Kamali is the heartwarming doc on India’s 10-year-old skateboarding protégé

It may have lost out on a BAFTA but this stunning film is a journey through defiant Indian girlhood, maternal bonds and those who dare to break society's moulds

Neelam Tailor

05 Feb 2020

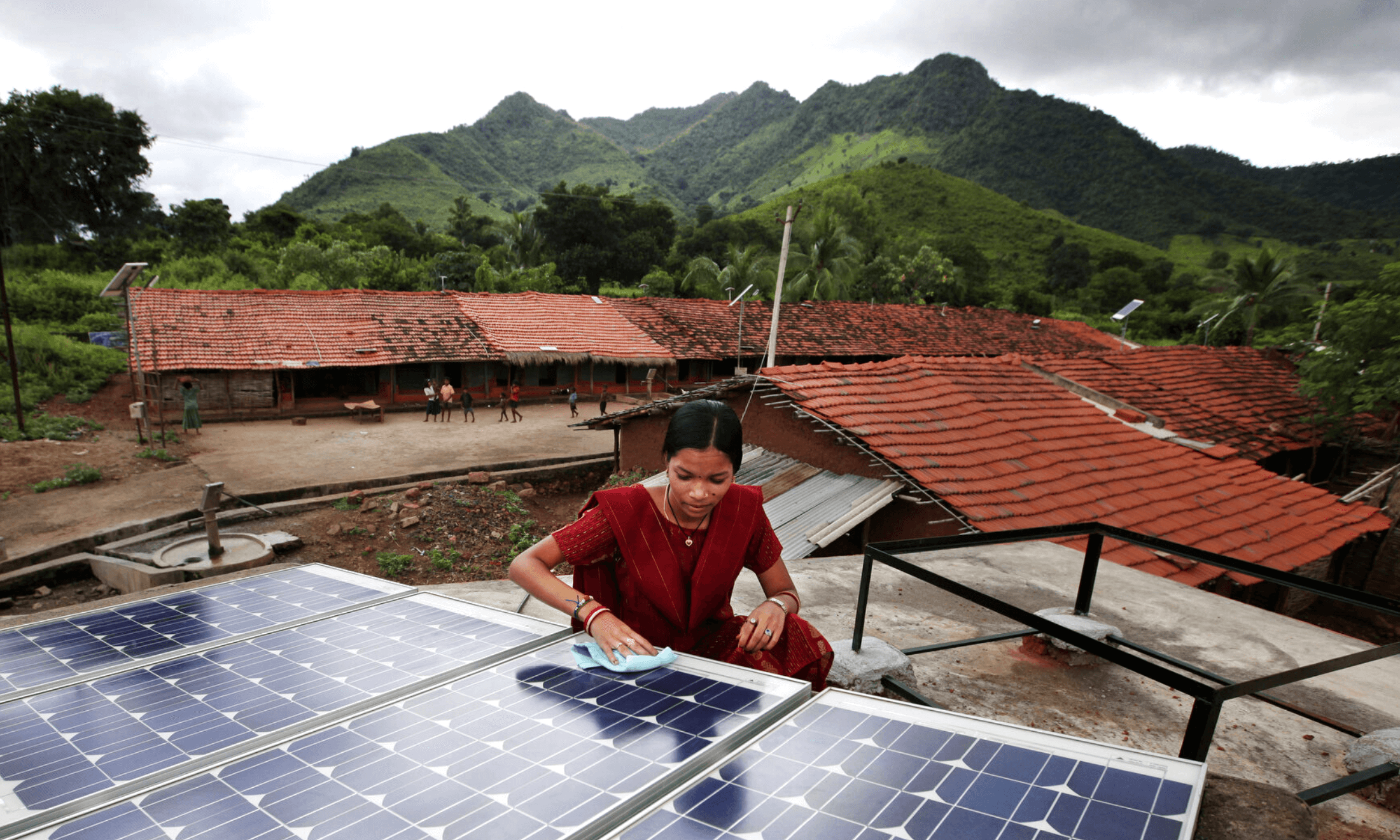

“Skateboarding!” 10-year-old Kamali says frankly, with a beaming grin, when asked what she had been doing that morning, and what she had planned for the rest of the day. Her godmother Aine had planned the Skype call, and took me to meet Kamali on her small skatepark in Mahabalipuram, India. Kamali took a second to greet me with her beaming warmth before asking if she could brush her hair before our chat. Aine gave me a glimpse of their beautiful fishing village in Tamil Nadu by the sea as Kamali skipped in the background, wearing a little cotton dress and bare feet.

I recognised the beach fishery, sandy skatepark and lazy palms from Kamali’s eponymous short-film, by Kiwi director Sasha Rainbow. The 24-minute documentary was shortlisted for this year’s BAFTAs, missing out to another film about skating girls – Learning to Skateboard in a Warzone (If You’re a Girl). Kamali also won Best Short Documentary at the Atlanta Film Festival and Raindance Film Festival. Sasha was filming a music video in Bangalore, India, centring on the stories of women skateboarders, when she first saw a photo of Kamali. Then just seven years old, she was the same height as her skateboard but was doing complex tricks in her sundress. It immediately sparked Rainbow’s attention.

Six-weeks of filming in the south Indian village opened Rainbow and her team’s eyes to the empowering story of three generations of women, Kamali, her mum Suganthi, and Suganthi’s mum, living together in the same house. Their unconventional story in a conventional village is told through their mundanities, soundtracked with modern electronic music, and cut with shots of Kamali’s private moments with herself drawing on walls that she’s not supposed to, or sticking her hair up in the bath with soap suds.

Kamali’s free spirit and self-assurance prompted me to wonder who raised her. How was she so liberated from the gender expectations that so-often shackle women in India? Suganthi divorced her abusive husband, giving Kamali and her younger brother Harish a better childhood than her own. “If my marriage had gone well, I would have kept Kamali locked away at home like I was,” Suganthi explains in the film. In 2017, India’s divorce rate was just 1%. Not because of endless marital bliss, but because of the harsh shame and stigma women are obliged to bow to. Divorce has been seen as a failure, often forcing women to stay in abusive relationships in an attempt to preserve the sanctity of marriage. An Indian census analysis showed that more women are divorced than men, exemplifying the gender bias that means divorced women are looked down on and struggle to remarry. There is a culture of putting familial reputation and duty before individual suffering. Suganthi’s courage and strength is even more inspiring within this context. Skateboarding is a vehicle to empowerment for her daughter, and she encourages her to break free of the mould that restricts so many Indian women. “My mum encourages me,” Kamali says. “She told me how to skate and she wants me to be happy.”

The film’s unwavering vibrance was rooted in Kamali’s uninhibited playfulness, something I felt in abundance during our chat. In the brief moments, the camera would move to Aine, it would pan back to Kamali upside down in a handstand, unable to contain her infectious vim. When there was a gap in conversation, Kamali would ask questions like “Do you have pets?” or “where do you live?”. I opened my curtains and showed Kamali my grey cul-de-sac of terrace houses. Aine remarked how cold and rainy it looked, asking Kamali “would you want to go there?”. Aine and I both expected a “no” but got a resounding yes. “I really want to go there,” she says, assessing the pavements as being perfect for skateboarding. It’s clear the hobby has become an obsession. “I feel like I’m flying in the air,” she adds before whispering and pressing her finger to her lips “I prefer it to tuition… shh”.

“My mum encourages me. She told me how to skate and she wants me to be happy”

Kamali

Kamali is so much more than a story about a girl and a skateboard. Speaking to gal-dem, Rainbow credited much of the film’s success to Suganthi. “The willingness of Suganthi to be vulnerable and honest was so brave.” She drew inspiration from Spike Lee’s Do The Right Thing, a film about racial confrontations on a block in New York City on the hottest day of summer, but their experiences in the village meant the focus shifted from the community onto Suganthi’s family. “We knew from having already met Suganthi that the village were opposed to her allowing Kamali to skate and that the family were fairly ostracised because Suganthi was a divorced woman,” she explains. Unsurprisingly once the cameras came the community was less hostile. “When we got there, people behaved as though they were very supportive. This sort of forced us to focus on the family more and in the end make a more intimate film about a mother empowering her daughter, and inadvertently empowering herself in the process.”

Throughout my conversation with Kamali, tales of her caring nature became a recurring focus. She cares for stray dogs in the area, proudly calling them her pets, even though her mum doesn’t like dogs and tells her not to. She welcomes outsiders, teaching them to skateboard. And when I tell Kamali about my fear of skateboards since I fell off one, she sits up and, with such a warm sincerity, offers to give me a skateboard and teach me. When asked what she wants to do in the future, she confidently says, “Be a kids doctor, or a dog doctor, or an animal doctor, or a doctor.”

As a white woman making a film about a socioeconomically disadvantaged brown girl, Rainbow was conscious of her privilege in the situation. In a 2012 poll of gender specialists around the world, India was voted the worst G20 country in which to be a woman. The gaze could easily turn exploitative. But in focussing on the close-knit dynamics through their own words, it’s a must-watch look at familial bonds. The team are also giving back, as they’re now trying to raise funds to build Kamali a bigger skatepark, and for driving lessons so Suganthi could become a taxi driver. It would be a life-changing career for her.

Since the film’s success, Suganthi told Rainbow that she used to be referred to as “her mother’s daughter”. Now, people call her “Kamali’s mother” – a massive show of respect. Other parents are now allowing their girls to skateboard, with Kamali at the helm teaching them. So what is the takeaway from the film? “Massive change starts with just one person,” according to Rainbow, while Kamali says she wants to “motivate girls to skateboard” all over the world. To me, the film is a beautiful reminder of how important it is to go against the grain.