Image via Annie Spratt/Unsplash

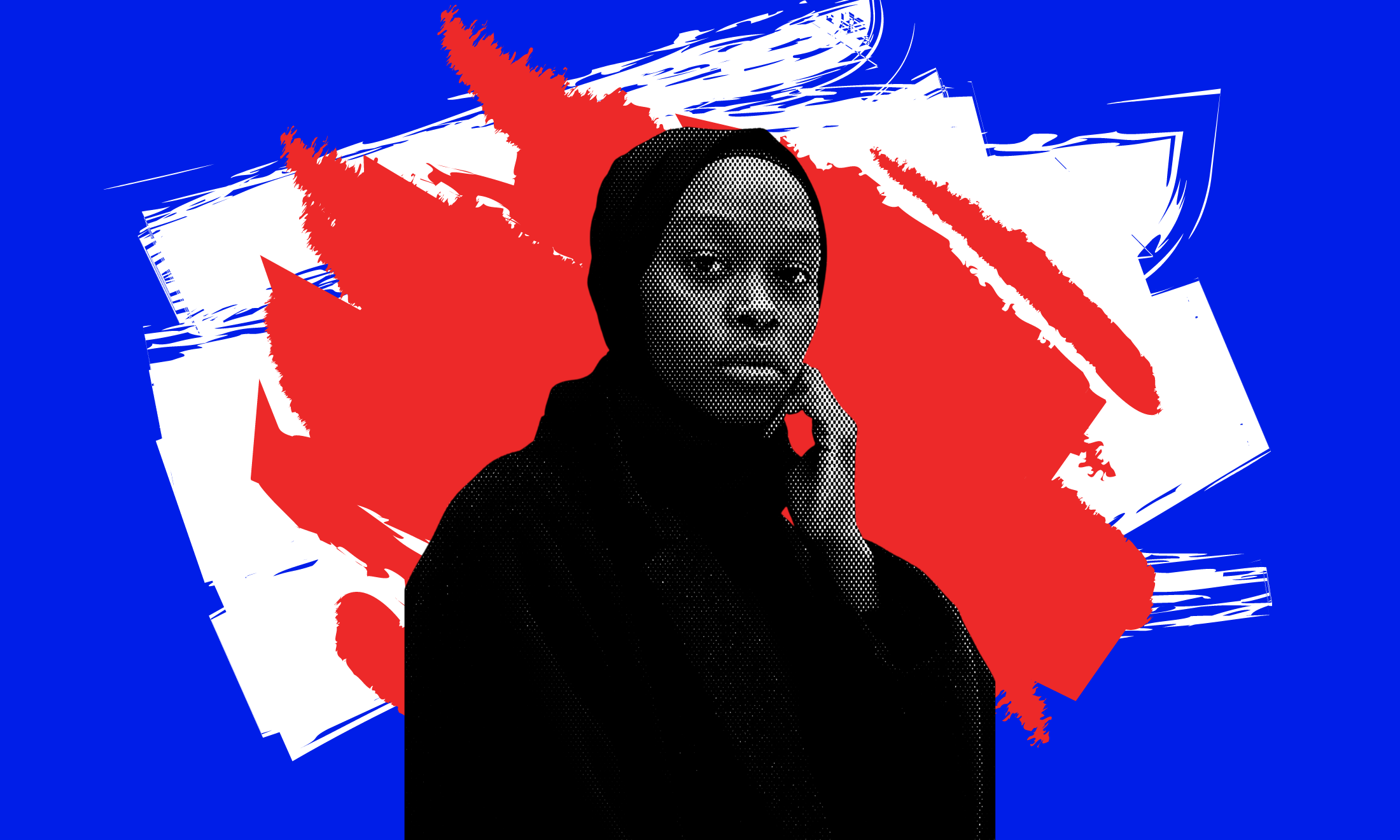

In a stunning twist of events, last month the Home Office took steps to revoke the citizenship of Shamima Begum just days after she called for a safe passage back to the United Kingdom. On February 19 a letter was delivered to her family residence stating an “order removing her British citizenship has subsequently been made”, rendering Shamima stateless. Despite reports to the contrary, her solicitor has confirmed that Shamima “has never had a Bangladeshi passport” making the UK’s move illegal under international law.

Shamima Begum was 15 years old when she was groomed online by ISIS fighters in 2015. She was one of a three girls who left their homes and schools in Bethnal Green, East London to go to Syria where she was married to a Dutch fighter in the Syrian city of Raqqa just ten days after arrival.

Now, four years on, The Times have discovered that Shamima Begum is living in a refugee camp in Syria, having left her partner and left ISIS. Two points in her interview with Times journalist Anthony Lloyd have captured the attention of the British public: the first being a perception that she hasn’t expressed regret about going to Syria, the second being her perceived normalisation of the violence in Syria. In an interview with The Times she states that seeing decapitated heads in bins happen “didn’t faze me at all”. Having experienced a child marriage at 15, and possibly having lost two children at only 19 years old, it seems reasonable that Shamima would be traumatised.

In response to assertions that Shamima displays lack of emotion in the interview, a family member explained “We like everyone else were utterly shocked by what we heard Shamima say in her interview with The Times. But to us, those are the words of a girl who was groomed at the age of 15; we are also mindful that Shamima is currently in a camp surrounded by IS sympathisers”. This context is crucial: Shamima was a vulnerable child when she left Bethnal Green, and is now a teenage woman whose every movement until recently has been controlled by her husband.

“UK Home Secretary Sajid Javid mocked Shamima, a survivor of grooming, for her comments that she was ‘just a housewife’”

Shamima later spoke to Sky News on February 16 where she said: “They don’t have any evidence against me doing anything dangerous. When I went to Syria I was just a housewife for the entire four years. Stayed at home took care of my kids.” Two days later, UK Home Secretary Sajid Javid stood in the House of Commons and mocked Shamima, a survivor of grooming, for her comments that she was “just a housewife” and vowed that to do “all he could” to stop her coming back into the United Kingdom.

Javid appeared pleased to explain that 100 people have already been stripped of their citizenship, prophesying the decision to revoke Begum’s citizenship that would be made the next day. This act will make Begum stateless, despite the fact that nationality is internationally recognised as a human right in the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD) 1969, the Human Rights Act 1998 and the UN Convention on the Rights of a Child (UNCRC) 1990.

The debate surrounding Shamima Begum’s case is now the centre stage for discussions on citizenship, human rights and how visibly racialised and visibly Muslim people are treated by the British state and the media. Race, class, faith, gender, colourism and distance to (or from) being born in the UK and having a British passport are key factors in how this debate plays out. Discussions largely boil down to an interrogation of who is and isn’t British, and the technique for tearing away Shamima’s “Britishness” is a relentless campaign of dehumanisation.

For example, The Mirror ran an article just two days before Shamima spoke to Sky News titled “Revealed: Shamina Begum’s middle-class terrorist husband who plotted atrocity in Europe”, illustrated with a photograph of Yago Riedijk prior to his conversion to Islam with a caption “Jihadhist Yago Riedijk is the husband of ISIS bride Shamima Begum”. The article describes Riedijk as “smiling shyly in a checked shirt”, and explains the he was “born into a ‘lovely’ middle class family” and was a “’polite’ little boy who would play football in the street in Arnhem”. In contrast, an article published by the Sun reads: “ISIS Bride Shamina Begum STRIPPED of British citizenship after showing no remorse for fleeing Syria”. The Mirror article insinuates that Riedijk was respectable before he converted to Islam: he’s not framed as an “ISIS groom”. In contrast, Shamima is not humanised through tidbits of information about her childhood, despite being a victim of online grooming.

“The British state has been making people stateless for quite some time to minimise a perceived threat to public security”

There is a growing sense that the revocation of Shamima’s citizenship sets a dangerous precedent for the arbitrary removal of rights. However, as Javid pointed out, the British state has been making people stateless for quite some time to minimise a perceived threat to public security. All people who are born to Bangladeshi parents are entitled to Bangladeshi citizenship and most of the Bangladeshi diaspora (known as “Bangladeshi origin foreign nationals” by the Bangladeshi High Commission) travel to Bangladesh without requiring a visa stamp. If this is what Javid meant by a new precedent, it looks at her identity as part of the Bangladeshi diaspora to travel without a visa and as an opportunity to obtain citizenship, albeit the website details that a ‘No Visa Required’ permit (NVR) is only valid within “the validity of the passport”. Shamima doesn’t have a passport, and therefore has no route to get to Bangladesh to use an NVR. Shamima’s passport will state that she is born in the United Kingdom, meaning that her ethnic background has been the sole link towards this enforced statelessness. We can only speculate whether the Home Office would treat a white Welsh person, for example, who went to Syria the same way.

Last November, the UK government was found to have unlawfully stripped British citizenship from two “alleged Islamists”. The government thought the two men, like Shamima, held dual heritage Bangladeshi-British citizenship but they actually only held British nationality. UKBA wrongly assessed their cases, and the UK were subsequently blocked from making them stateless. There are options for Shamima Begum to appeal the decision made by the Home Office to come home to Bethnal Green Green. Nonetheless, the revocation of her citizenship feels a million miles from “due process” and more like further intensification of immigration controls, in the name of “security”, fuelled by racism and Islamophobia.