Heedayah Lockman

After I was left to miscarry alone in A&E, it was my Tamil community that cared for me

While having a miscarriage was a painful and scary experience, the care and support I received from my mother and our community made me wish I’d reached out sooner.

Abinaya Nathan

19 Oct 2022

Content warning: This article contains mention of miscarriage.

The long wait at my local A&E while I was miscarrying may have been the worst six hours of my life. Since then I’ve declared more than once, only half-jokingly, that even if I was in a life-threatening situation, I would rather die than ever step foot in an A&E again. As the hours ticked by, both my masked breath and my mood became increasingly foul. I watched person after person who had arrived after me be called in. There were plenty of other patients coming in accompanied, but with blanket pandemic rules still in place and needing neither a carer or interpreter, I wasn’t deemed vulnerable enough to be one of them.

I’m not ignorant to the pressures of our health service, and I was by no means expecting a luxury stay. But I was not prepared for the feeling of hopelessness that came when I tried to advocate for myself, and when I tried to get answers to questions that I was made to feel stupid for asking. What happens during a miscarriage? Who was I going to see? What would happen when I was finally seen? I wish I had followed my instinct and gone home, because when I was finally seen after six hours, I was given paracetamol and told to wait for a phone call to get a scan in the coming days.

Thinking of those hours I spent circling the packed waiting area still fills me with a hot surge of rage and humiliation. I was unable to sit for more than five minutes at a time because of cramps, and snapped at by security for wanting to hold my partner’s hands in the doorway for a few seconds.

“The lack of understanding and concern I received from the NHS was unacceptable, and reflects a health service that is wholly underfunded and unsupported by the government”

At the time, I didn’t know anyone else who had gone through a miscarriage. The resources available online, like the NHS website, told me next to nothing. While I was waiting, I found a few tabloid stories about pregnant people left to bleed and cramp for hours in A&E just like I had. I didn’t have the energy to dig further. I had spent the first eleven weeks of my pregnancy hiding from my family and friends, and, as the night of the miscarriage compounded my loneliness, I began wondering why I had cut them out of this part of my life.

My partner and I had decided to keep the pregnancy a secret, including from our families, until the end of the first trimester as I had a large fibroid which I was certain would make a healthy pregnancy unlikely. I was also diagnosed with gestational diabetes from my first blood test with a midwife. Changing my diet drastically was hell, and I was ridden with guilt about overindulging in the months before I became pregnant. I cried every time I had to inject myself with insulin. The medication gave me horrible indigestion and made me sleepy throughout the day, and barely able to work. I lost the weight I needed to, but I was miserable. I couldn’t imagine surviving seven more months of this.

“While our relationship in my adulthood has often been strained, I felt ashamed for underestimating my mother’s ability to care for me”

During the six weeks I knew I was pregnant, I spent every Tuesday at the maternity unit’s diabetic clinic. I eventually built up the nerve to speak to some of the other women there who were from my community. All the Tamil women I met at the clinic had left the homeland as adults, either as asylum seekers or as the spouses of newly recognised refugees. Their parents and most of their natural support system were thousands of miles away in Northern Sri Lanka.

We mostly spoke about how difficult it was to keep our blood sugar levels stable without feeling utterly miserable. During a conversation with one of the women, she recommended I ask my mother for some traditional Tamil health food: red rice, fish curry with sarakku thool, Indian pennywort or moringa.

On the second day that I was miscarrying after my A&E visit, I gave in and called my mother. I was overcome with a craving for hot red rice kanji, creamy and bland, with just a bit of jaggery for sweetness. My mother was upset that I had left her out of the loop until that point, but she managed to keep her impulse to scold in check.

When she came over, she brought with her mild curries with extra ginger and turmeric. She made me spicy Ceylon coffee with egg and sugar whipped in. She showed me how to slice bits of aloe vera to place on my forehead when I was feeling hot and bothered. While our relationship in my adulthood has often been strained, I felt ashamed for underestimating my mother’s ability to care for me.

“Loss was spoken about in whispers, as a child I understood this as a manifestation of grief, and not as stigma”

The neglect and stigmatisation of women’s health and wellbeing in South Asian cultures is a stereotype that receives traction both in the mainstream media and among second-generation young adults, but my own experience reflects a different story. In Tamil culture, a girl’s first menstruation is celebrated. The rituals may have roots in a patriarchal urge to reveal a woman’s fertility and readiness for marriage, but to me it illustrated a willingness to openly talk about menstruation.

These rituals involve family visiting and bringing traditional foods and items believed to bring health benefits to women. While the rituals are focused around women, male relatives are not excluded from participating or visiting. This suggests to me a regional counter-culture among my Eelam Tamil community, since in mainstream Hinduism, menstruating bodies are deemed to be polluting and require a form of quarantine. Unfortunately, a trend towards increasingly ostentatious puberty ceremonies in diaspora Tamil communities while periods remain a taboo topic in society at large, has meant that this celebration remains divisive for many, particularly among second-generation diaspora Tamils.

During my adolescence and young adulthood, I experienced extremely painful cramps, migraines and vomiting during my period. My father and brothers never hesitated to help, running to the shops to buy me pads and brandy to mix into my coffee, or to take me home if I was sick at school or during a family function. Similarly, I have never had any shortage of support and care, both from my aunts and uncles, while visiting on holiday, either in the homeland or in other diaspora countries.

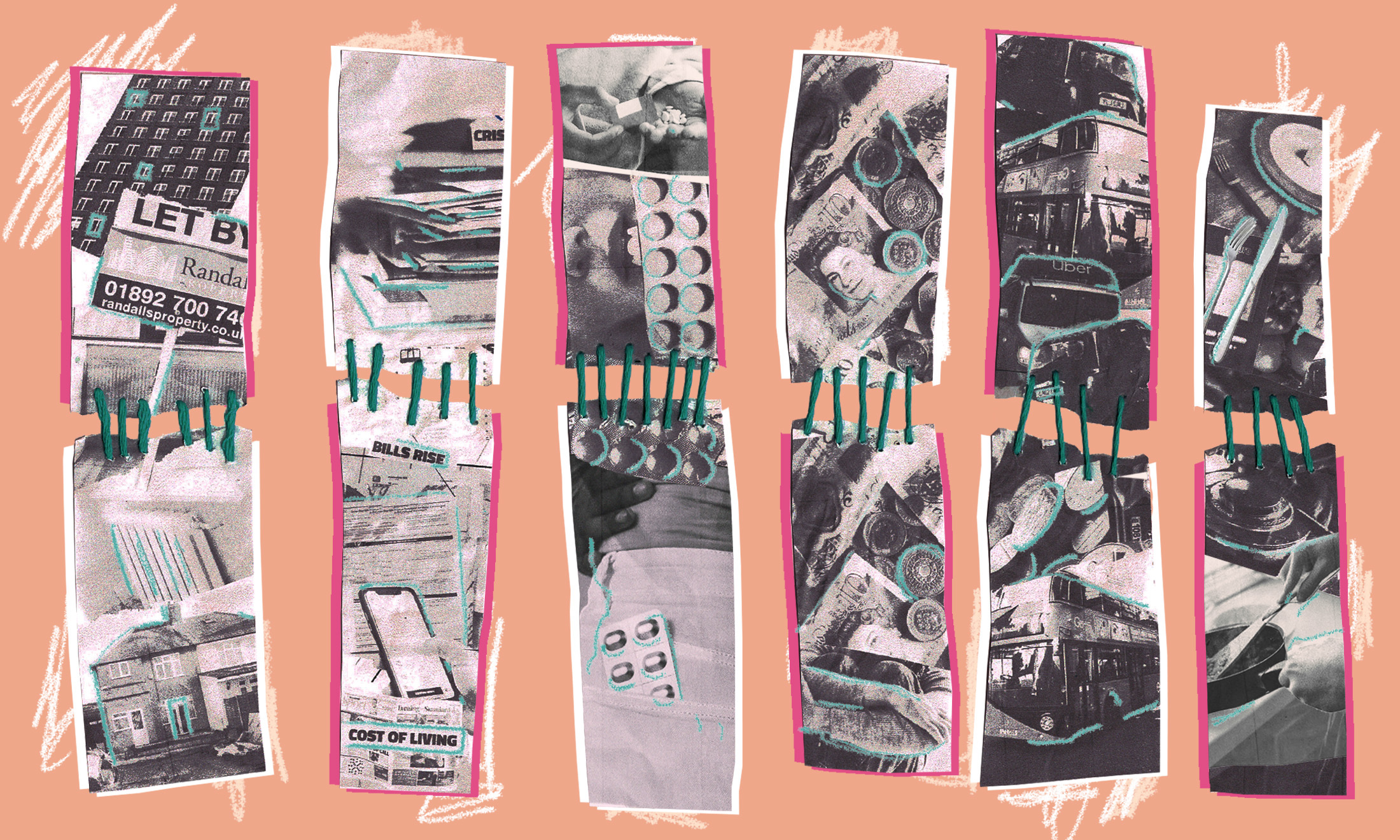

Although I often hear that miscarriage is a taboo topic among Tamil and South Asian people in general, I remember as a child visiting several aunts who had miscarried, with other relatives gathering at their homes to cook and keep them company. Although the loss was spoken about in whispers, as a child I understood this as a manifestation of grief, and not as stigma. While my community’s emphasis on women’s health could be attributed to a cultural obsession with preserving fertility, I am still grateful for it, especially living in the UK, where pregnant people can feel economic pressure to work until the day they give birth, gynaecology is woefully underfunded and anything short of cancer is classed as non-urgent.

“While having a miscarriage was a painful, isolating and scary experience, feeling connected to my mother and community carried me through it”

Where the hospital decided that I did not need care, my mother stepped in. The knowledge she was able to tap into was something she inherited through generations of tradition, from the care she herself received as a new mother in Jaffna, and from helping her sisters, aunts and cousins in her youth. While having a miscarriage was a painful, isolating and scary experience, feeling connected to my mother and community carried me through it, from gentle scolding to hot curry.

The lack of understanding and concern I received from the NHS was unacceptable, and reflects a health service that is wholly underfunded and unsupported by the government. What I learned that night, miscarrying by myself in A&E, is that pregnancy and pregnancy loss are not things that should ever be experienced alone if you can help it. Instead, these pivotal moments, that many of us will experience, should be times when we gather together as a community, to offer our support, love and care.

The contribution of our members is crucial. Their support enables us to be proudly independent, challenge the whitewashed media landscape and most importantly, platform the work of marginalised communities. To continue this mission, we need to grow gal-dem to 6,000 members – and we can only do this with your support.

As a member you will enjoy exclusive access to our gal-dem Discord channel and Culture Club, live chats with our editors, skill shares, discounts, events, newsletters and more! Support our community and become a member today from as little as £4.99 a month.