Discovering my great, great grandfather, one of the first West African graduates of medicine in the UK

Decolonising Healthcare columnist Annabel Sowemimo has spent this Black History Month getting to know the fascinating story of her relative, Dr John K Randle.

Annabel Sowemimo

29 Oct 2020

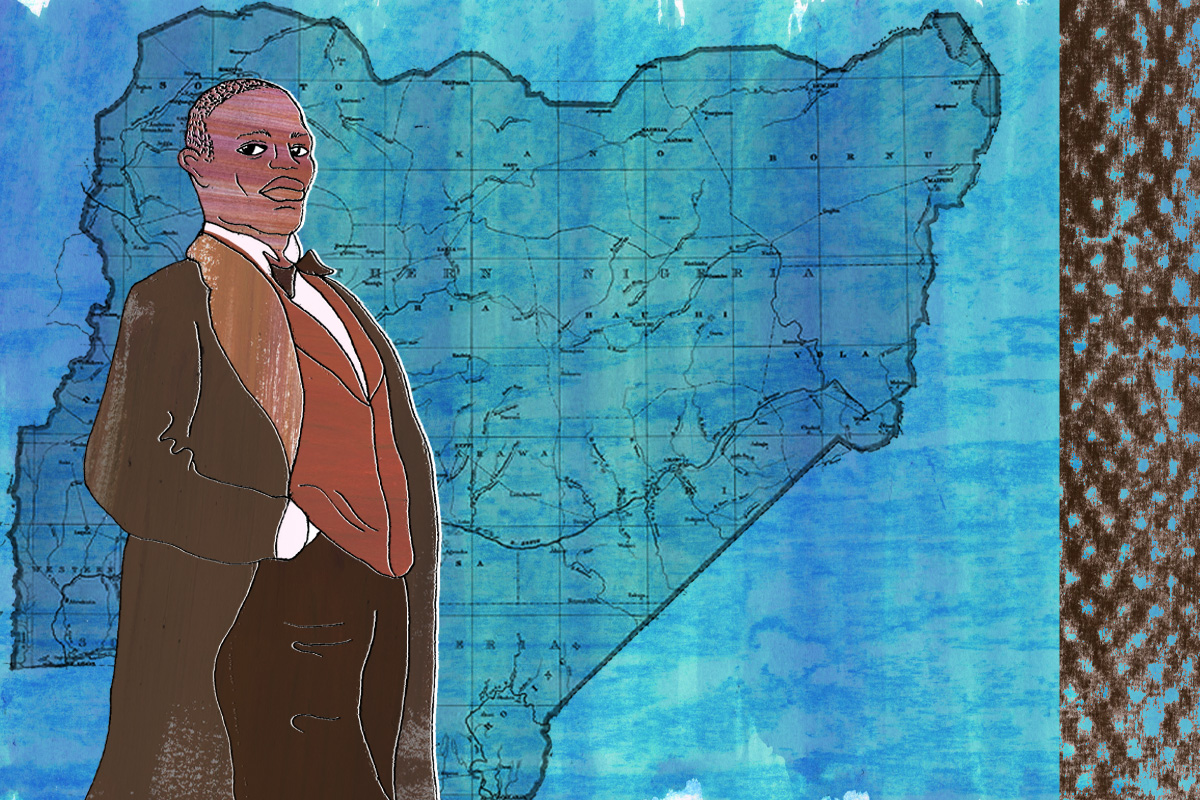

Illustration by Tessie Orange-Turner

I have mixed feelings about Black History Month, like many other Black people. However, I do celebrate that we have a month dedicated to Black contributions to history. It gives young people an opportunity to look beyond the limited scope of their school syllabus; seeing a more diverse array of programming and learning the stories of the many Black people who have contributed to Britain.

My own great-great-grandfather Dr John Randle was one of the first men of African descent to obtain a medical degree in the UK. Being born in Sierra Leone to Thomas Randle, who was a liberated enslaved person of Nigerian descent, John was schooled in Nigeria before eventually travelling to Accra, Ghana to work as a medical dispenser.

My great-great-grandfather saved for several years so that he could move to the UK and study medicine. Eventually, with the help of his supervisors, he travelled to the University of Edinburgh; graduating in 1888 with a gold medal in medicine. He then moved to Lagos, Nigeria to treat many of the colonial forces occupying the country at the time.

At about 13, I found an essay competition in The Voice newspaper which asked young people to write about a Black person who had contributed to Britain. I didn’t win but I wrote about Mary Seacole, the British-Jamaican Nurse who made an invaluable contribution to the Crimean War between 1853 to 1856. She did this by starting the British Hostel to care for injured British soldiers.

Until recently, her contributions to nursing were grossly overshadowed by Florence Nightingale. But in 2004 she was voted one of the hundred top Black Britons and after a 12-year campaign, a statue of her now stands outside St. Thomas’s Hospital in London.

“In a quest to celebrate Black history on a grand scale many people, including myself, often neglect to delve into their own families’ stories”

While I think it’s about time that we revamp our curriculum and that Black History becomes part of history – with balanced perspectives, contributions and arguments – I understand that until that is achieved BHM plays a vital role in ensuring Black perspectives are included in history. However, in a quest to celebrate Black history on a grand scale many people, including myself, often neglect to delve into their own families’ stories.

Despite Black doctors like myself making up a small proportion of the NHS, Black people have been migrating to the UK to study and work within our healthcare system for almost 200 years. My grandmother – Agnes, has often spoken about the achievements of her grandfather with a huge sense of pride. While she has always told me pieces about his life, like many families, his story is far more complicated than the details written in history books.

On John’s return to Nigeria, he became the assistant colonial surgeon. However, despite, the accolades he had been awarded abroad he faced discrimination and was not be paid the same salary as his European counterparts. On realising this he refused to continue doing tours and was dismissed from his responsibilities in 1893.

He went on to co-found the People’s Union in Nigeria – the first political party in Nigeria which promoted the welfare of its citizens regardless of race or religion. One of its main oppositions was to the water tax levy which involved taxing all citizens for piped water whilst its main beneficiaries were wealthy Nigerians and Europeans living in the city. However, its membership still encompassed the Lagos elite. He went on to marry Matilda Davies who was the eldest daughter of Sarah Forbes Bonetta Davies, the “gifted” “god-daughter” of Queen Victoria. This then afforded him the opportunity to establish his own independent practice.

While his life focus appeared to be on his clinical practice for colonial forces and his political endeavours, he did publish a few academic papers in one of the most prestigious medical journals – one on guinea worm and another on cancer amongst the “African creoles”. In the latter paper, he challenged previous assertions that the lower incidence of cancer amongst African creoles compared to native Africans was due to their lack of civilisation but rather, due to the fact they did not access hospital services.

“Dr J Randle is one of a few Black Victorians who managed to overcome both racial and colonial barriers to acquire a medical degree”

Dr J Randle is one of a few Black Victorians who managed to overcome both racial and colonial barriers to acquire a medical degree. Others include Benjamin William Quartey-Papafio who graduated from St Bartholomew’s Medical School in London in 1882. He was the first graduate from Ghana (then fondly known by the British as the Gold Coast) to earn a medical degree.

Women were not permitted to study medicine at this time until and the rules did not officially change until 1877, in part thanks to a successful campaign by seven women. For those that are both Black and women – the journey for equal opportunities within medicine continues. It was only as recently as 2005 that Samantha Tross was appointed as the first Black woman orthopaedic surgeon in the UK. While it’s an incredible achievement, it is a shame that we are still experiencing so many firsts over 150 years later.

On a surface view, examining Dr J Randle’s achievements and lifestyle may seem a world away from my own existence. He served as a colonial surgeon as part of the British Empire while I today examine how we may decolonise our healthcare system. However, exploring his life continues to help me understand who and what contributed to the current health system that we have established.

Although I have few of the facts about his life, it appears that our aims were not so different. He sought to ensure that those of African descent have access to equitable healthcare, and so do I.

Tracing your own history also serves as a reminder of how much one individual can change a family for generations for good or bad. It is a reminder that the histories of Black Britain’s are a rich tapestry – colourful and complicated. I hope that my own descendants will be able to look back at my work, learn from it and try to build a more promising future.

*This article was amended on 25 July 2022 to state that Dr John Randle’s name was written as such. An earlier version mistakenly identified him as Dr John K Randle.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?