Charity Atukunda

A new sickle cell treatment fills me with a long-forgotten feeling: hope

It's taken two decades for a new treatment for sickle cell disease to become available in England. One 'Sickler' reflects on the news.

Tanya Akrofi and Editors

25 Nov 2021

“Hope” is the thing with feathers

That perches in the soul

And sings the tune without the words

And never stops – at all

– Emily Dickinson

On the morning of 5 October, the news from my bedside radio announced a new treatment for Sickle Cell disease. I sat upright in bed, threw off the covers and shouted downstairs. It was already online and on television. My sisters rang excitedly. Friends messaged.

I remember thinking that there is something fragile about hope, something intentionally abstract. It refuses solidity, preferring to flitter and float, slippery like soap. That morning I held tightly onto it, afraid that it might fly away.

I was diagnosed with Sickle Cell Anemia when my parents were still living in Ghana. It’s my first memory: crawling, unable to stand and the tight feeling in my legs like they were being firmly gripped. I remember that pain.

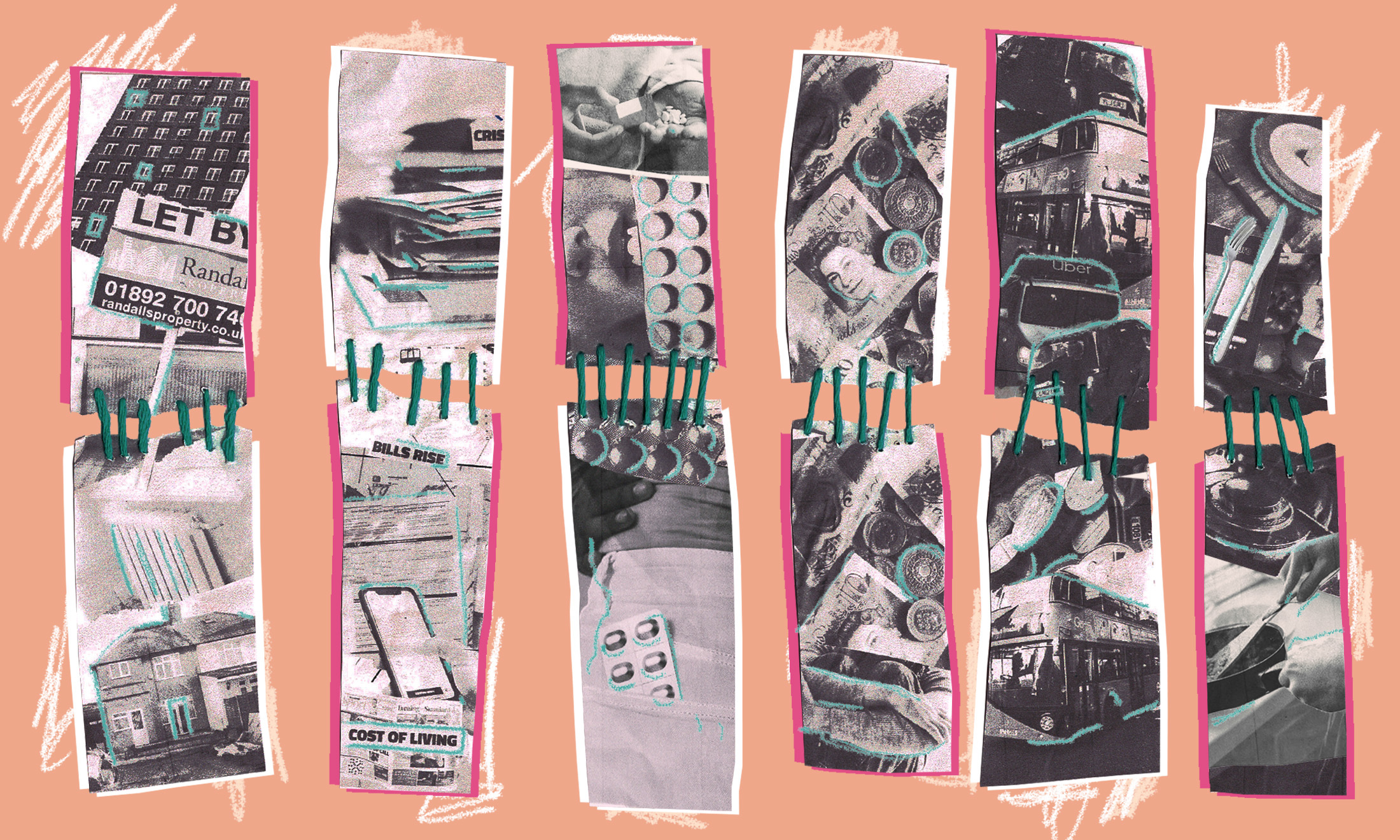

When my parents moved to London in the late ’80s, the landscape of our lives changed completely. Sickle Cell wasn’t well understood in the UK then and my dad carried photocopies of doctor’s letters and past admission notes in a folder which we took with us whenever I had a crisis and had to go to A&E. A crisis is a flare-up, it’s excruciating pain, shortness of breath. It can be frightening.

“The persistent pain and the almost constant isolation were more than I was mentally equipped to deal with”

We never knew if we’d meet familiar nurses and even with our trusty file, it would take hours – hours of sitting and crying in the uncomfortable plastic chairs under the glaring fluorescent lights and noises of Casualty. I hated it. Whenever I felt a crisis approaching, I hid the symptoms for as long as I could. Anything to avoid those chairs, those lights.

It wasn’t just A&E I hated, being admitted meant the sterile environment of a hospital ward, being away from any sense of normality. While on admission to the children’s ward aged 14, I was diagnosed with depression. The persistent pain and the almost constant isolation were more than I was mentally equipped to deal with. I felt like I might always be broken, never whole. Never normal.

I turned 18 and desperately wanted another life. I learned more about complementary therapies – non-medical treatments which exist safely alongside conventional medicine, and I was lucky that my GP practised acupuncture. My mum introduced me to massages, not just for relaxation, but as a way to relieve the pain, grief and anxiety which haunts the body; all the unwanted baggage which comes with a chronic disease. I stopped praying for a cure and accepted my condition, designing my own ways of living with it.

“After years in what felt like medical purgatory, neither moving forward nor backwards, there was finally movement”

Little rituals helped: warm baths in the morning to ease aching joints, rest structured into all my activities, and warm oil rubbed into my knees before bedtime. And I stopped going to doctors’ appointments. DO NOT DO THIS! It wasn’t sensible or advisable, but I was desperate to regain control over my life. I still go to the physiotherapist, I see my GP for pain relief and I walk with sticks and use a wheelchair on difficult days. But I felt misunderstood by the NHS, like so many people with chronic illnesses. It felt easier to find my own way through the labyrinth of it all.

Then Covid-19 came and I immediately began shielding. Suddenly I was an island, avoiding all public interactions – the recipe for a raging resurgence of depression. If hope truly was a tiny bird, then its song was now so faint as to be almost inaudible. So quiet that I was almost sure it had flown.

So on that morning when the treatment was announced, it felt as though it was back. Everyone could hear it too. I ate breakfast feeling lighter than I had in so long. After years in what felt like medical purgatory, neither moving forward nor backwards, there was finally movement. Finally some light.

“Hope is such a fleeting commodity for those of us who suffer from chronic conditions”

The treatment (called Crizanlizumab) is administered by an IV drip and works by preventing the restriction of blood and oxygen which leads to a crisis. I don’t know if it will work for me, but I feel better just knowing that the medical world is still paying attention to us Sicklers. Those of us who have had to find our own ways of coping and dealing with this illness. Those of us trying our best to fashion liveable lives in the midst of debilitating pain. The bird sings for all of us.

After years of avoiding it, I’ve made an appointment with a haematologist, re-registering in the hope that I can learn more about the new treatment, hoping it makes a difference to the way I live my life.

Hope is such a fleeting commodity for those of us who suffer from chronic conditions. Fleeting, fragile but so so precious.