Jonathan Borba via Unsplash

Why endometriosis feels like a battle with your own body

This Endometriosis Awareness Month, one writer explains her unending journey with the chronic health condition.

Sarah Harris and DiyoraShadijanova

22 Mar 2021

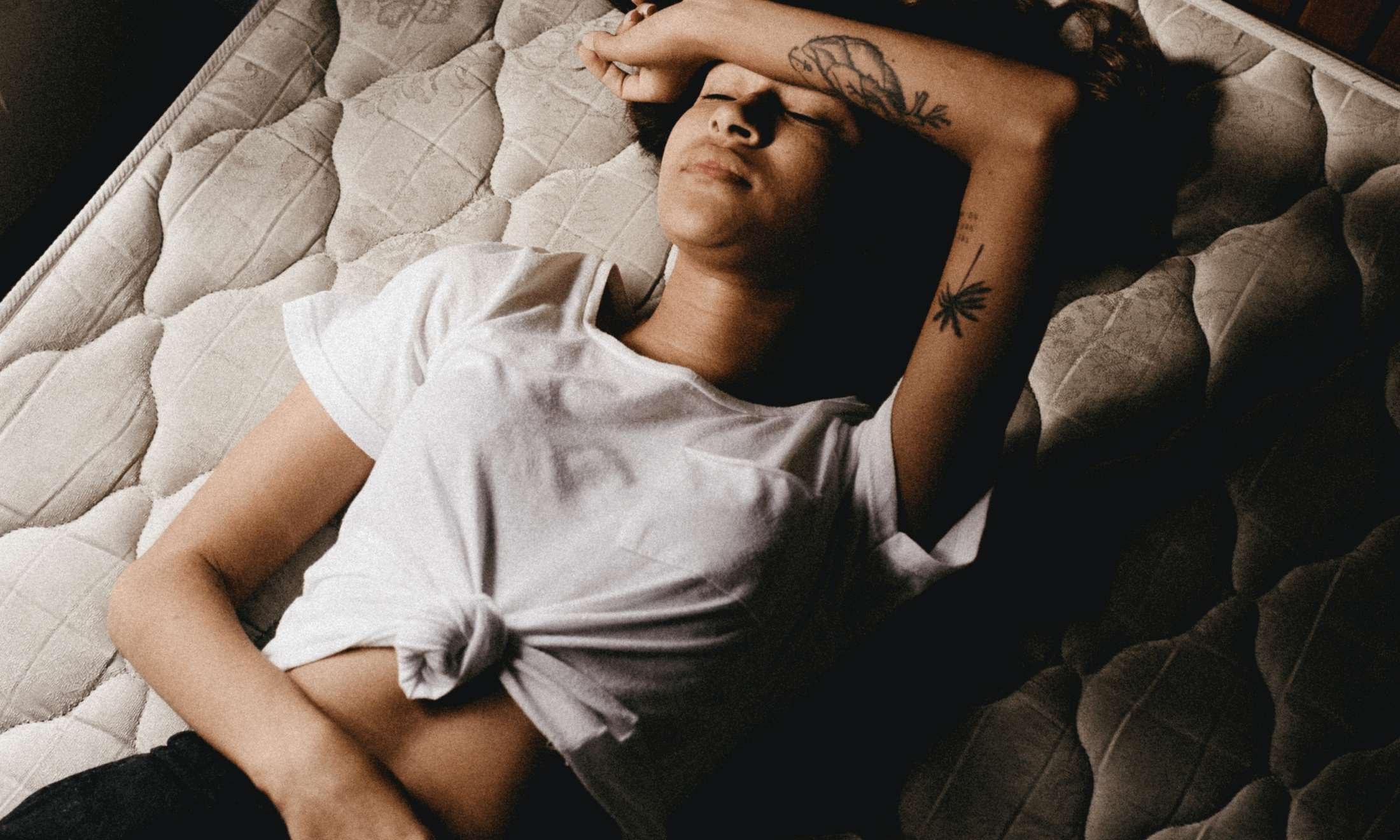

It’s 3 AM on a Thursday morning and I’m sat in bed with a hot water bottle pressed against my stomach. Every few minutes, I scrunch up into the foetal position and clench on to my duvet as a sharp pang of pain radiates through my pelvis. It’s 2 degrees outside, but the constant hot flushes that come as a result of my hormonal treatment make me feel like I’m in a desert. I feel like I need to throw up, but my body aches too much to move. This is endometriosis. This is my life every single month.

I was nine years old when I first started my periods. Even in primary school, I have several memories of bleeding through my school uniform and awkwardly asking the teacher if she could call my mum and ask her to bring a clean one in. Through secondary school, the symptoms worsened. Missing school became a monthly routine. Every few months, my parents would rush me to A&E, in fear my appendix had burst, or I had some form of severe stomach bug.

At the age of 12 I heard a doctor take my parents aside and tell them, “It’s all in her head.” After that, I assumed that the pain and discomfort that came with my monthly cycle was just something I’d have to deal with. Wasn’t this something everyone who menstruates experienced? And maybe I just wasn’t as strong as them? So, for years I subdued my feelings, smiling through the pain when I was out and making sure I doubled up on the thickest pads.

“For years I subdued my feelings, smiling through the pain when I was out and making sure I doubled up on the thickest pads”

But a few days into my second year of university, that changed when I started a period that would go on to last for six weeks (and eventually six months). By the second week, I was going through a pad an hour and the bleeding was so heavy that I could barely leave the house without leaking. Every few days, I would attend the walk-in service at my GP clinic, and I was always met with the same response – “Come back next week.”

By the sixth week, I had enough and demanded that my GP do something. He sent me to the emergency gynaecologist that day and I was told to come back in a week’s time for an ultrasound scan.

“Do you know what endometriosis is?” asked the ultrasound technician as she inspected the screen in front of her. I had only come across the condition a few months prior, when I found out a family friend had been diagnosed with it. I gave her a vague response and she handed me a sparse leaflet with the words ‘endometriosis’ boldly written across the front. And just like that, I had endometriosis.

It’s now been almost five years since my diagnosis. I’ve had every hormonal treatment possible, from the pill and IUD to a chemically induced menopause. I’ve had two surgeries and still, none of the treatments have worked. I’m in pain most days, despite the fact that I haven’t had a period in almost three years. After all, endometriosis is a chronic condition and there appears to be no hope for a cure any time soon.

“I’ve had every hormonal treatment possible, from the pill and IUD to a chemically induced menopause. I’ve had two surgeries and still, none of the treatments have worked”

I always assumed that receiving a diagnosis, after over seven years of suffering would provide me with some much-needed answers. But for me and many other endometriosis sufferers, that’s not really the case. The constant pain takes a significant impact on not just my physical health, but also my mental health.

A study in the Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynaecology suggests that the medical treatment for the pain may not be sufficient and psychological interventions should also be recommended – hormone fluctuation can also impact mental health. Just months after my diagnosis, I found myself asking my GP to increase the dosage of my antidepressant and later once again. When I find my body breaking down, I also find myself having a mental breakdown. It’s frustrating to know that there is no clear end in sight. “It’s not fair,” I regularly cry to mum as she hands me my third hot water bottle refill of the day.

Constantly having to cancel plans last minute means that the friends who don’t understand what I’m going through view me as unreliable and flaky, and as a result slowly cut me out of their lives. Instead of spending the best years of my life going on nights out and making memories, I’m often at home in a puddle of tears as my inflamed ovaries take over my body and my life.

“The stigma and awkwardness around anything related to menstruation in South Asian communities, meant that many have had to suffer in silence”

Through my own diagnosis journey and by creating a dialogue in my wider family, I began to understand that endometriosis was something other relatives had also experienced. But the stigma and awkwardness around anything related to menstruation in South Asian communities, meant that many have had to suffer in silence. It was only when they were older and had children, that they managed to find some relief through the form of a hysterectomy.

Endometriosis affects one in 10 women, yet it’s one of the most under-researched chronic illnesses. There are countless organisations and advocates fighting for sufferers, but at times, it feels like our voices are going unheard. The Gender Pain Gap has found that women’s pain has been dismissed for centuries and is a result of deeply rooted institutionalised misogyny in the medical field.

The history of sexism in healthcare is complex. Symptoms like menstrual pain or depression used to be linked to witchcraft and hysteria, and these beliefs can still be common in rural parts of South Asia. In fact, up until the 1800s, doctors in Europe believed the womb wanders around the body in a sensation called ‘the wandering womb.’ Also, a recent government enquiry into endometriosis found that it takes an average of seven and a half years to receive a diagnosis. Perhaps by creating a dialogue surrounding abnormal period-related symptoms, not just in SA communities but societally, we can begin to tackle this issue.

“Endometriosis affects one in 10 women, yet it’s one of the most under-researched chronic illnesses”

My endometriosis journey has shaped my life in more ways than I ever considered possible. It led me to begin a masters in public health, where I was able to really focus on expanding research in the field and will hopefully continue to do in future years. My struggle has allowed me to find my inner-strength and reconsider my priorities. But it’s been bittersweet, if it wasn’t for my own battle, I most likely wouldn’t have met so many incredible people with the same condition or been influenced to advocate for fellow sufferers.

There’s still a long way to go. But if anything, if there’s one thing I really want; it’s for people to understand that living with endometriosis isn’t easy. I can only hope that we can begin to raise awareness on this debilitating and common condition, and eventually, lead to change.