from author

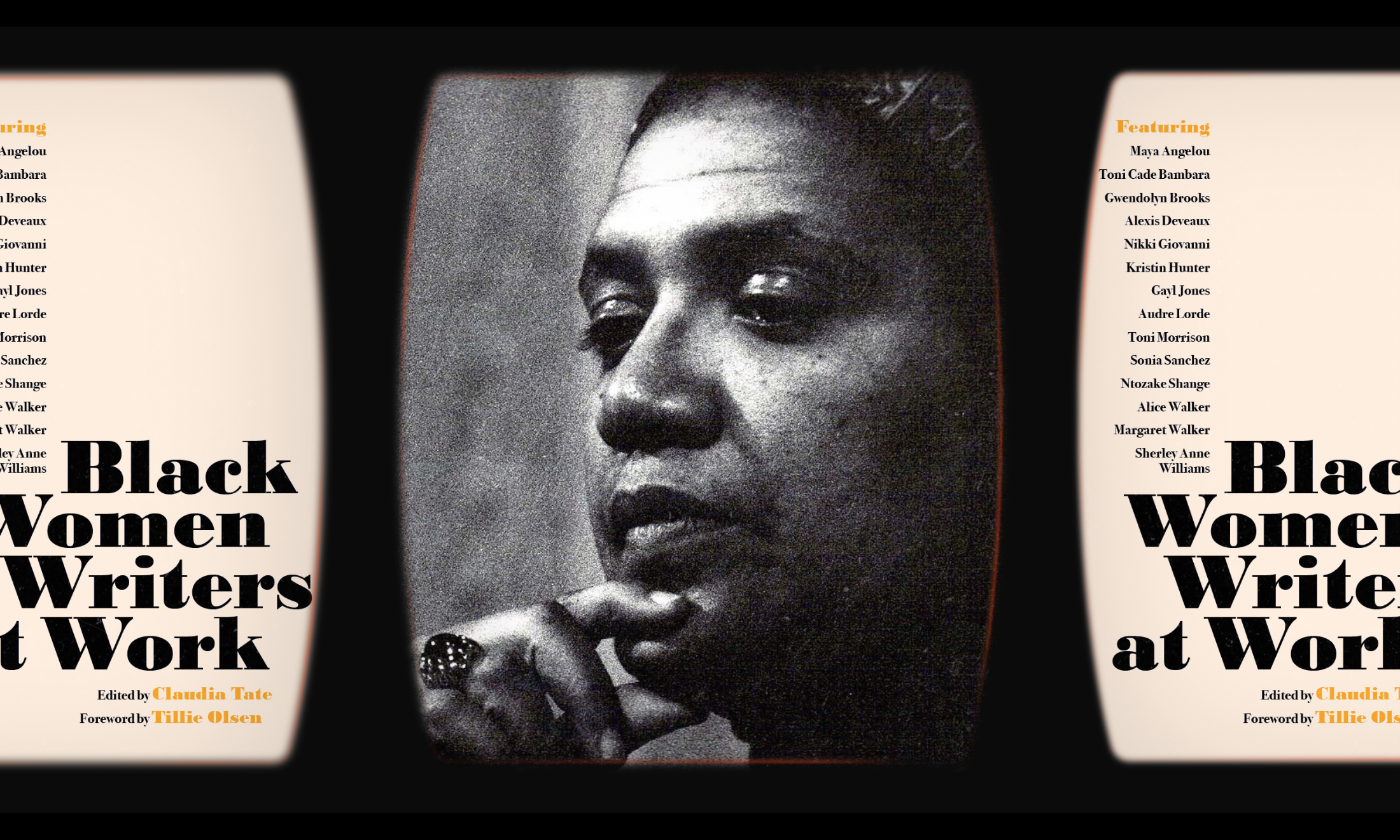

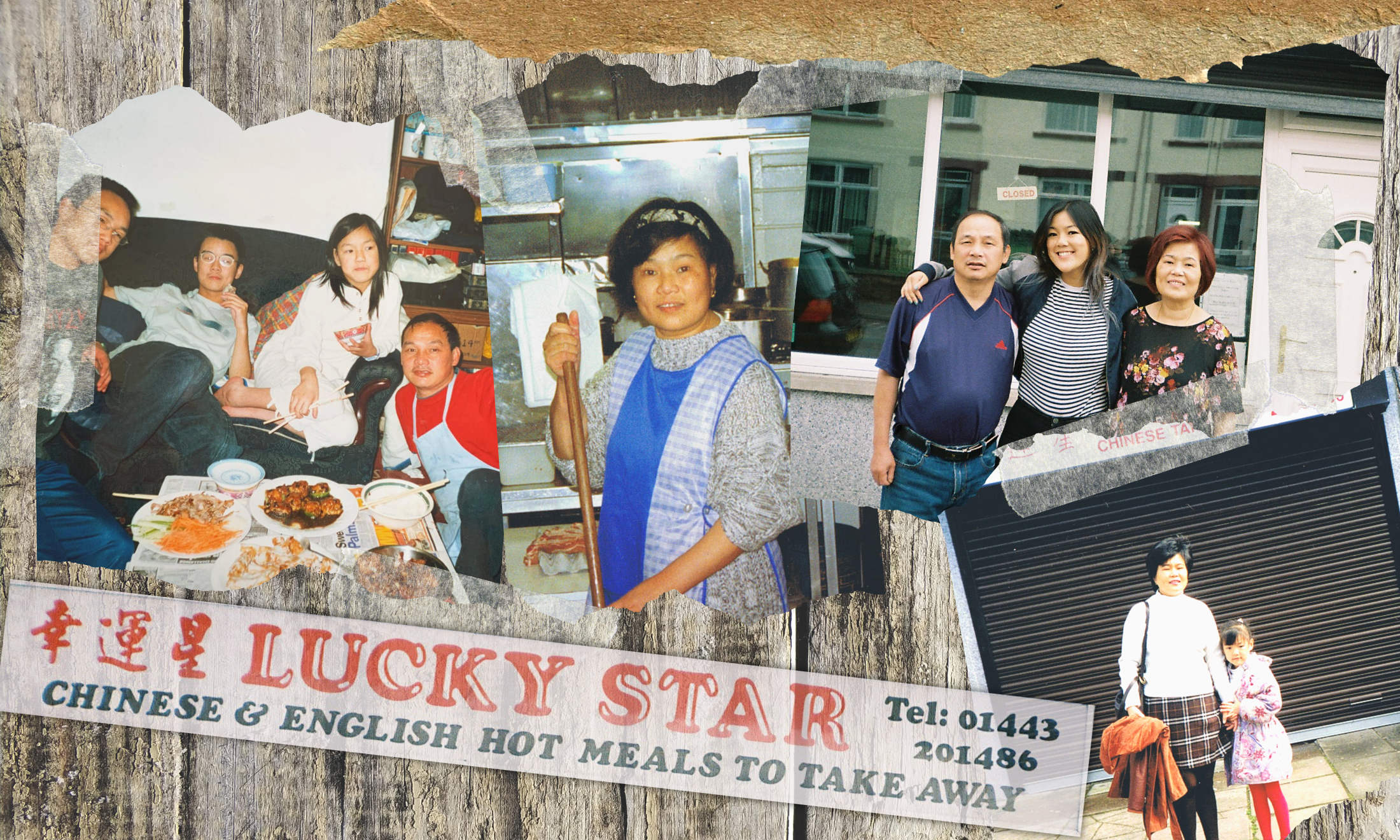

‘It was exhausting leading a double life’: my childhood growing up in a Chinese takeaway

In this edited extract from her new book, Angela Hui reflects on linguistic, cultural and generational divides growing up in her parents’ Chinese takeaway in Wales.

Angela Hui

21 Jul 2022

I want to open up to Dad and ask him for advice on what to do because someone in school is bullying me. A girl in my class threw my new shoes in the bin today. No one helped me and everyone rushed off to class because the bell had rung and I had to fish them out of the bin and now they were sticky, covered in fizzy red pop and gunk from the other kids’ leftover food. I silently sobbed in the toilets alone, trying to wash them out in the sinks and dabbing them dry with toilet paper.

Should I confront this person? Should I retaliate? Should I tell the teacher? But if I dob on them, would that make me a grass? Worse, even more unpopular than I am now? As always, whenever I try to muster enough courage to call for Dad’s attention or try to speak to him, I always chicken out and pretend everything’s fine.

My parents were supposed to be my protectors. We’re taught as children that we’re supposed to have this unbreakable, close bond, but every time I tried talking to them it was like walking through a field of landmines. Any words or actions could trigger an explosion and, more often than not, it would end in tears or frustration because of miscommunication. Because my parents’ mother tongues were Cantonese and mine was English, our conversations always relied on poor translations using a dictionary or Google, which meant nuances, slang and cultural references were often lost.

“It was exhausting leading a double life; being a different person depending on who I was with”

I was comfortable and spoke English at ease with friends and teachers at school, but this meant I bottled up my anxiety only to release it at home. It was exhausting leading a double life; being a different person depending on who I was with. I had nowhere to channel my fury and confusion, and so I took it out on my parents and blamed them for not being able to speak the same language and for not being bilingual too.

My brothers and I would gang up on them. We could converse easily because we spoke Chinglish; a mix of English and Cantonese. We gossiped about our parents behind their backs or told each other things about the shop in secret, knowing full well that they couldn’t understand us. It was a mean bullying tactic whenever we purposely spoke back in English against them. Mum could always tell when we were badmouthing her, and she often followed up our conversations with ‘I don’t understand what you’re saying. Stop speaking in English to each other. What are you saying? We’re a Chinese household, we speak in Cantonese.’

On top of an actual language barrier, my parents didn’t have the luxury to give time for ‘smaller’ issues as they were focused on the takeaway, our livelihoods and feeding the family. I wanted to talk to them about stuff that mattered, such as the bullying, my anxiety, career prospects, my identity crisis and going through puberty.

“Wealth may bring comfort and security, but time is life’s greatest asset, and we never seemed to have enough of it”

But what would my parents make of me being bullied in school, if they knew what was happening? Would they step in to help? Would they kick up a fuss? Probably not. They’d most likely tell me to stop being so overdramatic, fight back and get over it. Chinese culture is a very black and white concept where feelings of sadness and hopelessness are believed to be one’s own fault for not trying hard enough. Depression, anxiety and other mental health issues do not hold the same significance in other cultures as they do in Western societies. So, on top of trying to grapple with the linguistic and inevitable generational divide, there was also a cultural divide that meant we never saw eye to eye.

Growing up, I would have loved to learn more about them, their backstory, as I didn’t know anything about my parents’ lives before they had us. Why did they choose the South Wales Valleys to settle, of all places? What was it like selling noodles from a cart where they grew up in Hong Kong? What was growing up on a farm in China like? I rarely got the chance to ask these questions because the struggle to stay afloat and to put food on the table was more important.

Not finding the right words to say to each other resulted in a hint of loss, perhaps, or unexpected distance. Wealth may bring comfort and security, but time is life’s greatest asset, and we never seemed to have enough of it. No time for each other and no time to meaningfully be with family. Working less, though, was not an option for low-paying, self-employed businesses like ourselves.

This edited extract is taken from Takeaway by Angela Hui and is available from 21 July via Hachette.