain, fatigue and migraines. Each of the symptoms, and the strength they manifest with, is different for every person. For me, it was severe enough that I had to leave high school.

Not only was I unable to participate in my beloved hobbies or function as the rest of my family, friends and peers continued to, but my entire relationship to life had changed.

In addition to my pain symptoms, I had also gained a sensitivity to bright lights, loud music and the general hustle and bustle of the outside world. Now, I struggled to derive any sense of joy and pleasure from my own creative expression or the activities that had previously sustained my personal vibrancy. One of these was my city’s Carnival. It used to be an event that I welcomed at the end of each August, a festival to celebrate the freedom of my Caribbean ancestors and my pride in our lineage as transformational and courageous people. However, with my illness, the display of colour and ceremonial rhythm of soca music induced vicious migraines and nausea. I lost my excitement for seeing the feathered costumes and unbridled jubilance of my community, instead seeing it as evidence that I was incapable of participating in enjoyment.

“Engaging with hard plastic chairs, thin pavements, high shelves and clinically bright lights all had a significant negative impact on my symptoms”

Slowly, a fear of existing as myself amongst non-disabled people emerged. I felt as though I couldn’t live life or maintain my relationships without the shadow of invisibility, bodily pain and being seen as incapable. I was concerned that my illness was distorting other people’s perception of me. This fear was also exacerbated by the fact that the design of my local environment was not tailored to the needs of disabled and chronically ill people. Engaging with hard plastic chairs, thin pavements, high shelves and clinically bright lights all had a significant negative impact on my symptoms and my ability to be comfortable. Because of this, I had to navigate my daily life slowly and cautiously, which often inspired aggravation in others – especially in a long queue for a service.

So, I retreated indoors. I stopped seeing friends, doing my favourite things and instead stayed at home. At first, I found it refreshing to have my own company. But with time, I began to feel isolated and disconnected from the version of me that enjoyed creativity. On my worst days, I couldn’t lift my head, never mind dance or pick up a pencil to write about the stories I dreamed of. All I did was remain in my bedroom, occasionally reconfiguring the position of my furniture and furnishings.

“The more I added, designed and used my creativity to formulate my space, the more my hope for life returned to me”

Ever so slightly, the possibilities of expression through interior design opened up to me, little by little. Making myself more cosy in my space allowed me to implement self-care and creativity into my choices of material, texture, lighting and colour. Although I could not control my body and what it could do, I could dictate how I wanted to feel and be supported. No one could decide this but me. No one could tell me how to find healing in my own room, but me.

I decided to design a place that supported my needs, as proficiently as I could. With the help of my mum, I renewed my previously drab surroundings into an oasis that represented the essence of healing. White bedroom walls became pink – a gentle hue that symbolised the love and care that I promised to treat myself with. Curtains were taken down and black-out blinds wrapped with pearl twinkle lights went up, so I could control how much light came into the room in the event of a bad flare-up of symptoms. Soft blankets, pillows and plush toys decorated the surface of my bed, fulfilling my physical need for comfort.

This new found sense of autonomy reaffirmed my belief in myself and my imagination, despite what I was going through. I could be capable. I could be vulnerable, and able to be in pain, without shaming myself for it. The more I added, designed and used my creativity to formulate my space, the more my hope for life returned to me. I still struggle with being outside my home at times. But my room, this space of comfort and autonomy, has provided me with the restoration and empowerment I need to move forward with hope, passion and the belief that I can achieve all I desire.

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.

‘As disabled people we have been living in a cost of living crisis for years’

Meet Onyx, the zine-making collective magnifying the voices of disabled people of colour

Productivity culture at Oxford uni, my chronic illness and me