Is YouTube series BKChat London an echo chamber for misogynoir and hypermasculinity?

Iman Mohamed

12 Jan 2017

Since its debut on Youtube two months ago BKChat LDN has taken social media by storm, generating hundreds of tweets every Wednesday evening and garnering over 80,000 subscribers.

The premise is simple: five young men and women sit in a kitchen and discuss topics ranging from sex and dating etiquette to religion, but herein lies its genius. The show has its finger on the pulse of London youth culture – the chemistry between the cast members and the contemporary nature of the discussions add to its appeal, making BKChat not only relevant to many young Londoners, but also extremely entertaining.

When this is coupled with the acute lack of young black British representation in media, the show offers a timely filling for that void. It is a way for many of us to see our voices and identities represented at last. The show is never one to shy away from controversy, either – since its first episode aptly titled “He Broke Up With Me At A Bus Stop!”, BKChat has been the catalyst for conversations that traverse social media platforms and continue long after the credits have rolled.

“Shortly after the episode aired, multiple tweets spanning a few years surfaced of Mimi encouraging and partaking in the racist slander of black women, also referred to as misogynoir”

However, it was the most recent episode that triggered the stormiest backlash in the show’s young history. As far as BKChat episodes go, the eighth is typical: the topic centres around performative masculinity in the form of “good guys” versus “bad guys”, Lucas passionately declares himself the manliest of all men and is met with disdain from everybody except Esther, and Gogo articulates himself well, to Biskit’s surprise. The counteraction from viewers came by way of the show’s newest member, Mimi.

Coming across as poised and measured in the episode, it is her racism-laced tweets that have many fans rightfully infuriated. Shortly after the episode aired, multiple tweets spanning a few years surfaced of Mimi encouraging and partaking in the racist slander of black women, also referred to as “misogynoir”.

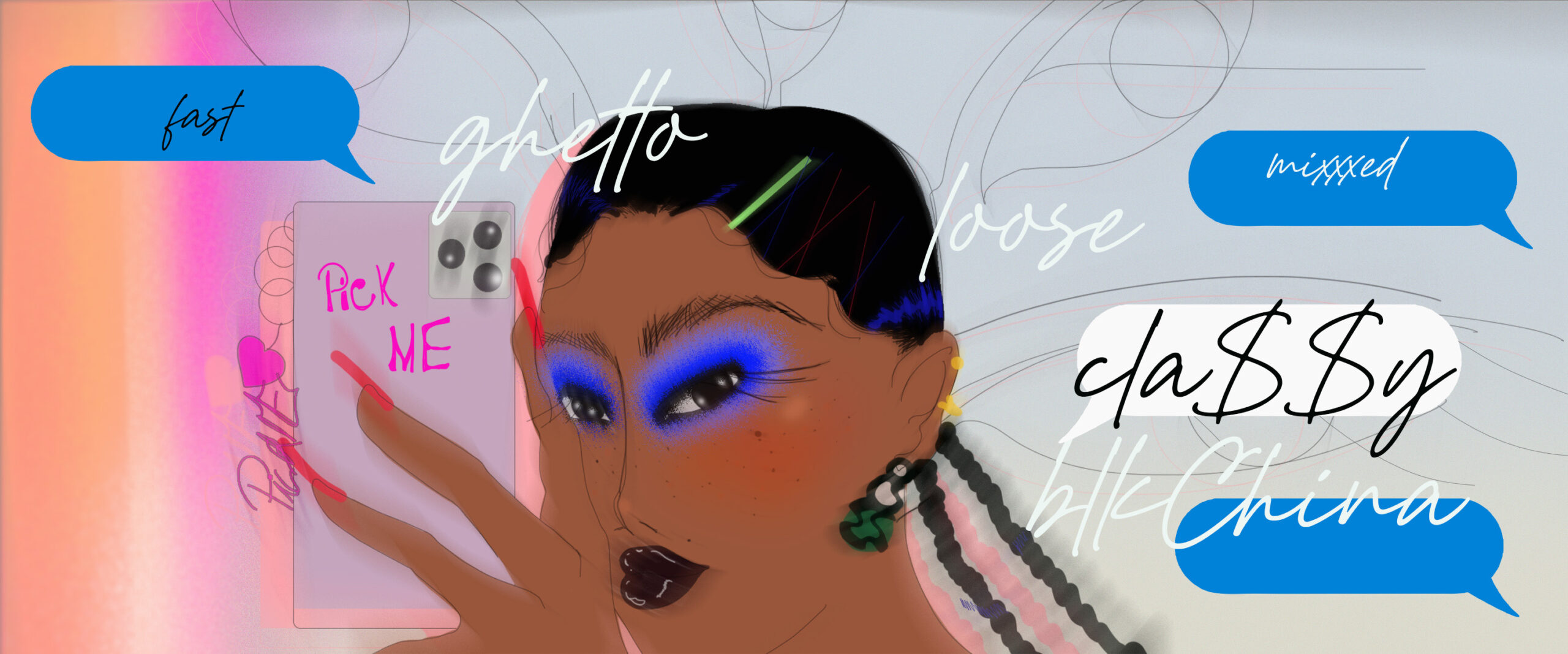

Misogynoir, as explained by Paula Akpan, is a “…word [that] encapsulates the unique oppression faced by those who are both women and black.” In her tweets, Mimi expresses her disgust with black women’s hair, describing it as a “thinned out piece of grease”, and tauntingly uses racial slurs to convey her perceived superiority to black women.

What makes this all the more ironic is Mimi’s willingness as a non-black woman to benefit from black culture when it suits her. Although not exclusively black, BKChat was created by Andy Amadi, a black man, and boasts a predominately black cast. In addition to this, Mimi has modelled for Black Hair Magazine, and featured in music videos by black artists. This blatant exploitation of black owned publications by an individual who has demonstrated her hate for black women on more than one occasion is deeply unsettling.

As a non-black woman, Mimi has profited off of her racial ambiguity and used black platforms like BKChat to get ahead in her career while simultaneously spewing vile misogynoir online. Although the show issued a formal apology, removed Mimi as a cast member, and released a last-minute episode of the remaining cast’s reaction to her tweets, many people feel that not enough has been done in unpacking just how hurtful and exploitative she has been.

This is my main sticking point with BKChat. Despite the efforts in choosing topics that will ignite lively debate, the episodes often end up becoming an echo chamber for misogyny, hypermasculinity and other uninformed opinions. I have been left frustrated and dissatisfied on many occasions by the lack of nuance afforded to weighty subjects such as cosmetic surgery, the obvious power imbalances in heterosexual relationships, and the dangerous notion that a man is sexually entitled to a woman once he has paid for the date.

“I feel that in tackling such substantial themes with nonchalance, BKChat leaves many of their complexities unexplored, and not for the better”

For example, episode two (in which cosmetic surgery was discussed) came to an end without the cast scrutinising the dismissiveness of the idea that women’s insecurities about their appearance should magically vanish with the love of a man, and there was a lack of acknowledgement of the fact that the root causes of these insecurities stem not from vanity, but from decades of social conditioning that have women believing that they will never be good enough.

Additionally, Biskit’s statement in episode three that a date with him guarantees him sex with a woman “whether she likes it or not” was disregarded, despite it carrying connotations surrounding consent. I feel that in tackling such substantial themes with nonchalance, BKChat leaves many of their complexities unexplored.

On the contrary, Danielle Dash’s piece BKChat LDN & Respectability Politics brings up the very valid argument that the dismissal of shows like BKChat usually take root in respectability politics, which she describes as manifesting itself in “calls for the cast members to behave in a manner that’s more palatable to appease the sensibilities of those prefer popular images of black people to be sanitised and acceptable to others watching”. For decades, black people in the public eye have been forced to dilute their identities in order to fit into moulds of social respectability that place emphasis on flawed ideals of intellectualism.

However, it becomes difficult to hide the disillusionment with shows like this where opportunities for fruitful discussions are frequently missed. Even when issuing apologies for behaviours deemed irresponsible, cast members have not taken the opportunity to reflect fully on the weight carried by their words. From Biskit’s apology insisting that his words were “taken out of context”, to Mimi’s, where the loss of her modelling contract took centre stage while glossing over the offence caused to black women altogether. My reservations about the show do not lie in the way that the cast members choose to present themselves, or even with their opinions, but with the fact that although rebuttals are offered to everyone’s relief, the topics are never probed to the extent to where they become educational.

Ultimately, I am a fan of the show and the concept is refreshing and much needed. However, these growing pains have revealed that although BKChat is an excellent idea, with great camera work and a vigorous social media campaign (which have been effective ways to get the show off the ground), it has a long way to go in ensuring that the topics of debate are dissected in a way that grants them the sensitivity they deserve.

In saying all this, I truly hope that the incidents over the past few weeks are a part of a process of growth that will ensure a more thoughtful approach in future episodes.