Jamaica Kincaid sees the world in the garden

As five of her works are re-released, the writer sits down with gal-dem to discuss what plants can teach us about ourselves and why she’ll never tire of growing.

Aimée Grant Cumberbatch

16 Jul 2022

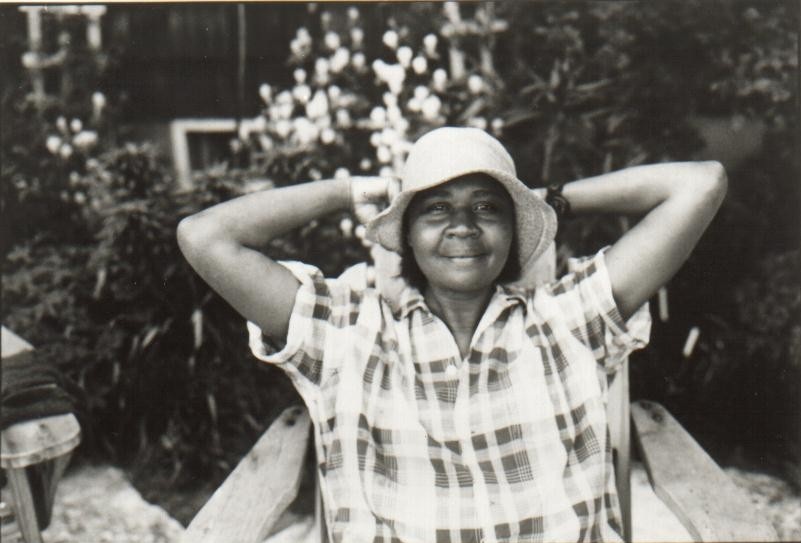

photography courtesy of Jamaica Kincaid

Jamaica Kincaid doesn’t appreciate Zoom self-view. “I hate the way I look on Zoom… I never look at myself.” I can relate. I think this a few times during my call with the author. Like when we’re interrupted by the dentist ringing to check whether Jamaica will attend her appointment on Thursday, or when I find out she has just come in from the garden where she has been plagued by a pest. But it is best to resist wrapping her up in a neat bow – she is many things, not all of which can or should be labelled ‘relatable’.

As well as a novelist and professor of African-American studies at Harvard University, Jamaica is a gardener and gardening writer. She was born and grew up in Antigua. In 1966, aged 17, Jamaica’s mother sent her to the United States to work as an au pair. While there, she took community college evening classes, later quitting her job to study film at university, before quitting that, too.

By the early 1970s, she had moved to New York, changed her name to Jamaica Kincaid and begun writing for magazines including the New Yorker. She has since written more than a dozen fiction and non-fiction books. Her garden in North Bennington, Vermont is the subject of My Garden Book and gathering seeds for it is the object of her adventures in the memoir Among Flowers. Jamaica has been writing about what it means to garden while Black since the 1990s, preparing the ground for new works like Claire Ratinon’s Unearthed: On Race and Roots, and how the Soil Taught Me I Belong and Flock Together: Outsiders by Ollie Olanipekun and Nadeem Perera.

This summer, five of Jamaica’s works have been reissued by Picador, and five more will follow in 2023. When I ask how she feels about this, she says: “Stunned. It’s something I would not have expected. Those books seem [to be] written by another person. Sometimes I look through them and think, was I really that intelligent? I feel very grateful. But also I think, am I dead? This [reissuing] only happens when you’re dead.”

“When I’m alone in the garden, we are speaking to each other”

Jamaica Kincaid

Kincaid is very much alive and eagle-eyed. She notices a monstera in my living room and jokes about “your generation’s” interest in houseplants. It sets us off discussing the truthfulness of plant categories. She notes: “In your climate, [the monstera] really belongs in a house. In my climate, it’s all over the place.”

She sees these categories as an expression of human beings’ seemingly insatiable need to order. “[It] haunts me,” she says. “It’s no longer an interest, it’s an obsession. The imposition of the order is to help you get through the day and get through your life. But we don’t stop there. We impose it on the rest of the world that we can impose it on. Especially in the garden, [I wonder] where do you draw a line? Where do you say this is enough?”

We’ll return to ordering and imposition later, but first I ask her what she’s growing. She plays it down, but the answer is lots. Jamaica describes pink prairie rose, clematis, echinacea, balloon flowers, California poppies and Naked Ladies, naming the multiple aliases of each flower with enjoyment.

You can see snapshots of Jamaica’s garden on her Instagram @virtuouspomona (pomona is the Roman goddess of fruitful abundance). She posts pictures of produce baskets brimming with plump, shiny tomatoes and bunches of herbs; of vibrant flowers with captions like: “a cultivar of the North American hibiscus, part of the mallow family, which for me involves so many conversations, in which I speak to many selves” and of a plank of wood with nails sticking out of it that she has placed in front of the Black Lives Matter sign on her lawn, after it was run over.

Jamaica appreciates the garden’s character, and its willfulness. She describes it as telling her about herself, as gently mocking her and frequently thwarting her. “When I’m alone in the garden, we are speaking to each other,” she says. “I’ve noticed that a lot of plants I seek out invariably are taller than the literature says they should be. And because they’re taller, they stoop and they look just like me.” Jamaica is six foot tall. She tells me: “I think [the plants] are trying to mimic me.”

Gardening and failure go hand in hand and this, too, is something Kincaid delights in. “I can’t get the garden right,” she says. “And I think I like that the most. I would just lie down and die if I got it right. [Because] then it would be finished.” She describes the devastation wrought by a woodchuck with woe and wonder: “I bought some poppies. Disaster! We had a very cold spring, so I was late getting them planted. I finally put them in the garden and a woodchuck came and ate all of them.”

“All these things that were part of my childhood imagination were interwoven with empire, and the empire is violent and political”

Jamaica Kincaid

Having dreams shattered by pests is something many gardeners have experienced but, for some of us, the complications of growing go deeper. Plants are bound up in the slave trade, and knowing this can add a heaviness to gardening for Black people especially. For the British Empire, plants have meant profit. At sugar cane, cotton and tobacco plantations in the Caribbean and the US, those profits were built on the suffering and brutalisation of enslaved people.

In the 1950s and 1960s, when Jamaica was growing up in Antigua, cotton was the country’s main crop, along with sugar cane. Having now lived in the US for decades, where cotton is emblematic of the country’s shameful history of enslavement, Jamaica has an understandably complicated relationship with the plant. She says: “I grow cotton. I never get any fruit, but I love the flowers. It’s just like a hibiscus but I think it reminds me of my childhood. Every year, I have some grief with it and I will sometimes say ‘it’s clear that I’m not meant to grow cotton as amusement. It’s forbidden that a Black person should grow cotton just because she loves the flowers’.”

Gardening history intrigues and troubles Jamaica. She sees the garden as a microcosm of the world – a window into humanity’s best and, more often, worst impulses. “All the plants that I was familiar with in Antigua were not Antiguan at all. They came from somewhere else that’s part of the British Empire.” She cites breadfruit as the perfect example, telling me: “[It] was sent to the West Indies to feed slaves because they took too much time growing their own food, when they could be making money for their masters.”

She names even more plants, explaining: “The tamarind, the mango, hibiscus… all these things that were part of my childhood imagination were interwoven with empire, and the empire is violent and political. Plants led me into this world of possession, immorality, crossing boundaries. It’s very interesting how the language or the knowledge of plants are interwoven in the world after 1492.”

Jamaica has short shrift for institutions like Kew Gardens which have attempted to rewrite or ignore their discomforting histories. Since summer 2020, the organisation has, belatedly, begun to recognise its roots in colonialism. She calls the presentation of Kew as a garden “amusing”. She explains why: “In fact, it was started as an extension station – you send a bunch of plants there and redistribute them to different parts of the empire. I [own] a book about Kew and how it has transformed itself into a kind of saviour of the world. I find that so ironic because you could say it was one of the places where the destruction of the world was harnessed.”

Jamaica is still learning, she happily admits, as we discuss whether it’s harder to learn to write or learn to garden, she says, “I like my ignorance for this reason: it means I have much to learn. I don’t mind being called ignorant at all. I think, ‘I can learn this’. I really enjoy not knowing so I can know.”

Since being in her Vermont home, Jamaica has gardened there for over 30 years and this love of learning keeps her growing, season after season. “I can see the same garden every day for the rest of my life, because you learn something, you’re engaged in something in a way that I can’t find in anything else.”

It’s time for me to leave Jamaica to the rest of her day and to her garden. As we say goodbye, she looks outside and says: “It’s going to rain later, but we can do a little more gardening in between raindrops. That’s all it is – just drops.”