Omar A via Flickr

Is the climate emergency making Hajj even more exclusive?

As Saudi Arabia swelters, pilgrims pay top dollar for comfort. But what will happen as the heat gets even more unbearable?

Zainab Mahmood

05 Oct 2022

“Part of the Hajj psyche is that if I struggle now, it just doesn’t matter. Because [in] the big scheme of things, this is nothing,” says Nazlee Haq, a family friend of mine. I spoke to Nazlee Chachi (aunty in Urdu) over Zoom to find out how she coped with Saudi Arabia’s extreme heat during Hajj in August 2018. “Even if you are coping badly, you just take that as a sign; this is one of the hardships that you have to go through,” she adds.

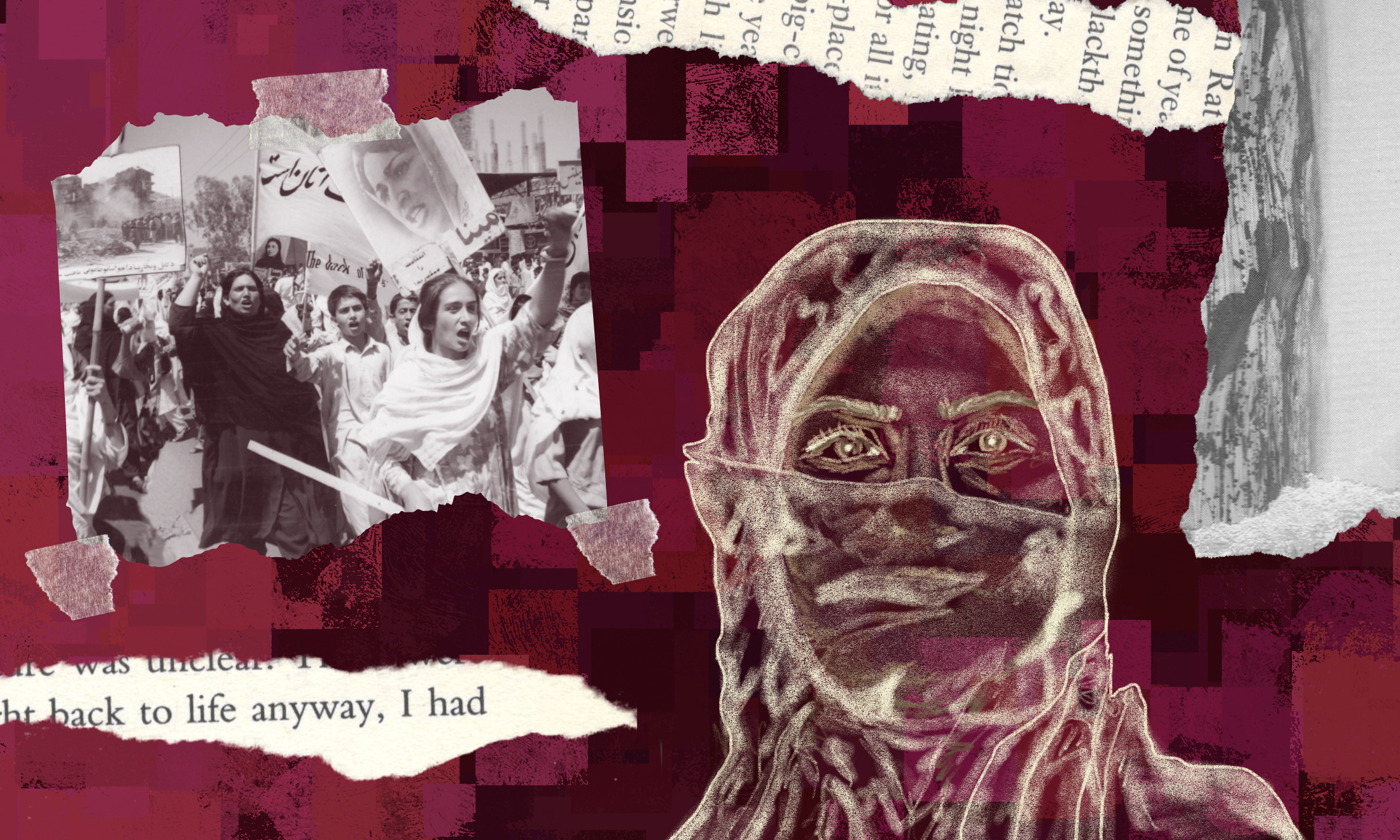

For the past few years, as global temperatures rise due to the climate emergency, Muslims continue to perform Hajj – the holy pilgrimage for adherents of Islam, who make up almost a quarter of the world’s population. Women pilgrims are fully covered in dark, synthetic fibres as they walk for hours in the same temperatures that caused school closures in the UK this summer. Nazlee Chachi recalls temperatures of just over 40C during the day and Seema (another aunty from my local Pakistani Muslim community), who performed the rites in July this year, describes the nighttime temperature of 38C as “pleasant”.

“Between 1989 and 2019, the temperature in Mecca rose by almost 2C, which is well over the global average”

If UK heatwaves this year haven’t yet triggered anxiety around global heating and the climate crisis, the sheer temperatures in the Gulf region and lack of preparedness for rainfall might do it. Between 1989 and 2019, the temperature in Mecca rose by almost 2C, which is well over the global average, and yet 2 million Muslims continue to be led to Hajj by their faith every year.

Neeshad Shafi, a Qatar-based climate advocate and environmental activist, says that extreme heat can cause severe dehydration and also push dust particles into the air, worsening the effects of any existing allergies or respiratory issues. “My mother has breathing issues, and the [combination of the] dust and [her] allergies is quite phenomenal,” he explains. “The more it’s heating up, the more dust comes out.”

So as the temperatures get hotter and the local climate changes, multiple problems begin to present themselves. How will the pilgrimage continue without any urgent intervention? And will adaptation measures be accessible to everyone?

Short-term adaptation that’s bad for the planet

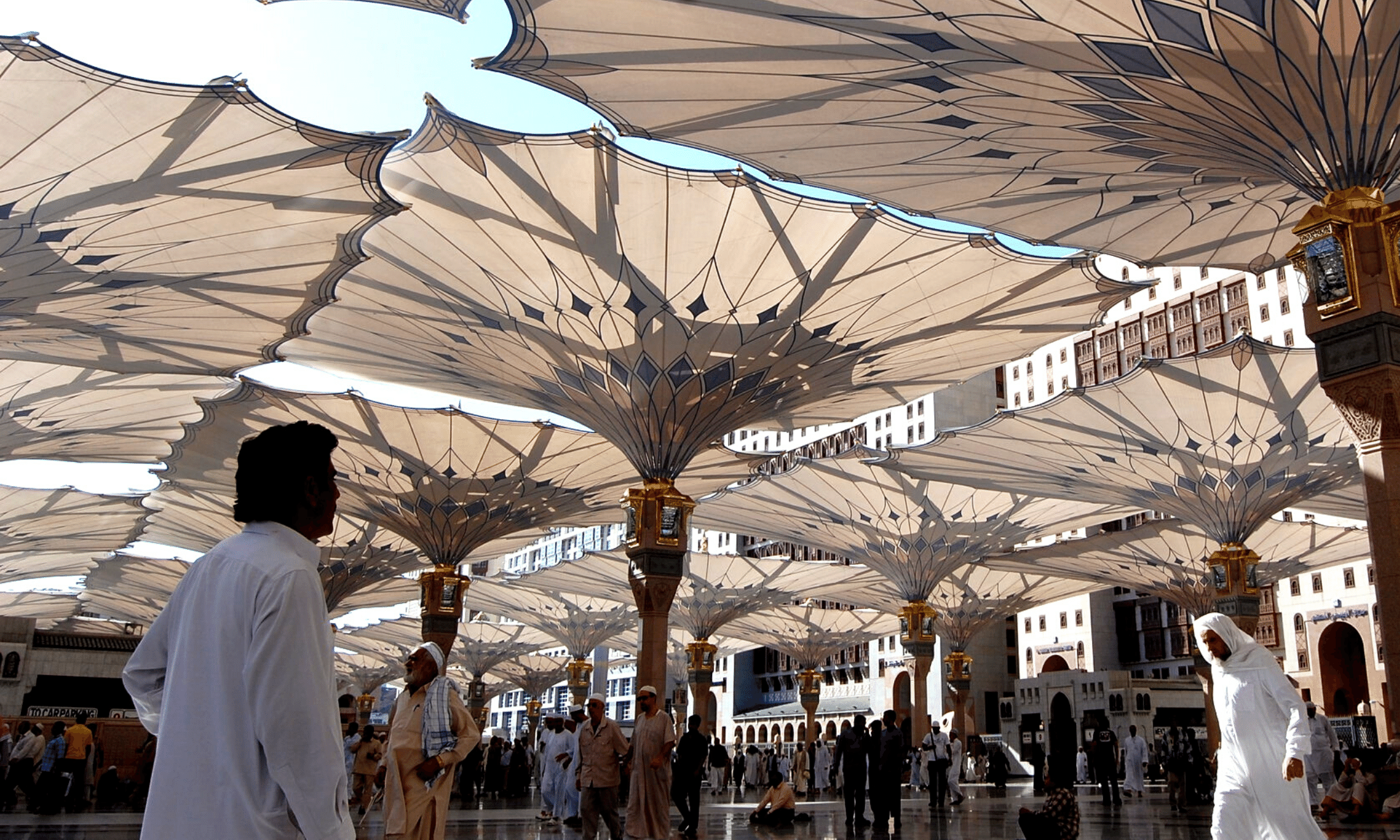

Neeshad and Nazlee Chachi pointed out that the two prominent mosques in Mecca and Medina are fully air-conditioned and that there are systems spraying water into the air to lessen the impact of heat stress. Seema Aunty also described umbrellas providing shade outside the Prophet’s mosque in Medina, Saudi Arabia, as “something out of a sci-fi movie, with the same kind of artwork as the mosque: green and gold.” This infrastructure may be helpful in the short-term, but with Neeshad citing that temperatures in the Gulf region are rising “two times faster than Europe”, he envisions the future of Hajj as essentially an indoor activity, fully-covered with air conditioning, “like an alien movie.”

Neeshad mentions the possibility of introducing more vehicles to reduce the amount of walking in the rites, which consist of walking seven times around the Kaaba, Islam’s sacred shrine situated in the Great Mosque, and between the hills Safa and Marwa, amongst other rituals. These technology-based strategies would make Hajj even less affordable to the most disadvantaged and more carbon-intensive, unless Saudi Arabia adopts the use of renewable and solar energy.

“In the case of the Great Mosque in Mecca, solarisation would save over 1m litres of gasoline, but concrete plans to implement this remain to be seen”

Ummah for Earth, an alliance of several organisations working to empower Muslims to lead the way to climate justice, and Greenpeace Middle East published research last year analysing the potential costs and impacts of solarising ten mosques worldwide. In the case of the Great Mosque in Mecca, solarisation would save over 1m litres of gasoline, but concrete plans to implement this remain to be seen.

Saudi Arabia might be ready to invest in more cooling infrastructure to comfort pilgrims and continue running its lucrative business, but preparing for the possibility of flooding is another ball game. “It may also rain, and suddenly a flash flood in Mecca may take people’s lives away,” suggests Neeshad. He says that flooding hasn’t been as disastrous in Mecca as in the UAE in the past as it’s an open space, but the reality of the climate crisis currently means preparing for all extremes.

A growing privilege

Nazlee Chachi, Seema Aunty and so many others have meaningful Hajj experiences that transform them spiritually, despite the physical challenges and high temperatures; but this is a privilege for fit, non-disabled Muslims and comes at a high price. Nazlee Chachi spent £10,000 on her Hajj tour package.

The commercialisation of Hajj to the extent of luxury shows no signs of slowing down and is stuck in a vicious cycle with the climate crisis. The more uncomfortable the climate gets for pilgrims, the more the wealthiest will be willing to pay for luxurious experiences that guarantee comfort and air conditioning, thus fuelling energy consumption and waste.

Nouhad Awwad, an Ummah for Earth campaigner based in Lebanon, states that women, the elderly and disabled pilgrims will experience the impacts of the climate crisis more severely. “The heat stress will affect them more and will put them more under danger,” she says, pointing out that traditionally, most of the pilgrims have been made up of an older demographic, above the age of 45.

“The more uncomfortable the climate gets for pilgrims, the more the wealthiest will be willing to pay for luxurious experiences that guarantee comfort and air conditioning, thus fuelling energy consumption and waste”

No matter how spiritual and transformative individual experiences of Hajj may be, it cannot be denied that Hajj is big business. The Saudi government made $10bn (£8.7bn) from Hajj tourism in 2015. In 2017, Muhsin Al-Sharif, a member of Saudi Arabia’s Committee of Real Estate and Investment, said he hoped Hajj and Umrah, a shorter ritual performed by Muslims year-round, would generate some $150bn (£134bn) annually by 2022. The numbers for this year aren’t in just yet, but Seema Aunty tells me that the Hajj Ministry made it mandatory to book packages directly through it this year, thus keeping profits that would have gone to tour companies.

Cutting out the tour companies and focusing on marketing a luxury Hajj experience exacerbates existing inequalities. Al Jazeera reported in 2017 that it cost half a year’s salary for Malaysians to go on Hajj and three years of work for Bangladeshis. Jeddah’s King Abdulaziz International Airport has a dedicated Hajj terminal, with more flights available each year. A $16bn (£14bn) bullet train between Mecca and Medina has shortened the travel time from six hours to two, and expansion plans continue to be set in motion. Nazlee Chachi tells me she was “bowled over” observing how businesses take advantage of Hajj tourism and “quite disturbed” by the quantity of food going to waste on her tour. “It felt like the Saudis were numb to what people like me would be thinking about what we were seeing. I think they felt they had to justify the price tag,” she adds.

Bolder solutions needed

While the changes that would make the most impact are in the hands of the Saudi government, initiatives such as Ummah for Earth help associate Islamic principles with positive climate action, thus getting more Muslims involved in the movement. “We decided to do this project to talk to the values of [people in the region]. In many Islamic countries around the world, it’s Islamic values that you can talk to them through,” says Nouhad. One of these values is that Islam teaches Muslims to be stewards of the Earth (known singularly in Arabic as khalīfa) and to protect it and its inhabitants. This message is key to Ummah for Earth.

Climate-positive Islamic teachings are clear: chapter seven of the Quran tells us to “eat and drink, but waste not by excess for Allah loves not the wasters”, while chapter 17 tells us not to “strut arrogantly on the earth”. Furthermore, prophetic tradition states, “conserve water, even by a flowing stream” and “whoever plants a tree, and diligently looks after it until it matures and bears fruit, is rewarded”. Collective action by Muslims, in the form of the Islamic Declaration on Global Climate Change of 2015 and the Global Muslim Climate Network, has sought to drive change on a greater level. Still, we will get nowhere without commitment and investment from the powers that be. Cambridge Central Mosque was named Europe’s first eco-friendly mosque, but the most iconic mosque in the world, the house of our God, is yet to set an example for Muslims to tread lightly and become stewards of the Earth.