Illustration by Mariel Richards

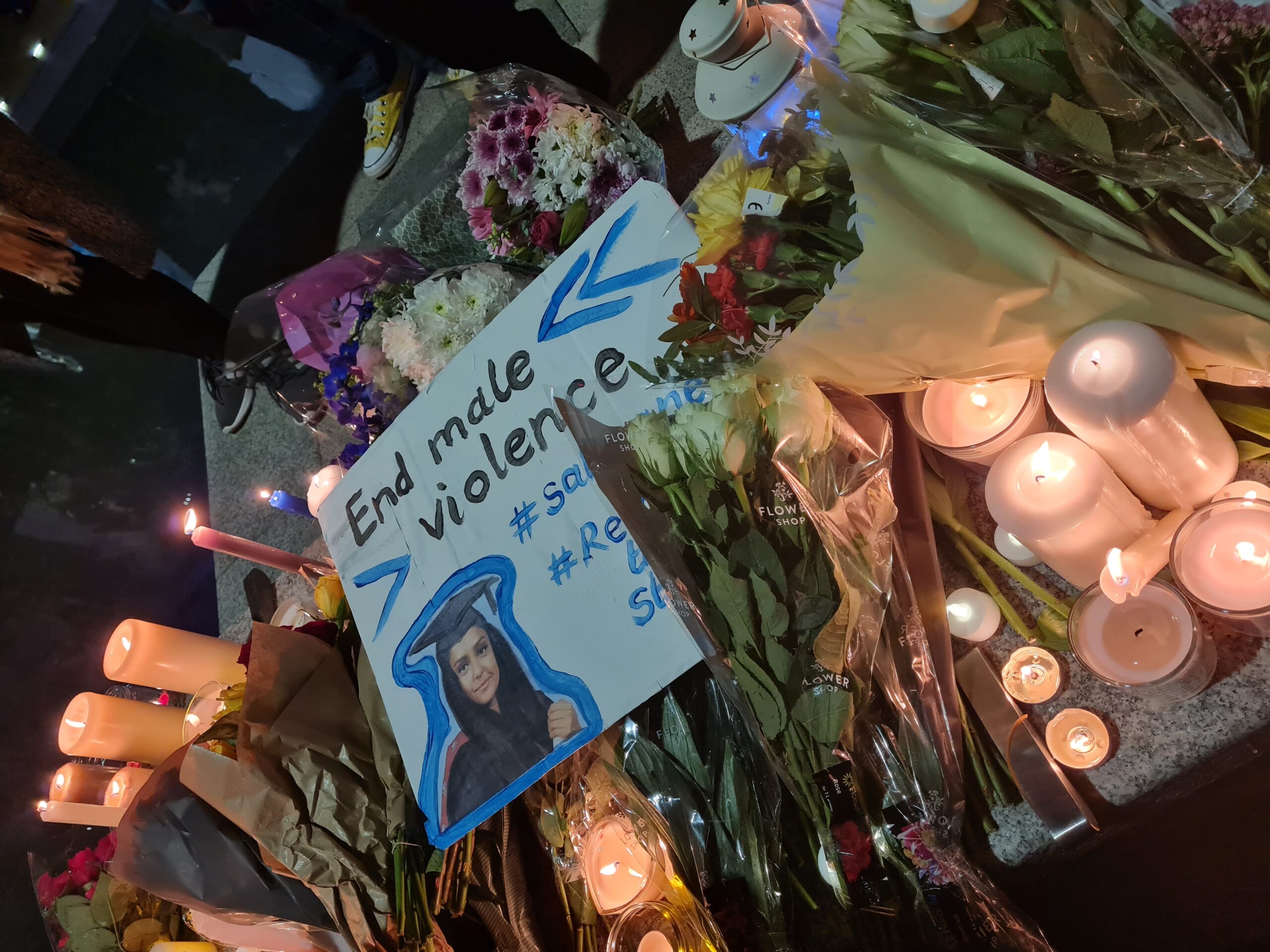

In the early 20th Century, King Edward VIII gifted his lover, Wallis Simpson, a Cartier heart charm with the inscription “The Heart Has Its Reasons”. He later went on to abdicate the throne to be with her.

Heart shaped symbols in jewellery have been popular for hundreds of years, representing everything from friendship and affection to devotion and love. It’s also a tradition amongst South Asians to gift their children gold jewellery at special occasions throughout their lives, starting right from birth.

Both concepts collided when, on my 18th birthday, my mother gave me my very own gold necklace with a heart charm. I instantly fell in love. Over the years, the chain went on to become one of the most important things that I owned – in part, because I saw it as intrinsically tied to my cultural tradition, but also because it meant so much to be given the responsibility of looking after something so expensive.

This was also the only piece of gold I owned, even though in South Asian culture, women are usually given a wealth of gold throughout their lives for adornment, but most importantly, financial security. Men in the family are the breadwinners who control the money flow, but the women always have a stash of gold, just in case. In our culture, gold is abundant – whilst it’s a symbol of status, most South Asian families nonetheless own lots of gold, even if they aren’t well off. An average South Asian family ends up spending to £20,000 to £25,000 just on wedding jewellery.

“The necklace was in many ways a symbol of the privilege I’ve had, getting everything my mother didn’t”

As a commodity, there’s a difference between the way older, first-generation immigrant Asians and younger generation British Asians view gold. While today’s generation understands the emotional value and beauty of gold, we don’t fixate over it. But first generation immigrants coming to Britain brought these traditions over and passed it along to their children – for them, preserving gold would have provided them with a sense of security in an unknown country. They would have been able to sell off the gold at any moment of crisis, so the investment was worthwhile.

After just one year, I lost my gold necklace. To make matters worse, I already have a reputation for losing things, which is why my mother waited this long to gift me something so valuable, both financially and sentimentally. Unsurprisingly, I feel horrible. Postponing telling her what happened, I’ve searched everywhere, to no avail; when we moved house, I saw the event as a good opportunity to comb through my belongings and having been through everything, I still can’t find it.

My mother’s life has been difficult and complex, and her story can in many ways be told through her relationship with gold. Orphaned at a very young age, my grandfather, who came to the UK before her, had always wished to give my mother gold as a token of his love. After he died, her adopted guardian stole all his earnings, but he did fulfil his wish by taking her to the jewellers. She was given the cheapest, smallest set possible. Today, it’s still the only gold she owns.

At 19, she was coerced into an arranged marriage. Despite the groom’s family promising to bestow her with the minimum amount of jewellery they could get away with, they failed to even provide half of what was promised, and even that was taken from her straight after the wedding. Looking back at my mother’s story told through gold, I realise that the necklace was in many ways a symbol of the privilege I’ve had, getting everything my mother didn’t.

I’m scared to tell my mum about what happened to the necklace. What if she thinks I can’t be trusted, because I lost something that meant so much to her, after everything?

“In a dark room huddled up together on a single bed every night, I was her only light in the dark”

The other day, my sister dug up her gold necklace, a simpler version of mine. “Kill me if I ever lose this,” she said, right in front of my mum. “Like seriously, kill me.” I silently threw powerful death stares at the back of her head, even though she clearly didn’t know what she’d touched on. But my mum then said, “If you guys ever lose one of these I seriously won’t be upset.” Her tone was passive, almost disinterested.

“I’ve been unhappy for most of my life – I don’t want to be sad over anything else anymore.” Perhaps she meant that after everything she’d been through, something like a necklace just isn’t worth the distress. But I also wondered whether she’d found out somehow and if this was her indirect way of telling me it was okay, and that I could come forth with my burden.

This is probably the biggest secret I’ve kept from my mum – apart from the occasional late night outing. Our mother and daughter relationship is pretty strong. From being a lone 20-year-old with a tiny baby living in a one-bedroom studio flat to working three jobs, way below minimum wage, to trying to bring her husband to London – her life has been a hard one.

But in a dark room huddled up together on a single bed every night, I was her only light in the dark. She says I was the first good thing in her life – even though she had four more children after me – I will forever be the first. It’s safe to say if she’s been through so much, she can probably handle one instance of carelessness and stupidity from her young, foolish daughter right?

People may have fought over golden nuggets for decades, and it might mean a lot in my culture. But ain’t no golden nugget sparkly enough to come between me and my mum.

From gal-dem’s third print issue, on the theme of secrets