Maïté Marque

“Not like other Black girls”: Pick-Me-ism and early strategies in self-preservation

Pick-Me-ism exploits one of our most basic impulses: fear. It is both dangerous and deserving of compassion.

Soleil Jane and Editors

16 Sep 2021

So, what is the consensus, if any, on Black women wearing bonnets in public? Is it simply a personal choice with no bearing on pride, or a concerning and likely symbol of a lack of self-care? As the dust (re)settles on actress and comedian Mo’nique’s recent Instagram rant urging fellow Black women to have enough respect for themselves to leave the bonnets at home, we find ourselves back to the cyclical topic of policing Black women’s bodies out of ‘concern’.

Wherever you stand on Mo’nique’s comments, she is not the first to suggest that it is incumbent upon Black women to navigate their wardrobe choices in ways that might mitigate the harm and prejudice leveled against them. Some of the more critical responses to Mo’nique’s rant harkened back to previous accusations of her being a “Pick-Me”.

This got me thinking: what’s in the name ‘Pick-Me’? How broad and how far back does its scope reach? And what does it have to do with self-preservation?

A term first circulated and popularised within Black internet circles, Urban Dictionary defines a ‘Pick-Me’ or ‘Pick-Me-Girl’ as a girl who puts down other girls for male attention or validation. In its crudest form, it may sound like your run-of-the-mill, girl-on-girl slut-shaming. At its core, and particularly when practiced by Black women, it makes an attempt at self-preservation by participating in rhetoric that considers certain Black women – most of them, even – as having earned the harm they experience, or not having done enough to prevent it, unlike the exceptional few who are “picked” for far better treatment.

“The subtext is that, much of the logic that belies Pick-Me-ism is aligned with a self-preservation so rudimentary, even a child might seek it”

Let’s set aside the blatant infantilisation in the term Pick-Me girl, despite the fact that it emerges from and describes fairly adult themes of improving one’s stock by undermining their sexual competition. An issue in its own right, no doubt. But the subtext is that, much of the logic that belies Pick-Me-ism is aligned with a self-preservation so rudimentary, even a child might seek it.

‘Pick-Me’ may be a term used widely among adult Black women in many a Twitter thread, but the less-than-subtle undermining of fellow women for male approval, is similar to how some young Black girls make their debut to their respective corners of the internet.

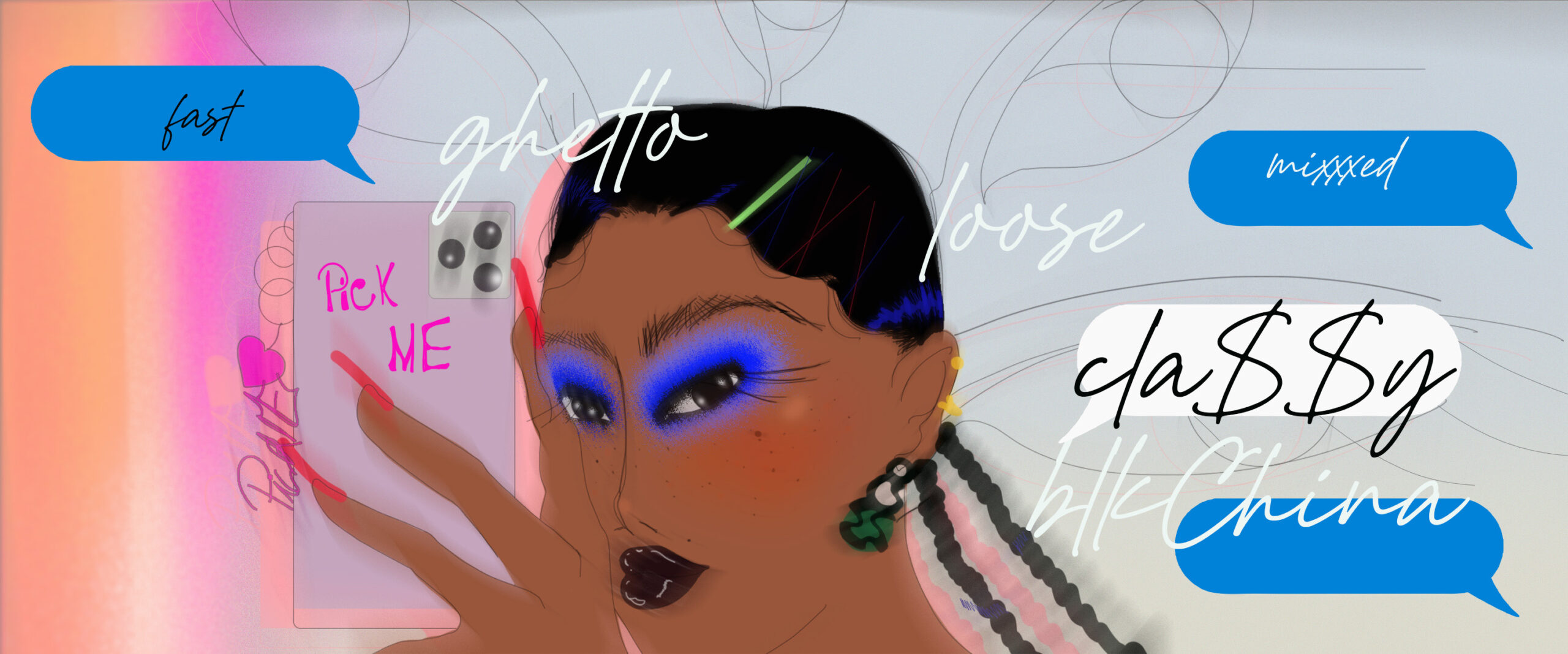

At 13, my friends and I were quickly learning of new and exciting spaces online and while new social networking platforms weren’t exactly popping up as quickly as they do today, the likes of MSN Messenger, Blackplanet, and Toronto favourite, Tdotwire, were changing our after-school catch-up routines in a big way. Cla$$y this, Mixxed that, and too many BlkChina’s to count would appear as I scrolled past an array of creative usernames and avatars with high ponytails and impressively laid edges.

My interests at the time?

Hair bobbles, matchy-matchy outfits, puppies and Sister, Sister. Or maybe I’d transitioned to Girlfriends by then. Nevertheless, when I began compiling my own creative list of possible usernames that would sum up my online persona, I realised that none of them were helping me make the kind of statement that I wanted to make in my everyday life. The kind of statement that might actually protect me from unfair assumptions that circulated about so many Black girls my age. Assumptions about us having a propensity to promiscuity for being flirtatious or having ‘no home training’ when we would succumb to emotional outbursts now and then.

“Many of us attempt to minimise our Blackness and/or shield from the risk of association with stereotypical tropes”

It wasn’t everyday I would get to create a persona and username that would tell others up front that “yes, I’m a Black girl but the respectable type”.

In coming-of-age moments just like these, where Black girls have the chance to create an ‘imaginary self’, many of us attempt to minimise our Blackness and/or shield from the risk of association with stereotypical tropes. Behind these tropes are what writer and academic Robyn Maynard calls “highly stigmatised ‘deviant’ realities, such as receiving social assistance, single motherhood, living with mental illness, and being involved with drugs or sex work”.

Looking back I often wonder, what motivated us to gesture towards stratifications of race and class when given the opportunity to showcase our actual interests as young girls?

One evening after school, I sat in front of the living room computer toiling over what my first email address should be. I’d been trying to make a decision all week and I decided that this would be the day. Trying to drown out the sound of dial-up internet, my mind wandered back to the history class I’d sat in earlier that day. One projector slide about war propaganda had some barely visible background images. Multiple signs hung on a fence that read: “Post No Bills”. Another student, like myself, more fixated on that distant detail than what the teacher was discussing in the foreground, asked, “what does ‘post no bills’ mean? The teacher sighed and responded, “it means you mustn’t post any advertisements, banners or signs of any kind there”.

“While I was afraid of being labeled unfairly, I did not want to play the game of drawing attention to stereotypical labels”

Me, exasperated and just wanting an afterschool snack, landed on “Postnobills + a random assortment of numbers + @hotmail.com”. A placeholder, I told myself, until I could think of a username that might spare me from judgement a bit more inconspicuously.

I may not have had the tools to identify what this trend was of Black girls centring their distinctness from other Black girls in their usernames, but I understood that there was a point. For example, I knew that one of the worst things a Black girl could be labeled as back then – and perhaps, still – is a hoe or a slut (“fast” and “loose” were common slangs used). For little more than the same experimentation white girls of our cohort explored, Black girls could often expect to bear the disrespect and shunning that came with it for far longer, for doing far less.

I understood why I should distance myself from the Black girls unlucky enough to get caught in the crosshairs of racist and sexist stereotypes, but I wondered who this would be empowering to. It didn’t feel empowering to me.

Of course, I didn’t want to be perceived as “ghetto”, “fast”, or irresponsible and I knew that many stereotypes beyond my control would create those perceptions in others’ minds, anyway. But what my exasperation led me to that afternoon, was admitting that while I was afraid of being labeled unfairly, I did not want to play the game of drawing attention to stereotypical labels – or, in the case of my new email address, ‘bills’ – for the sole purpose of insisting that I’m nothing like the girls who actually ‘deserve’ them.

“Pick-Me-ism is both dangerous and deserving of compassion”

As a Black woman in her thirties, only now listening intently to her inner child, I have a better perspective on what I was grappling with as I navigated one social networking platform after the next as a teen. I can also hold space for a nuanced understanding of Pick-Me-ism in that it exploits one of our most basic impulses: fear. It is both dangerous and deserving of compassion.

Early strategies that many Black girls take on to get ‘picked’ (exempted) – if only imaginarily and temporarily – from the harshness that often visits Black girlhood, can be as innovative as they are draining. What is constant, however, is that they centre fear, not agency nor genuine interests.

When getting ‘picked’ is aligned with only conditional safety and respect, we could move as strategically as we want to, and even feign concern for Black women and girls who choose not to, but we have to know and name fearful responses to misogynoir as we experience them. Past and present.