Priyamvada Gopal’s new book documents our ancestors as agents against slavery and empire

Vanesha Singh

22 Jul 2019

National conversations on empire are often framed within the confines of whether Britain should feel guilt for its evils or take pride in having “civilised the colonies”. This is known as the “balance sheet approach”, encouraging us to weigh up costs and benefits in order to make a neat calculation. It is a dogmatic, binary analysis of empire which stifles discussion and highlights the huge disparity between how much is known in academia, and what has yet to percolate into general British consciousness.

For Cambridge academic Priyamvada Gopal, there are bigger, more complex narratives worth advancing, and more constructive ways to approach Britain’s colonial past in order to unite a divided country around a common cause. That narrative is the story of antislavery and anti-empire.

Six years in the making, her new book, Insurgent Empire: Anticolonialism and the Making of British Dissent, explores the narratives of the rebels, intellectuals and parliamentarians that protested against British rule. She turns the spotlight on black and Asian activists such as Shapurji Saklatvala, C.L.R. James, George Padmore and several more, many of whom are “superstars” in the academic world and former colonies, but have been rendered to the margins of British history.

“Priyamvada’s book demonstrates that freedom was something Britain’s enslaved and colonial subjects demanded and fought for”

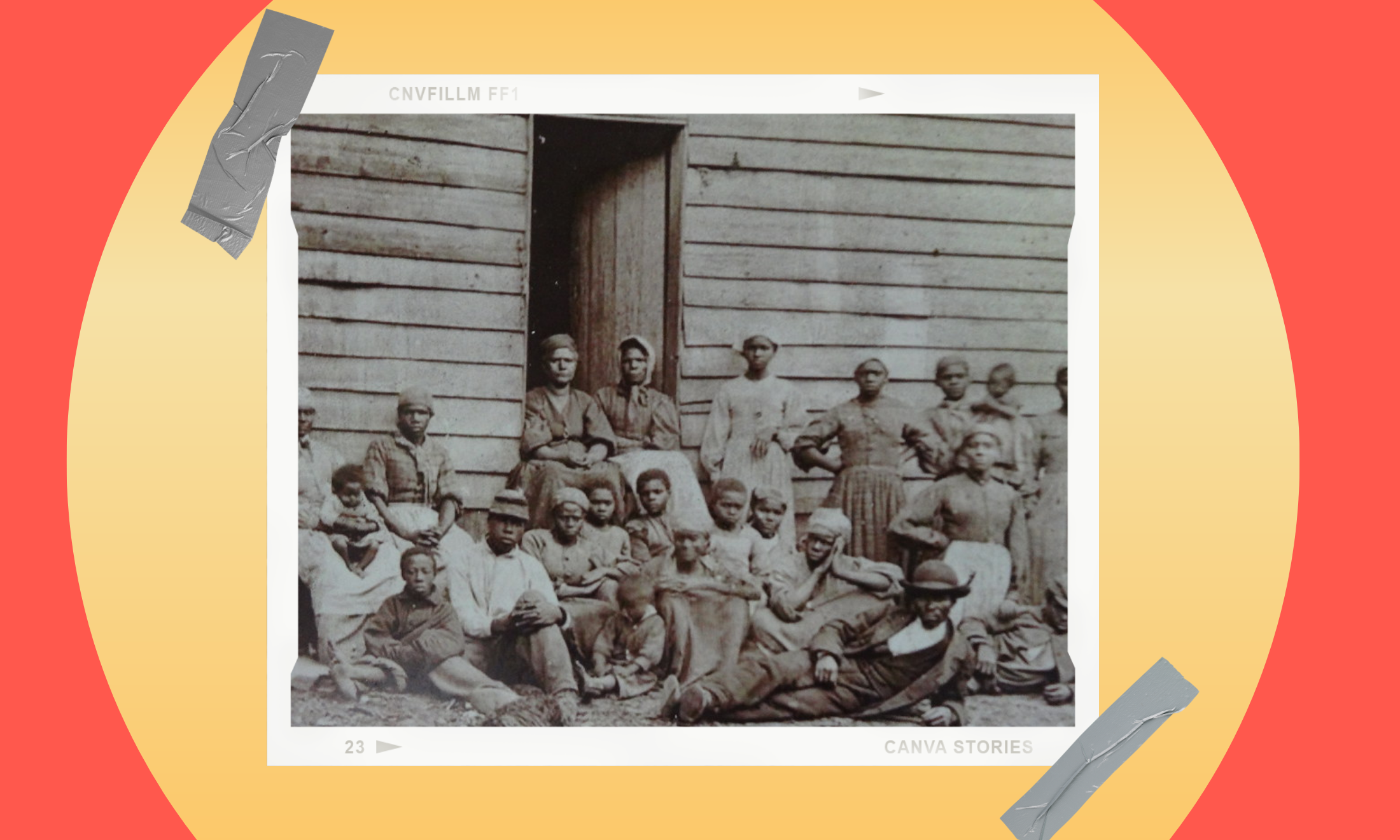

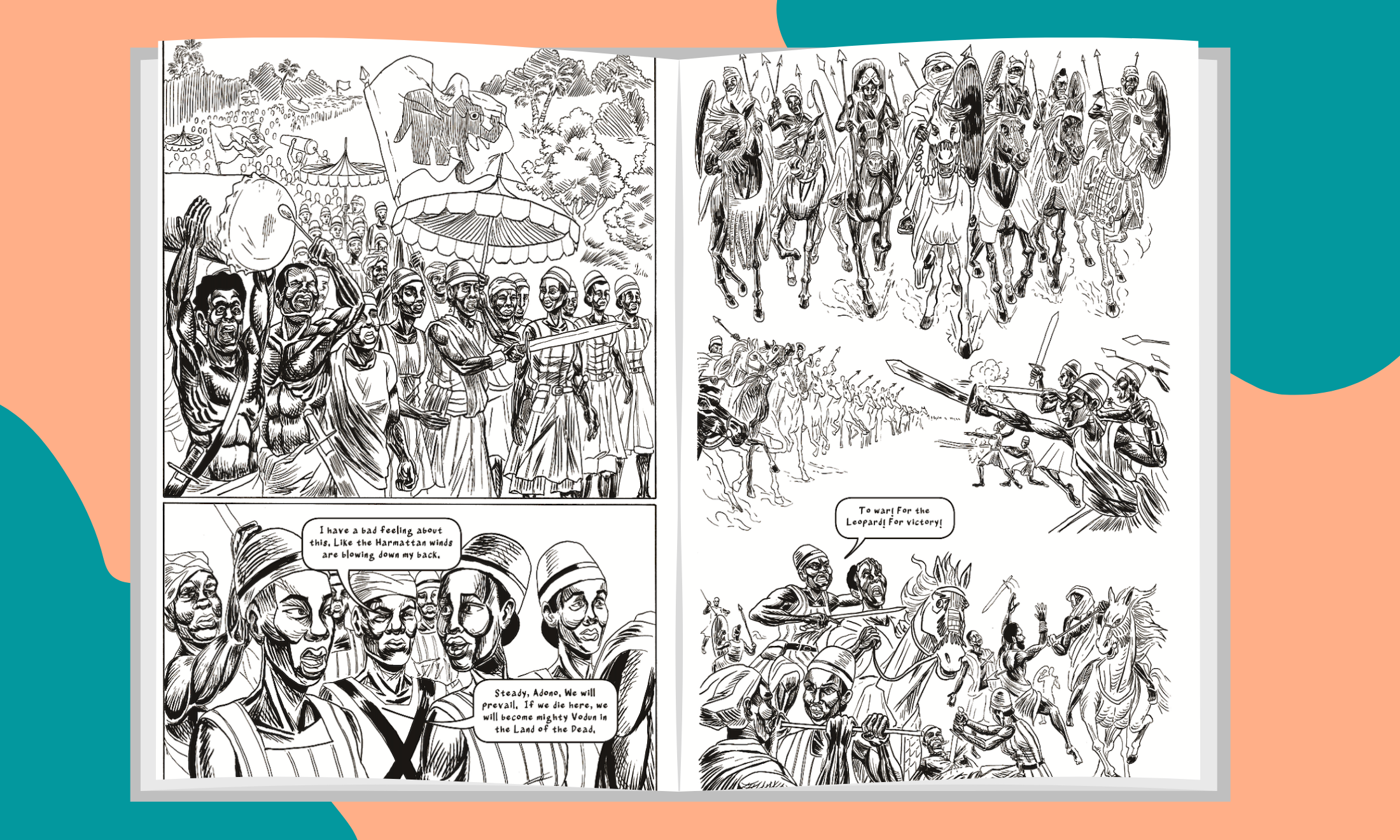

If myth-busting is the aim, then Priyamvada sets the record straight on several fronts. Her book demonstrates that freedom was something Britain’s enslaved and colonial subjects across Egypt, East Africa, the Caribbean and India demanded and fought for. “It is important for us to understand that we are not just victims,” she says. Instead, we see our ancestors as active agents in their own liberation. “This book is about recovering agency,” she tells me.

Insurgent Empire goes beyond simply recovering agency by recognising that resistance and rebellion in the colonial peripheries influenced white people’s criticism of empire in England. The power of her book lies in its reminder that people of colour have been crucial to the construction and prosperity of Britain, not just through their labour, but with “their values, their ideas, their resistance,” she says. We can gain a lot from reflecting on this: the far right’s attempts to make people of colour in the UK feel unwelcome or inferior is fundamentally undermined by the fact that we materially, ideologically and morally made Britain the place it is today.

Priyamvada’s approach breaks significantly from conventional wisdom which holds simply that the British granted freedom to their colonies. This is a false narrative which has been pushed by pro-imperial voices and plays into a white supremacist agenda by painting Britain – the motherland – as a generous nation “that always gives and never takes”. Priyamvada believes the narrative that Britain is always being “taken advantage of” is also peddled by the British mainstream media in the discourse around Brexit, asylum seekers and immigrants.

The most provocative aspects of her book are the instances where she recounts how Asian and black anti-colonial figures have collaborated and forged alliances with white British critics of empire. “White English people have been lied to and told that their ancestors were all pro-empire,” Priyamvada says. What Insurgent Empire reveals is that the bloodshed and ferocious repression enforced by the British as a response to protest in the colonies galvanised a “not in my name” movement back home.

This focus on solidarity between different communities is a refreshing way of looking back at a wretched part of history, and could also bear lessons for today’s activists. Her advice, to “make the allies you need to make, and through numbers, make it difficult to get ignored”, is a wise lesson for organisers of colour battling to be heard in the present day.

Priyamvada’s book has transformative potential not just for people of colour but for white Britons too. “British people of English ancestry and people of colour can call on a different set of traditions that united them,” she explains. “It’s not all ‘your ancestors oppressed me’, but that ‘my ancestors and your ancestors collaborated on the project of resistance’”.

“It’s not all ‘your ancestors oppressed me’, but that ‘my ancestors and your ancestors collaborated on the project of resistance’”

One thing I did notice, however, when reading Insurgent Empire, is the relative absence of women of colour. It’s something Priyamvada is eager to open up about: “This is my great regret … and it’s important for me to mention in the context of gal-dem, that the archives I looked at didn’t yield these particular voices. But equally, I would hold myself accountable and say if I could do it again I would be more conscious about the archives and what they’ve left off”.

What comes through – time and again, even within just an hour of sitting down together – is Priyamvada’s ability to trust in herself but remain deeply self-critical. “What I want people to understand is that I can get it spectacularly wrong,” she says. Her honest reflection stems from her concerns about being awarded “prophetic status” on social media. Because let’s be honest: Priyamvada’s Twitter game is strong. Partly, this is because she refuses to mince her words – which is in fact a piece of wisdom she imparts to me. “We [women of colour] don’t need to tone ourselves down”.

Being an outspoken woman of colour has its repercussions, and Priyamvada has been portrayed as aggressive and unreasonable in the media. She is of course acutely aware of this: “I think [the British media] see me as the ungrateful postcolonial who doesn’t know when to keep quiet. It’s very clearly a racialised and gendered depiction of me.” And yet, Priyamvada remains defiant – in part due to the strong, supportive community she has on social media – but also, on behalf of the growing numbers of women of colour now studying at Cambridge. Their presence has not only Priyamvada Gopal “great comfort” but – she feels – has added to her responsibility to call out racism, sexism and injustice when she sees it.

Speaking truth to power can be incredibly taxing. Priyamvada is symbolic of an even bigger fight: she works at Cambridge University; an institution, which, along with Oxford created, maintained and benefited from Britain’s colonial empire. As Insurgent Empire shows, change happened when our ancestors made themselves difficult. We are in solidarity with Priyamvada as she continues to ferment unease in an institution that has yet to get its head around diversity, let alone decolonising its own hallowed halls.