Photography via Hala Mohamed

After Richard Okorogheye’s death, we must stop making missing people a comparative sport

No-one benefits when the cases of missing people are flattened and reduced by false equivalences.

Charlie Brinkhurst Cuff

09 Apr 2021

Content warning: mentions of murder and assault

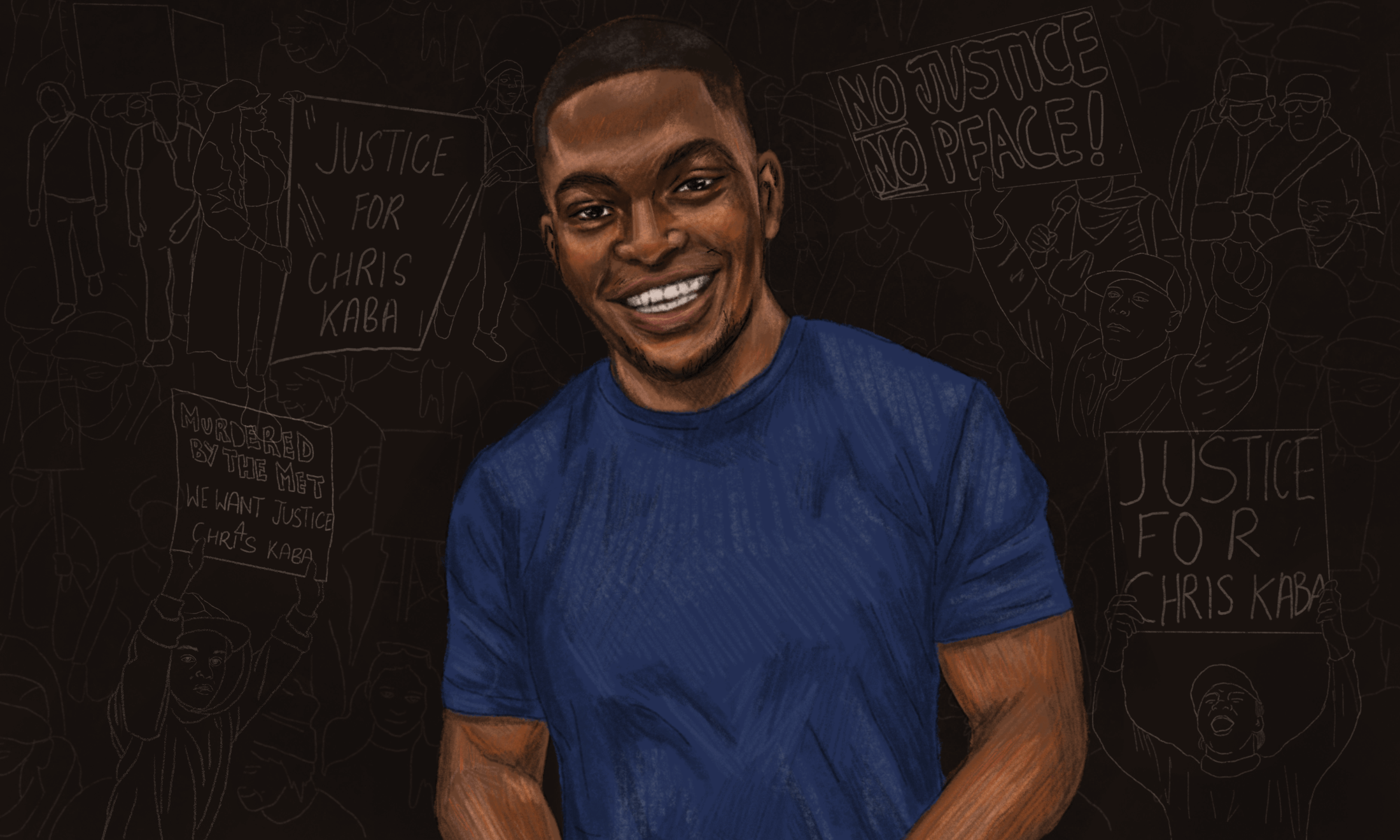

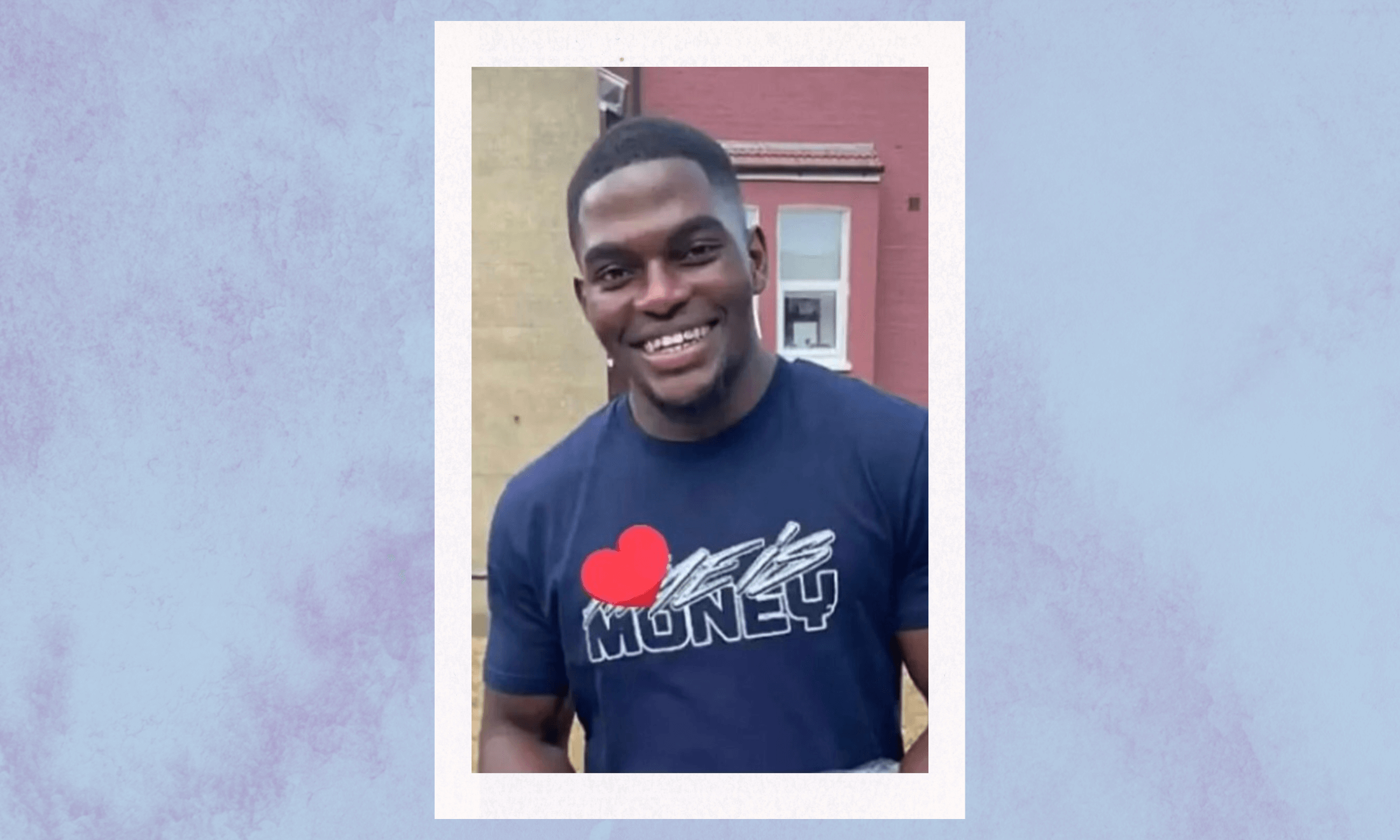

We’ll never know what might have happened in the case of Richard Okorogheye had the police not allegedly told his mother, “If you can’t find your son, how do you expect police officers to find your son for you?” and graded his disappearance on 22 March as “low-risk”. On Wednesday, Richard’s body was formally identified after being discovered in Epping Forest. He was 19 years old.

Richard was described by his mother as being her moon and her sun. The reason why she got up in the morning. In her words, he was intelligent, polite, and had a big, kind heart. He loved playing video games and owned a much-coveted Playstation 5. He was an only child. He was black. He was loved. His individual humanity must lie at the heart of every story told about him.

In the days since he went missing, Richard’s case has become a touchstone for ongoing discussions around protection and justice for vulnerable missing black people. Accompanied by an outpouring of grief and a demand for answers, his name has joined a tragic pantheon of black people failed by the boys in blue. But as the UK’s black community rallies in the face of this latest tragedy, we should take care not to promote false narratives surrounding missing people that do more to obscure the path to justice than ensure it.

Compare and contrast

From the moment Richard vanished into the London night, his case was met with comparisons to others. For better or for worse, social media has made missing people a sport of compare and contrast; quickly Richard’s name began to be mentioned alongside those of other black people who had been noticeably failed by the authorities in recent months. “If you care about [insert missing white person’s name here], you should be talking about [insert missing black person’s name here]”, was a familiar refrain, along with: “Why is no-one talking about [insert black person’s name here]?”

Often Richard’s picture appeared pitted against that of Sarah Everard, the 33-year-old marketing executive who was kidnapped and killed in March, or Madeleine McCann, the toddler who infamously vanished in Portugal over a decade ago. Everard’s case, in particular, felt like a poor comparison to make; she had vanished while walking home, her remains found hundreds of miles away. A serving police officer stands charged with the crime. Richard walked out of his house and was captured on CCTV heading into the Essex forest where his body was later discovered. Though this may change, at present, no other people are suspected of having any involvement in his death. The commonalities between Richard and Sarah are those of shared institutional police negligence. The differences in the circumstances of their disappearance are vast.

“Richard’s individual humanity must lie at the heart of every story told about him”

McCann’s disappearance also felt like a poor way to highlight the institutional dismissal of the plight of Richard’s family by police. She was a minor, who vanished while on holiday with her parents. Richard was an adult, living in the UK. This does not diminish the seriousness with which his disappearance should have been treated. But it raises uncomfortable questions regarding how we discuss and highlight the cases of marginalised people moving forward.

There is a notable and understandable resentment in the tone of comparative posts that demand to know why one person has been seemingly prioritised above another. I have been guilty of it myself. But rather than fighting over who gets a bigger share of the spotlight, we should be striving for equity. The public shouldn’t care less about cases such as Everard’s or McCann’s, they should simply care more about cases like Richard’s. And fundamentally, we shouldn’t need to use the cases of missing white women and girls to generate interest in the cases of missing black people.

In the long-term, these reductive equivalences might do more harm than good in raising awareness of black missing people. Each missing person’s case is unique and needs the same initial level of care and attention. But the speed of social media means false information is spread in the rush to pass it forward. Take the case of Keiran Campbell, a young black boy who went missing at the same time as Sarah Everard and was used as a direct comparison as evidence of police racism. Posts circulated containing inaccurate information about Keiran’s disappearance and continued to be shared long after he was found.

“The public shouldn’t care less about cases such as Sarah Everard’s, they should simply care more about cases like Richard’s”

What purpose does it serve our missing and murdered people to reduce their lives and deaths to a sloppy ‘gotcha’? Especially when we have such a horrifically large bank of existing proof to point to when it comes to police racism, without inventing details that can be used to trip us up later.

Yes, we need to pay particular attention to the cases of missing black people because the state and media aren’t necessarily doing so. But we also need to move towards a place of highlighting them without getting drawn into unnecessary equivalences, just because they’re shareable on social media. That’s not to say that comparison isn’t a useful tool when cases are directly in contrast – take the very different press and police response to the murders of Libby Squire and Joy Morgan. But they were comparable cases: two young women, abducted, sexually assaulted and murdered. Richard Okorogheye and Sarah Everard are not. In short, if comparison is the only power that we can use to get people to care, should we continue to utilise it? Quite possibly, yes. But with far more thought than is on show at the moment.

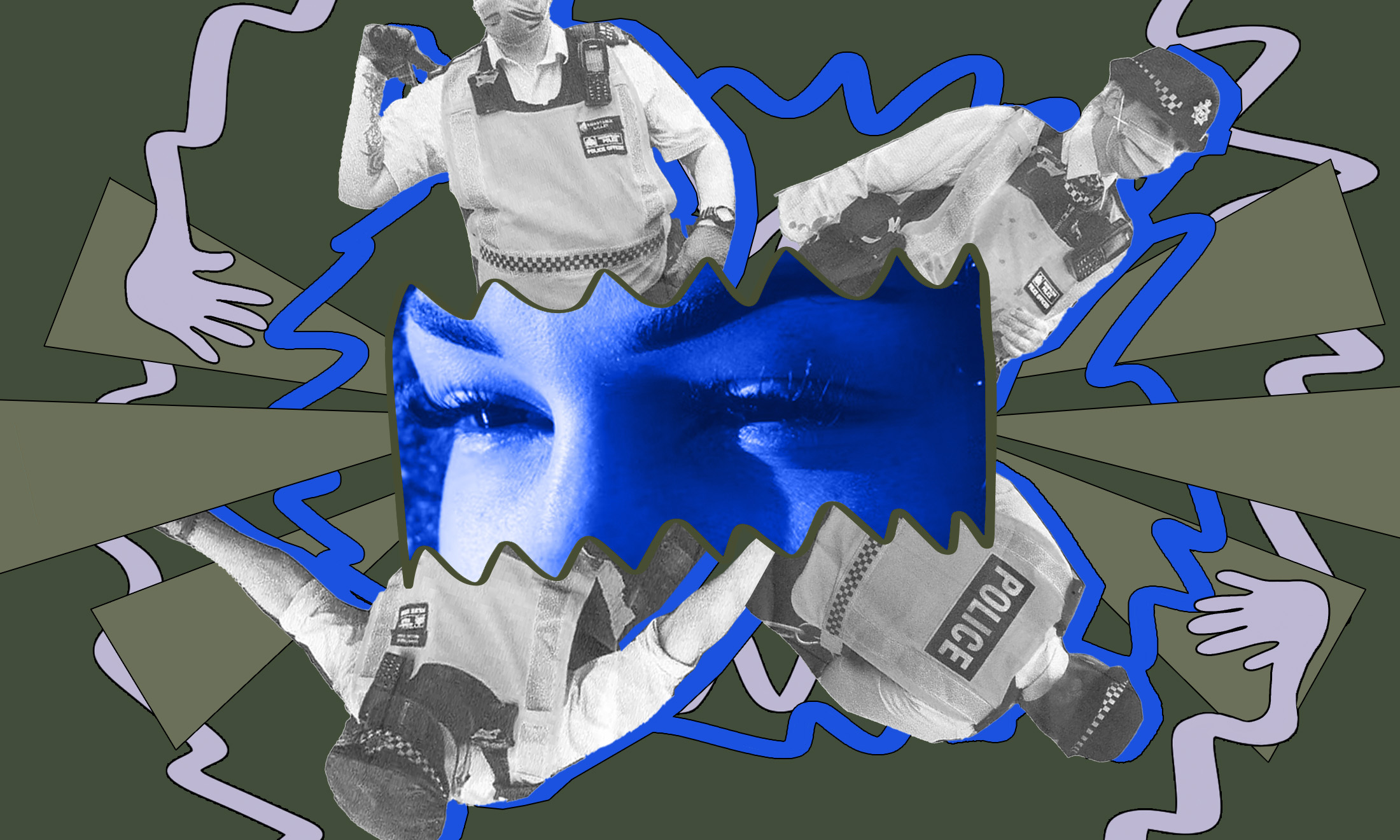

Spectre of racism

We know Richard was failed by the spectre of structural racism. He and his family have been let down by the Met Police. Like Joy Morgan, Bibaa Henry and Nicole Smallman, Blessing Olusegun and dozens of others before him, Richard’s death may not be directly due to police malpractice, but the harm for his loved ones left behind has been magnified tenfold thanks to their negligence. Evidence Joel Okorogheye joins a long list of black mothers like Aji Lewis, Myrna Simpson, Janet Brown and Doreen Lawrence forced to wear their pain publicly and traumatically to obtain justice for their children.

It is these women, the mothers of the missing, who are often left to bear the heavy burden of police racism. The police struggle to see black people as victims or think they could be truly vulnerable; we see that everywhere from sky high stop and search rates to the criminalisation of black men for as little as watching a YouTube video. It’s visible in police shootings of unarmed black men struggling with mental health issues, or stats that show black people are more likely to have force used on them by officers.

And yet, more than 20 years after the police were first judged “institutionally racist”, there seems little desire to address this on the part of the state, who wish to deny such structural prejudice exists altogether. In the face of this, it is understandable why false narratives surrounding vulnerable black people flourish. But sacrificing the truth for a lie is not going to further our cause, nor bring about the equality we seek.

“Sacrificing the truth for a lie is not going to further our cause, nor bring about the equality we seek”

As we round off this week, we know that Evidence Joel Okorogheye’s heart is broken. On Wednesday, she spoke about her loss to the Evening Standard. “We thought Richard would be found, or would just come home. But he’s not. My baby will never come home to his mummy again. He was taken away from me too early. The only child I have.”

Richard Okorogheye’s case won’t be the last of its kind. We should continue to use every tool in our arsenal to raise awareness and offer support to vulnerable missing black people if the state is not going to protect them as it should. But – while not taking scrutiny away from the Met Police who must continue to be held accountable for how they treat black British people – for Richard Okorogheye, for Blessing, for Nicole, for Bibaa, for everyone, we must respect the individual complexities of each missing person’s case and remember that regardless of any identity markers, first and foremost, they are human.

Britain’s policing was built on racism. Abolition is unavoidable

How Pakistan’s Khwaja Sira and transgender communities are fearing and fighting for their futures

Their anti-rape performance went viral globally. Now what?