A brief history of Islam and hip-hop, from DJ Kool Herc to Alia Sharrief

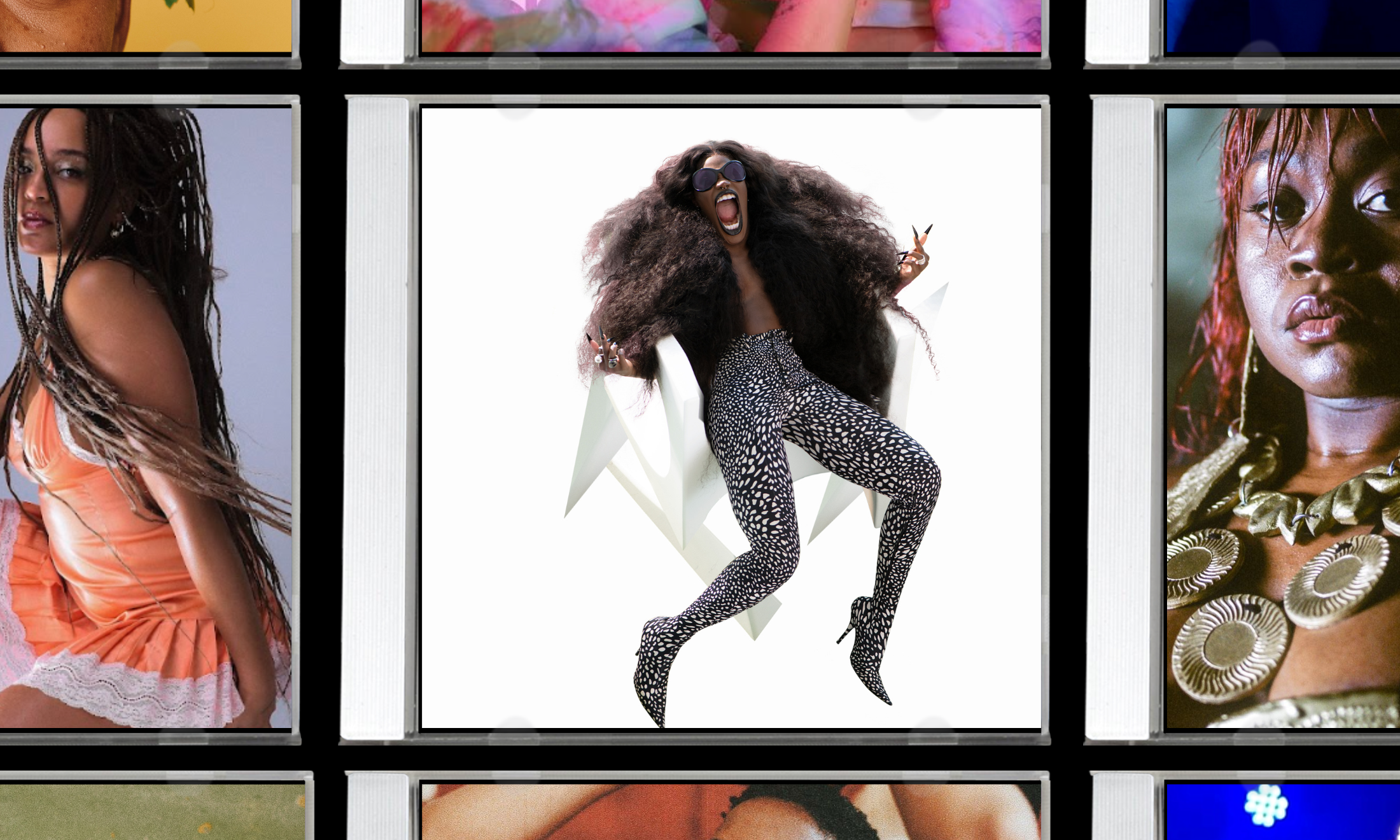

Rihanna’s SavagexFenty show came under fire this year for playing a remixed version of a Hadith. While it is perfectly understandable to be offended by the misuse of important Islamic literature, many failed to see the connections that have existed since hip-hop’s conception.

Muna Ahmed

11 Dec 2020

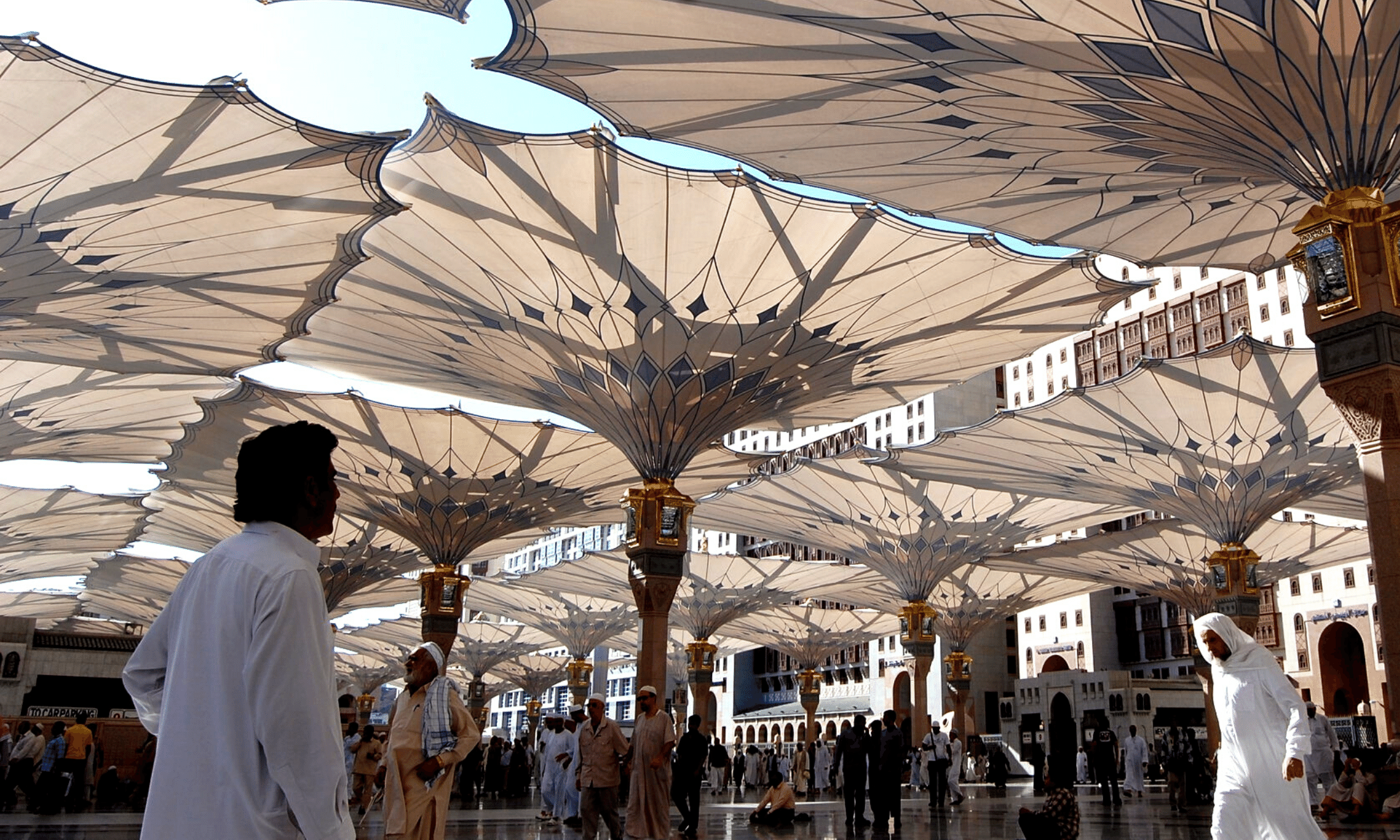

Islam and hip-hop image, L-R: Miss Undastood (c: album artwork), Alia Sharrief (c: YouTube), Jay Electronica (c: Wikimedia Commons) and DJ Kool Herc (c: Wikimedia Commons)

The story begins in the birthplace of hip-hop, New York City. More specifically, 11 August 1973 in the Bronx. Eighteen-year-old Jamaican immigrant Clive Campbell is throwing a string of increasingly popular block parties, exposing inner-city partygoers to his native bass and dub sound.

Unbeknownst to Clive (otherwise known as DJ Kool Herc), or those around him, his experiment on this night – playing the same record on two tables simultaneously, then repeating the break – birthed the notorious “breakbeat” style that laid the foundations for the landscape of hip-hop. He was making history and redefining music forever. After Kool came Grandmaster Flash, whose “quick-mix theory” perfected the breakbeat by placing markers on the record at the exact points where the break begins and ends. Finally, came Afrika Bambaataa, credited with perfecting the genre.

These three DJs, known as the “holy trinity” founders of hip-hop, are widely credited for pioneering the genre – although Afrika’s legacy has recently been rethought after allegations of child abuse were levelled against him. What’s perhaps less well known is that two out of three of them – Kool and Afrika – personally studied the teachings of the Five-Percent Nation, a movement influenced by Islam. They incorporated enough of these studies into the genre to prompt Professor Felicia M Miyakawa to write a book on the subject in 2005, Five Percenter Rap: God’s Hop Music, Message and the Black Muslim Mission. These young musicians found a voice in hip-hop. As historian Paul Gilroy wrote in his 1993 book The Black Atlantic, the genre was “the powerful expressive medium of America’s urban black poor […that] created a global youth movement of considerable significance.”

“Hip-hop helped introduce Malcolm X to young people and Malcolm X helped introduce young people to Islam”

Odes to Islamic figures like Louis Farrakhan, leader of the Nation of Islam – a political and religious movement dedicated to improving the spiritual, mental, social and economic condition of African-Americans – helped fans tap into the movement. The 1980s and 1990s saw Farrakhan name-checked by the likes of Nas, Biggie and Big Daddy Kane.

It was filmmaker Spike Lee who suggested Malcolm X was a significant figure in spreading Islam to Black youth, saying that, “hip-hop had a lot to do with introducing Malcolm X to the young people. It was through the music of Public Enemy, Chuck D, through the music of Boogie Down Productions.” He was spot on. Hip-hop helped introduce Malcolm X to young people and Malcolm X helped introduce young people to Islam. Through this integration of African American culture and political struggle, hip-hop became a symbol of cultural Blackness in the USA. Black Muslim women ran with this and incorporated their own struggles into the genre. From Miss Undastood, the first Black Muslim woman rapper, who prides herself with infusing hip-hop along with Islamic messages, to hip-hop artist and human rights activist Alia Sharrief who names Islam as her greatest influence.

The story continues in São Paulo, the heart of Brazil’s Muslim hip-hop movement. Many Afro-Brazilian social movements in the 20th century were characterised by political hip-hop groups including The Black Panthers of São Paulo, a Brazilian hip-hop posse inspired by Muslim hip-hop in the US, and Posse Hausa, another hip-hop activist group named for an ethnic group in West Africa who believed Islam-inflected hip-hop would draw attention to racial inequality.

The focus of Afro-Brazilian social movements in São Paulo is in stark contrast with those in Rio where baile funk – a genre both criticised and revered for its authentic expression of sexual freedom in Afro-Brazilian society – originated. More recently, the genre sparked controversy when, earlier this year, Rihanna came under fire following US rapper Rico Nasty’s dance at the SavagexFenty lingerie show.

The performance was set to a remixed version of a Hadith – one of a collection of recorded sayings by the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) that account for the majority of moral guidance for Muslims outside of the Qu’ran. London artist COUCOU CHLOE, who produced the track used a Hadith explaining the signs of the day of judgement, later claiming she had collated random baile funk samples with no clue as to their significance.

“In the rush to insist Islam and hip-hop music should be entirely separate, many failed to see the connections that have existed since the genre’s conception”

Perhaps this seemingly misjudged sample choice is really a manifestation of a preexisting cultural and historical link. In the rush to insist Islam and hip-hop music should be entirely separate, many failed to see the connections that have existed since the genre’s conception. And while it is perfectly understandable to be offended by the misuse of important Islamic literature, it is likely the significance of the message was simply lost in translation.

Marginalised communities in the US, Brazil and beyond were attracted to the spirit of revolution in the hip-hop movement and found parallels in their fundamental beliefs. With a focus on social justice, spiritual enlightenment and knowledge of self, Islam offered new means for resistance and liberation to these communities. As a Muslim woman, these parallel themes are what attracted me to hip-hop music of the late 80s and early 90s.

Now, as hip-hop has moved away from its Islamic roots, recognition of its foundational themes has dwindled, with Arabic words and invocations being used for style rather than substance. One contemporary rapper who’s been known to maintain authentic spiritual lyricism through his work is Jay Electronica. His 2020 debut album, A Written Testimony, is dotted with Islamic references throughout. Jay has never shied away from showcasing his relationship with Islam in his music – in fact he centres it.

After all, they are both a way of life. As legendary MC KRS-One once said: “rap is something you do, hip-hop is something you live.”