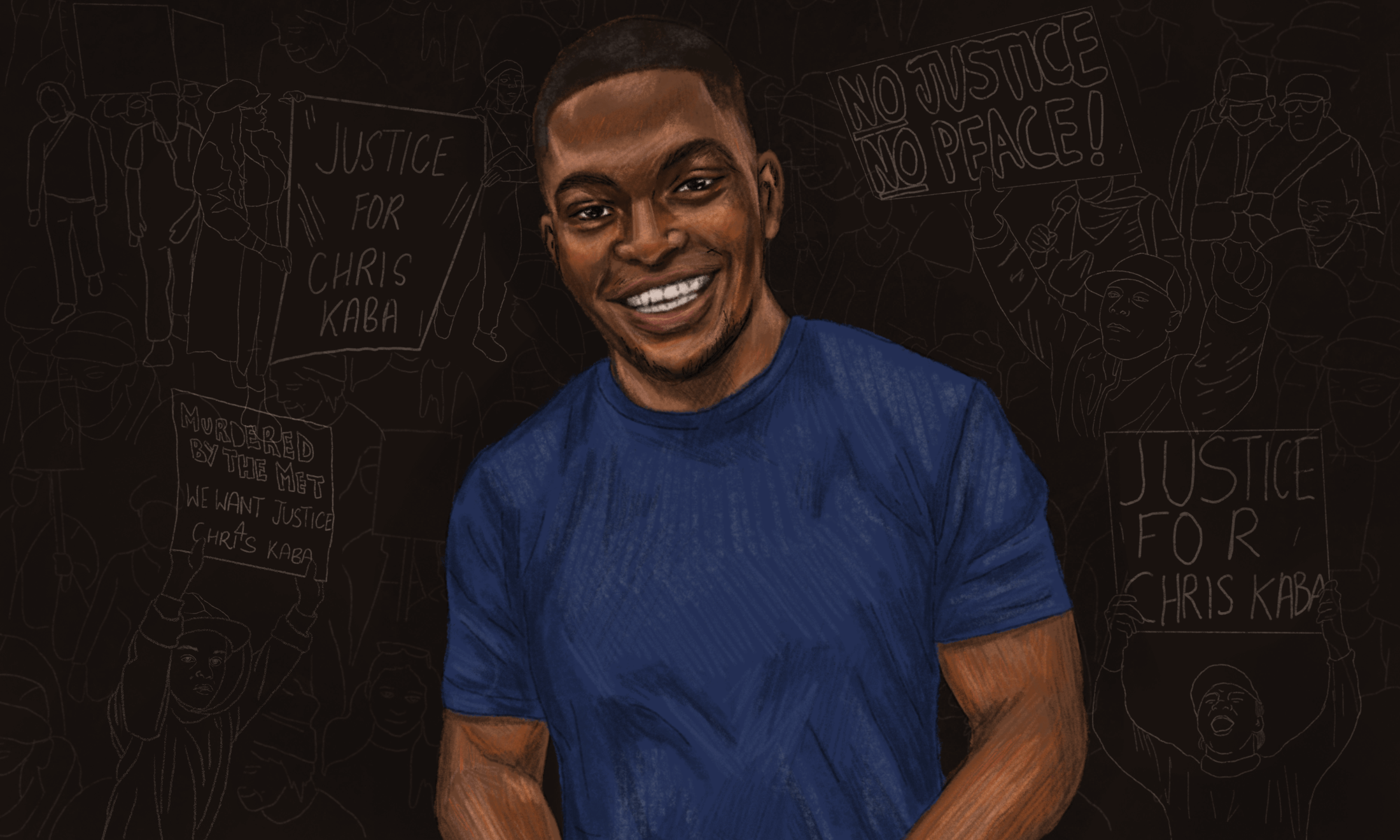

Photography by Elainea Emmott

What does black British activism look like in 2020?

With claims that the UK’s issues with racism are not as urgent as those across the pond, Seun Matiluko interviews black British protestors, organisers and the families of those affected by state violence to find out the true picture.

Oluwaseun Matiluko

06 Jun 2020

When Emily Maitlis told George the Poet on BBC Newsnight this week that the country’s racial struggles aren’t “on the same footing” as struggles in the US, she probably didn’t realise that she was helping to eradicate the reality of decades of ongoing, systemic racism and the work of black activists in the UK to counter it. From protestors in 1960s Bristol, who stood up against the “colour bar” which prevented black and Asian people from getting jobs, to the anti-racist demonstrations in the 1980s in response to widespread police discrimination and use of “sus” laws, black people in this country have been protesting against state violence for years, and for good reason.

In the past few days, we’ve been on the streets again, shouting Black Lives Matter.

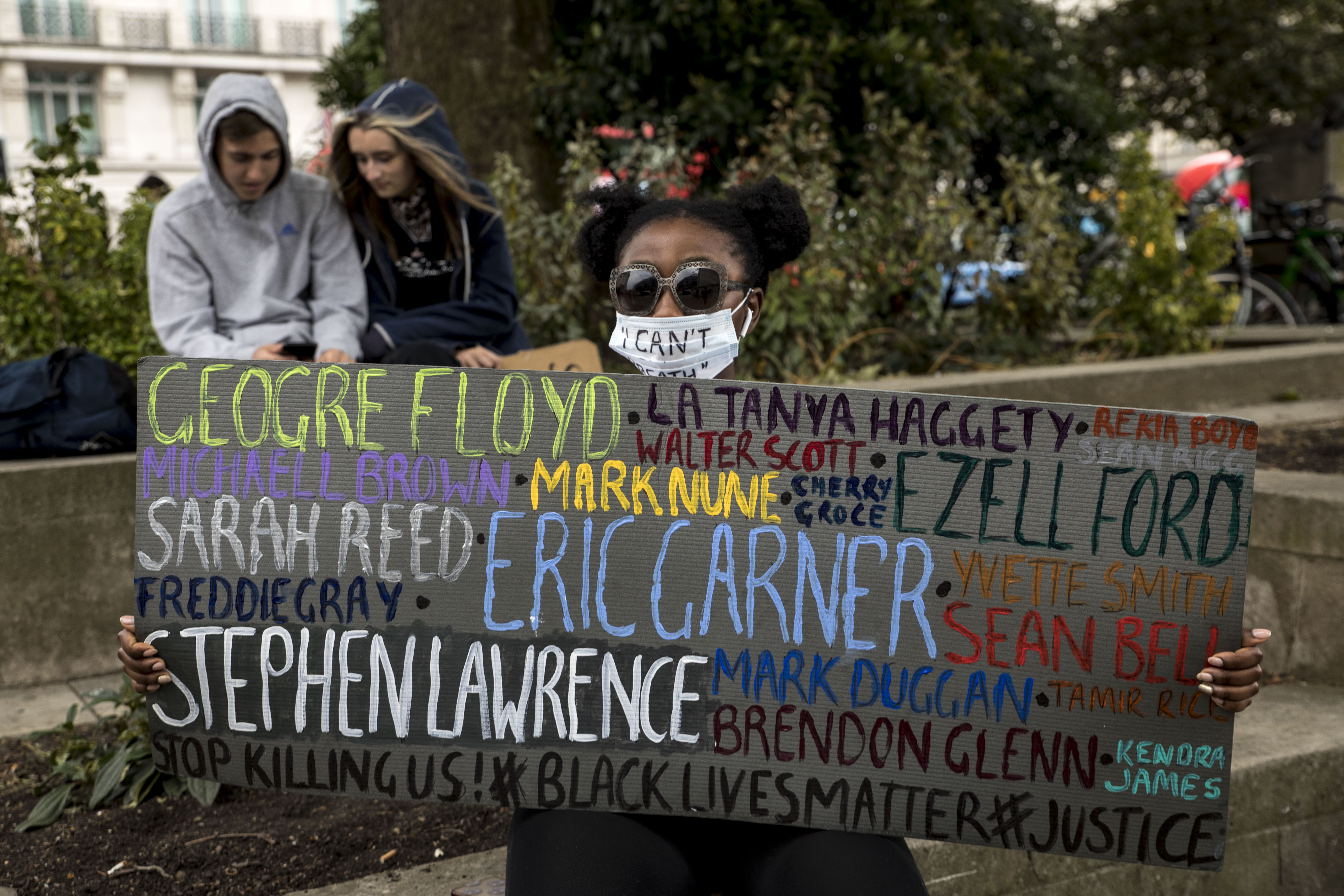

American actions

That the upsurge in black British activism is connected to deaths in America is important to discuss. Although it’s been suggested that “US culture wars are being imported” into the UK, many black British people feel genuinely connected to the consistent disregard for black life in America. They feel, in the words of NUS Black Students’ Officer Fope Olaleye, that “anti-blackness is global”. Expressing solidarity with those in America also means raising awareness about the killings of black British people by the state. Just as in France, where links have been made between George Floyd’s death and Adama Troaré, at many British protests you can see banners saying “The UK Is Not Innocent”, listing names like Sheku Bayoh, Sean Rigg and Joy Gardner.

“There are lots of ways that race plays out differently in Britain than it does in America. America is a far more lethal country generally”

Alex, a key member of Black Lives Matter UK (BLMUK), the most prominent BLM organisation in the UK (though independent of the US network), points out that many of those at the recent British protests have made impassioned pleas for justice for Belly Mujinga, the railway worker who was spat at by a man claiming to have Covid-19 and later died. The British Transport Police recently stated they wouldn’t be pursuing charges. Yvonne, a 20-year-old Bristol protest organiser, feels particularly strongly about Belly’s death. “I feel that the state doesn’t care enough about black lives,” she says. “When white people [have been spat at], they’ve prosecuted the person.”

But is it right to overtly connect American state violence to British state violence? Although there are some black people, like Monica Tolofari, a consultant midwife preparing to attend a Black Lives Matter protest in Leicester on 6 June, who believe that the African-American struggle is a “carbon copy” of the black British struggle as both are “fundamentally rooted in hatred”, academic and journalist Gary Younge emphasises that there are key dissimilarities. “There are lots of ways that race plays out differently in Britain than it does in America. America is a far more lethal country generally,” he says. For instance, in the US, black people were 24% of those killed by the police in 2019, despite being 13% of the population. The UK’s annual figures for deaths in police custody are not so grave, in part because most of our police do not carry guns.

State violence in the UK

Even so, as pointed out by Aadam Muuse, an organiser sporadically involved with BLMUK since 2016, “one life is one too many” and the UK’s statistics on state-involved killings are still worrying. According to the Independent Office for Police Conduct, 23 people were killed in police custody between 2017-18, of which six were black. Less specifically, INQUEST, a charity that provides expertise on state-related deaths, posits that 45 people died in police custody between 2017-18, of which 12 were BAME. They have also found that of the 1700 British people who have died police custody since 1990, 14% were BAME. All of these figures suggest disproportionality.

One of the first incidents that woke Aadam up to the issue of state violence against black people in Britain was the case of Smiley Culture, a black man and Reggae star who died in 2011 during a police raid. The circumstances around his death are controversial, as despite him being handcuffed, the police claim that he committed suicide by stabbing himself with a knife. As Aadam explains, “That was immediately suspicious to a lot of people.”

According to INQUEST executive director Deborah Coles, black people in the UK are often profiled by police officers as having “superhuman-strength”. This also came to light in the death of Joy Gardner, who deportation officers gagged and bound in 13 feet of tape, claiming they needed to do so because of her strength. The Met police have been found to use force against black people four times more than they do white people, and black people are three times more likely to be tasered. Related to this, in May a worrying video emerged of a black man being tasered in front of his screaming child in Manchester, with GMP facing accusations of using unnecessary force.

“Racism is a hardy virus that will adapt to the body politic that it’s in”

Another heart-breaking recent case of state violence in the UK is the killing of Olaseni Lewis. Seni, who was 23, voluntarily admitted himself to Bethlem Royal Hospital after suffering some mental health difficulties in 2010. Days after his admission medical staff contacted the police, claiming that Seni had become agitated. He was held down by 11 different police officers and his brain became starved of oxygen, killing him. An inquest found that “unnecessary, unreasonable and excessive force” was used on Seni, yet many of the officers involved were cleared of gross misconduct. Seni’s parents were able to get legislation put through in 2018 which now puts strict regulations on the use of force in mental health units.

Reflecting on Seni’s law Ajibola Lewis, his mother, hopes it will help other people. “It’s a small step but I know it’s an achievement,” she says. Another devastating case of state asphyxiation can be found in the killing of Jimmy Mubenga on a deportation flight to Angola in 2010. He was restrained, face-forward, by G4S officers and much like George Floyd, some of his last words were “I can’t breathe”.

However, racial inequality in our criminal justice system does not just affect adults. The 2017 review conducted into the criminal justice system by David Lammy showed that black people are more disproportionately imprisoned in the UK than in the United States and that the number of BAME people in youth prisons going up from 25% to 41% in the past decade. INQUEST’s Deborah Coles reminds me of the death of Gareth Myatt, a 15-year-old mixed-race boy in a secure training centre run by G4S, who became the “first child to die” by being “restrained to death”. 5ft 5 and 6 ½ stone, Gareth apparently raised his fist at the two adult male and one female officers who pushed him into his bed for up to seven minutes until he died from asphyxiation in 2004. A jury ruled his death accidental.

Bella Sankey, director of Detention Action, an organisation which supports people held in detention centres and campaigns for immigration reform, argues that more people need to connect the conversation on police brutality to other forms of state inequality. “The conversation on deportation and detention hasn’t been made mainstream enough,” she says. She goes on to say that while most people in Britain were outraged about the Windrush scandal, many do not realise that the descendants of that generation who are here because their elders came over are now being deported back to countries they barely remember.

All of these cases and statistics are part of the reason why people like Gary Younge take issue with the notion that British racism is any “better” than American racism. “Racism is a hardy virus that will adapt to the body politic that it’s in,” he says. As put by Jesse Bernard, an assistant at Release, a charity for drug policy reform, tells me, “British racism is not more covert or less insidious, we see it every day in front of our eyes.”

Barrister Michael Etienne no longer questions whether institutions in the UK are racist. “[I question] why we don’t recognise the racism in the fabric of many of our institutions,” he says. “Black people are disproportionately stopped and searched, disproportionately subjected to excessive force and disproportionately likely to die in custody. In the criminal justice system: more likely to be prosecuted, more likely to receive longer sentences. Draw your own conclusions.”

UK protests

Photography by Natalie Mitchell

The disappointing thing is that although protests against state violence in the UK do occur un-linked to Black Lives Matter protests in the US, at the moment, the turnout is often low. No-one spoken to was really sure why, although some suggested that the disparity in media coverage of American state violence versus British state violence could explain it. As put by TAHLIAH, one of the organisers of an upcoming BLM Glasgow protest, “As a society, we are so easily consumed by what we see online-especially through Twitter and Facebook – the police brutality and the killings that happen in America are automatically on our screens because they’re spoken about so much.”

In 2016, not long after the global explosion of the Black Lives Matter movement, BLMUK and a number of other organisations organised a march following the death of Mzee Mohammed, an 18-year-old autistic black teen who died whilst being arrested by police in Liverpool in 2016. Outside of the organisers and Mohammed’s family, there were few others who showed up. “[It was] really small and there’s something that’s quite heart-breaking about that,” says BLMUK organiser Alex. Similarly, each year, The United Family and Friends Campaign, a coalition of those affected by deaths in police, prison and psychiatric custody, marches on Downing Street on the last Saturday of October every year. The marches tend to only draw in a small crowd.

Ajibola Lewis shares the sentiment that more activism needs to happen when instances of state brutality occur in the UK without similar high-profile instances in the US. “It’s good to shine a light on our problems here and we’re using this opportunity [the large-scale BLM protests] to do that, but of course I want it all the time,” she says. “If a light was shone on all the deaths maybe there wouldn’t be any more. The media doesn’t talk about it enough.”

“I don’t think it would have been as impactful if it hadn’t have started in the US, but it’s made people in the UK aware of how ingrained racism is in this society as well”

Numbers don’t seem to be our strength in the UK. Though we have many black British activist organisations in the UK, like The Black Dissidents, or The London Black Revolutionaries, they often have few nation-wide supporters. According to the 2011 census, black British people make up only 3% of the population. While figures may have increased marginally over the years, black British people do not have the large national community that African Americans have, and so, as Gary Younge argues, “[We’re talking about] a much smaller number, with far less resources.”

Nevertheless, we have seen in these past few weeks that people of all ethnic backgrounds in Britain are able to mobilise in their thousands in response to events happening in America. Everyone saw John Boyega’s impassioned speech at Hyde Park earlier this week, and the protests are ongoing. Two young black women, Tasha Johnson and Aima, have upcoming protests planned for 7 June under the #LDNBLM hashtag.

“It’s not going to stop until we see real reform and change,” says Tasha. “Sunday will let us know the grand scale of everything that’s going on. We can’t just do one protest. It has to be every day until we see real change. I think everybody feels it. This is the melting point of all these years of oppression and racism and classism and everyone is fighting back. I don’t think it would have been as impactful if it hadn’t have started in the US, but it’s made people in the UK aware of how ingrained racism is in this society as well. It’s really exciting, it’s really scary, but it’s the right thing to do.”

Elainea Emmott, a black photographer whose portraits and protest work covers black protests and representation, has been attending many IRL marches and protests because it is important to her to show support and use her creativity to raise awareness. “I felt like it was a moment in history, making a change and using protest to get our ignored voices heard,” she says of protests earlier in the week. “There were many nationalities supporting this rally but this was predominantly black people making a difference and showing support for our US brothers and sisters and the universal fight being black highlighting the racism that is here in the UK too.”

It seems that we feel ever-more connected to the African American community, as we continue to see episodes of anti-black violence on social media. However, although black British politics has often been global, we have not always consistently linked our struggles to those in America. As Gary Younge says, the 1980s demonstrations and the 2011 London riots happened without reference. But, it seems that at the moment, in order to keep up the momentum, tying events in Britain to those in America is what is needed. As Gary adds: “If these things are understood as solidarity, then we can use the attention that is being directed.”

Activism online

Photography by Elainea Emmott

Black activism in the UK is changing at speed because of the current pandemic. For many people, the bulk of their work is now taking place online. Though social media can often be jarring for black people, it’s also a huge space for change. For example, some YouTube creators like Funsho, inspired by Zoe Amira in America, are using their “Adsense” in creative ways, posting monetised videos with adverts running intermittently and assuring those who watch that all money generated will be donated to the Black Lives Matter movement.

Others, like The Black Curriculum, who traditionally do more work outside of the social media space, have been pushing actively for more support online; asking for donations through their Instagram to enable them to provide more black British history workshops for students in the coming weeks, and imploring their followers to write letters to the education secretary to campaign for the “lived experiences” of black people to be added to the history curricula. Separately, in the past week, a petition arguing for an updated GCSE reading list, including The Good Immigrant and Why I’m No longer Talking to White People About Race has reached over a quarter of a million signatures.

“We should be wary when efforts are made to marketise and commodify resistance movements”

While Alex acknowledges that the UKBLM Facebook page has been relatively inactive since the surge in support in 2016, she highlights that the group is constantly active on Twitter and will be posting resources for anti-racism on their page within the coming weeks.

Mireille, a mixed-race black British woman who works in publishing, recently went viral for posting a short and simple resource for “non-optical allyship” on Instagram that everyone from Sophie from Love Island to Ariana Grande shared. Whilst there are concerns that people will be reposting it to pretend that they care, Mireille is hopeful that at least some will read the post and “apply at least one step to their life”.

Of course, it’s not enough just to share posts, people must actively try and be “anti-racist” in order to make a change in our society. And as academic Remi Joseph-Salisbury argues, “We should be wary when efforts are made to marketise and commodify resistance movements.”

As Ajibola Lewis says: “If we get more people marching maybe things will change… If we sit back and don’t do anything, we get what we get.”

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?