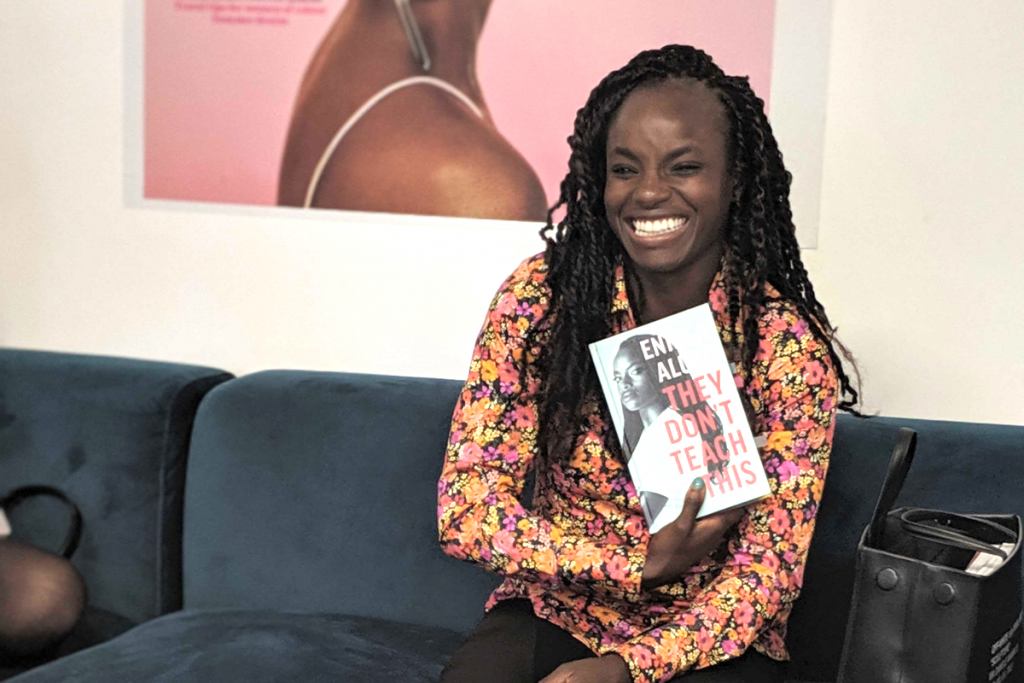

‘I’ve been through things in life other footballers have not’ – why Eni Aluko is goals

Charlie Brinkhurst Cuff

05 Sep 2019

When professional footballer Eni Aluko makes her way to the gal-dem offices on a breezy summer afternoon, she is in a serious mood and more than ready to talk about her new book, They Don’t Teach This. “I just spent the morning doing media interviews and it’s teaching me how they think,” she sighs. “Ultimately I’ve written a whole book about my life for a year, but the mainstream media want to box you into one event, that case, that moment. They can’t see beyond that.”

Long before you get to the portion of the book on Eni’s widely-publicised discrimination case against The Football Association (FA), They Don’t Teach This has a lot to give. From her dual upbringing as a British-Nigerian and finding her feet as part of an immigrant family, to thrilling descriptions of wins against Notts County and losses against Manchester City, it’s a solidly-interesting tale of an extraordinary life. Born in Nigeria, but moving to the UK when she was a baby, Eni was a precocious footballing talent who grew up playing with the boys on her estate in Birmingham.

She was picked for the England team as a teenager and continued through their ranks, but in this (deceptively recent) era of women’s football, nothing was guaranteed. She decided to train as a lawyer, balancing her coursework with her footballing commitments. After graduating, she was instrumental in England’s women footballers getting some of their first paid contracts.

“Eni Aluko’s book is a solidly-interesting tale of an extraordinary life”

Of course, her memoir does go into emotional detail about her case against the FA. As widely publicised in 2017, she was the victim of racist remarks from the former England women’s team manager Mark Sampson, who suggested that her family might have Ebola and eventually let her go from the England team – despite her being the women’s league’s top scorer. But what the book manages to do, far more than any articles written on the topic have, is lay out the development of their tumultuous relationship in a way that will sound familiar to many black women who have been accused of being too “aggressive” or forthright. Mark became her “adversary” not just because of a couple of isolated incidents, but because of a pattern of behaviour over many months which was then systematically supported by the FA.

Apart from this, one of the main takeaways from the book is that the footballer is tenacious and furiously hard-working. Now, she wants to impart the knowledge she has been lucky enough to gain – to tell black women to get an education, to aim high. Although at points you can see how her tendency to want to support others has made her life objectively harder, it’s a reminder that despite all that she has been through, her main goal in life is to change things for the better.

Why did you want to tell your story through the medium of a book?

Eni Aluko: I’ve been through a lot in a short space of time and my life’s been very colorful and eventful – both positive and negative. I was confident I could create something that was actually meaningful, beyond just talking about football or how many trophies I’d won. That’s the stuff that you talk about in every article or in every interview on every Sunday after a game. I’ve been through things in life other footballers haven’t.

In the book, you tell a story of going to Nigeria age 12 to see your dad being elected to high office as a politician. What was it like to revisit those memories?

Eni: It was a bad experience. It affected me negatively at a time when I was accepted as this Brummy girl – a tomboy that was in with the boys as a footballer. So if I was going to extend my identity to anything else, it better be good. When I opened my mouth everyone was challenging me on my Nigerianess. I had to lie about playing football because it didn’t fit into what women were supposed to do. I thought, ‘This is not my home.’ I wondered why it was so challenging to be Nigerian? So, I shut that part of myself off and was okay with the British part, the part that played for England. It was later on in life that I was reminded I was Nigerian. Like Mesut Özil, who plays for Arsenal, famously said [when he quit his international team], ‘I am German when we win, an immigrant when we lose.’

I know that since then you’ve visited Lagos and it’s now a place that you really love. What did you discover about Nigeria that made you come to love it?

Eni: I went to Brunel, which is a very multicultural uni. Within three days I’d met all these amazing Nigerians. We had such amazing conversations and I was able to understand Nigeria from their perspective. It awoke something inside me. We had cookouts, ate jollof rice and shared our faith. Then my family moved back to Nigeria. I thought, ‘Okay, now I can call it home’. Lagos is one of my favorite places now. It’s a melting pot; the buyer of Africa. There’s a great culinary scene and an energy. My brother [footballer Sone Aluko] chose to play for Nigeria, ahead of England. It was a surprise because, like me, he didn’t really have a relationship with Nigeria growing up. I thought he was less Nigerian than me! But now, as a result, he has a foundation there. Your relationship with your home country can start at different times in your life. Once that connection is made, it’s so strong. But that initial journey to get there is hard.

One of the things I’ve noticed recently is there seems to be a bit of a change in the way that West Africa and particularly Nigeria is being perceived.

Eni: It’s become so cool. I went to a predominantly white school and had a lot of friends. I didn’t have any problems with racism. The girls that picked on me were Caribbean. They called me a coconut because I spoke well. They’d say, ‘You’re an African bhutto, you’re fresh.’ Now, it’s associated with Afrobeats and Wizkid. I tried to get the Nigerian football shirt last year and it sold out!

As you write towards the end of the book, your life has very much been one of extreme lows and extreme highs. Do you think football led you down that path?

Eni: I think football led directly to that. It’s a profession where there’s a lot of adoration for what you do. As a striker, it’s very much the case of scoring goals and everyone loving you. But there’s big dips as well. With success always comes opposition. So as I’ve gone through life, the more successful I’ve become, the more I’ve seen that people don’t like you. People are jealous. People only want to see you in a certain light because that’s their projection of what you are as a black woman. As British Nigerian, there’s stereotypes. Success is just half the story, it’s dealing with success. They don’t teach this because it’s unspoken. There’s no right way of figuring it out. But, starting conversations is really important.

Do you think footballers need more support in terms of their mental health?

Eni: I think there’s a kind of bravado in football that’s like, ‘You should be tough. You should deal with that. We’re athletes.’ I actually think a session with a psychologist at least once a week as an athlete should be mandatory, in the same way that you eat carbohydrates and protein.

Being a pundit, you have an intimate understanding of the media. But then, on the opposite side of that, you’ve received very bad treatment from them as well – the Daily Mail once published a naked picture of you. How do you balance that?

Eni: It’s a weird one because I am the media in some aspects, even though I only talk about football games. But on the other side, I’ve very much been a victim of the media. It’s a double-edged sword because as a public figure you need the media. No-one would know about They Don’t Teach This if I didn’t have the media, but at the same time, I think mainstream media ignores the substance of what people can learn from. We’ve got to get to a point where we stop putting ourselves in boxes and stop allowing other people to put us in boxes and embrace all of that. I’m not just a footballer, I’m a lawyer, I’m a media pundit, I’m an author, all of that.

I’m sure you’ve been asked this a million times, but why do you think representation is so important for young black women?

Eni: In politics, in sports, representation is important because the people that make decisions make them on the basis of their experience. Beyond buzzwords like diversity and inclusion, it’s just good process to have better representation. I also think it’s really important to be able to visualise your aspiration. If you can’t see what you want to become, it’s very difficult to become it. Growing up as a footballer, apart from the Williams sisters, I didn’t see any black women in sport. Women’s football wasn’t even on TV. So I latched onto the Williams sisters because it made me feel less weird. I’ve had to become a pioneer for young black girls in football and the media.

You mentioned the fact that you were sad that some of your teammates towards the end of your relationship with the FA weren’t more supportive. What do you think they would think of the book in general?

Eni: I think they’ll be uncomfortable because I’m calling them out. But at the same time, I’m able to reflect and say they were in a difficult situation too. They were lied to. They were told that ‘Eni Aluko is lying’. They were told that I was doing all of this to derail their European championship campaign. What they could have done is texted me or called me to say, ‘What’s going on?’ But in that moment, people made mistakes, including me. So I’m able to appreciate that it was difficult. But I think ultimately they’ll be remembered for not speaking up when they could have. They could have made a statement about racism at the very least. I didn’t need people to necessarily back me, but support the stance. That’s what really disappointed me because I think when the shoe had been on the other foot with teammates, I’d always backed them. I remember one of my teammates desperately trying to get out of her contract, and I spent two hours on the phone with her saying ‘Okay, do this, say this’. I was happy to help. I think that when I look at other teams, they’ve done better at supporting their teammates.

In the epilogue of the book, you talk about coming face-to-face with some of the people you had challenging experiences within the upper echelons of the FA. You’ve done that now. Is there anything left to be afraid of?

Eni: I’m not afraid, but I don’t know what the future’s going to hold. I’m glad that I’ve closed that chapter. But I feel like, in terms of forgiveness, God put that test in my life. With all of the people in the FA, Mark Sampson, the coach – and I mean this with sincerity – I’ve moved on from it. I can still address it, which the book has done, and say, ‘That was not right.’ But I really hope that comes across in the book and that as much as possible, people don’t try to frame it as ‘them against them’, because that kind of headline-grabbing is not reality.

You’re now in Italy, with Juventus. What are you hoping to achieve with them?

Eni: The first year with Juventus was very successful and I ticked all the boxes. Going into my second season with them I want to achieve as much as I can. But I think it’s probably the last phase of my football playing career.

How does that make you feel?

Eni: It’s sad, but the reality is you can’t play football at this level forever. My body niggles more than it used to. My mind is tired. But there’s so much more beyond football that I can do. So, watch this space. I don’t know what the next six months is going to hold, but I know that whether it’s playing or whether it’s off the pitch it’s very exciting.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity