Trigger warning: this article refers to suicide

There are certain days I feel starkly aware I’m in an emotional no-mans land. These are the days I wake up to find out Aaron Armstrong, boyfriend of ex Love Island star, Sophie Gradon, killed himself after she killed herself. Or I read about the deaths of US chef, Antony Bourdain, and the singer, Avicii. Or even when I realise it’s #NationalSuicidePreventionDay. On those days I consume social media as normal. But I can’t help but reflect on how the well-meaning news items and hashtags make me, a suicide survivor, feel.

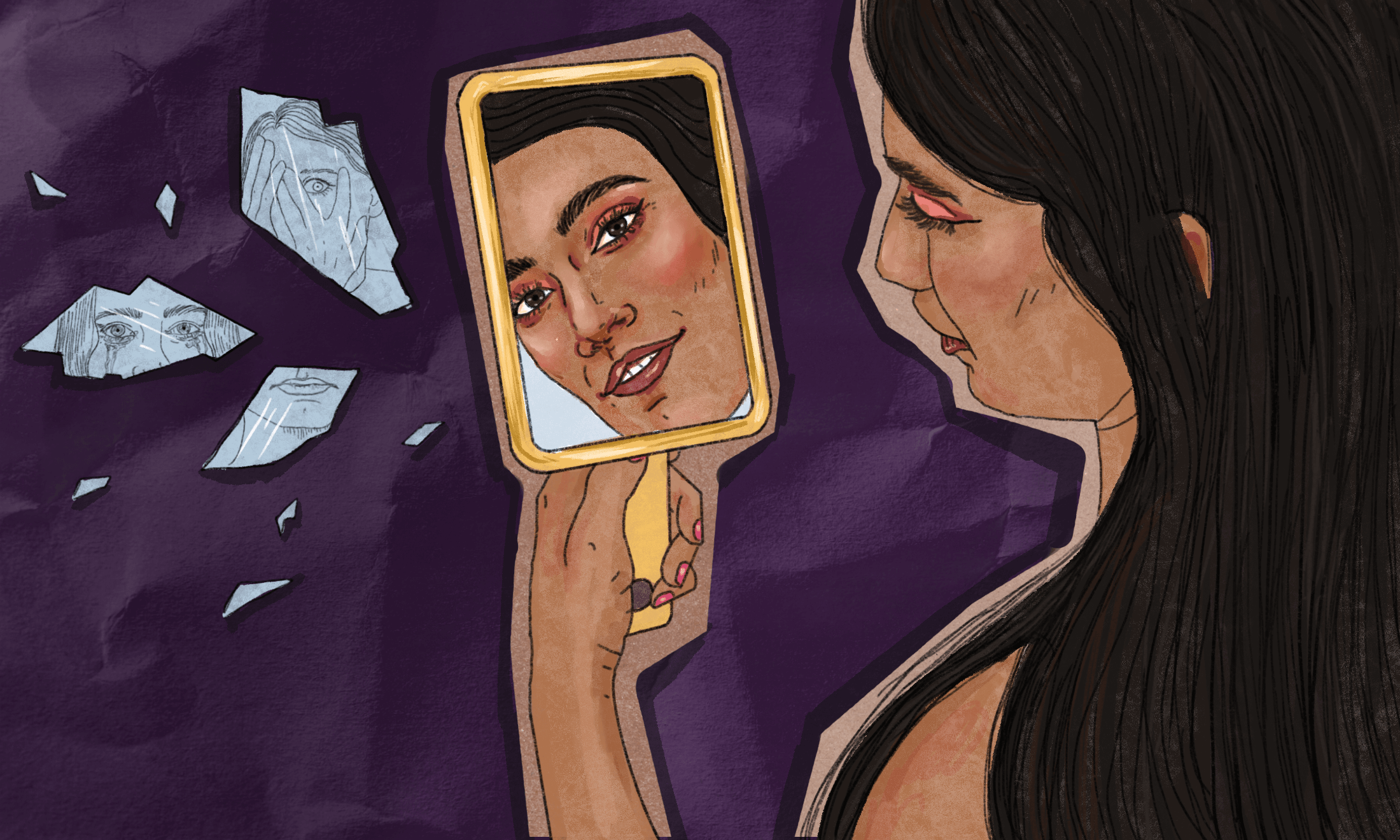

Trying to have my experiences taken seriously by my own community, as a woman from a Pakistani, Muslim background, is an uphill struggle. Journalist Poorna Bell writes beautifully about the treatment of suicide amongst Asian communities, describing it as a silent death, accompanied by grief that’s dismissed or never acknowledged because of the shame the act itself brings.

The reality is similar for those in these communities who have survived a suicide attempt, or are supporting their suicidal loved ones. It took my parents a while to come to terms with my mental health, for a while I’m sure they were convinced I just had low iron. But after accepting the reality, they supported me as best they could – something I am eternally grateful for.

The conversation around suicide desperately needs to change. As a suicide survivor, or a suicidal person, it’s really fucking hard to see the word “suicide” bandied around on social media when you’re least expecting it. And believe it or not, but most of us don’t have #NationalSuicidePreventionDay saved as a date in the diary. Some may think we’re being snowflakes, triggered by a hashtag, but for some suicide survivors, this day is a challenge. On awareness days I can feel more silenced than ever, especially as “suicide” is a word my Pakistani community has taught me to associate with shame.

“I’ve noticed that there’s a gaping chasm between the perceived understanding around suicide and how that contrasts with the tragic reality, particularly as an ethnic minority”

In our wider family when it came to my feelings, I was always just… fine. My parents never told their siblings or parents how close they came to losing a daughter, in turn making me believe that maybe this wasn’t that serious, that maybe I was fine after all. Their silence made me feel guilty for forcing them to lie to our family and ashamed I was a part of their life they could no longer mention. I found out from a cousin a few years later that many of my relatives eventually learned about my suicide attempts and hospitalisation through an article I wrote. Yet no one got in touch, or tried to see if my parents were okay. My community finds it too awkward to discuss.

It’s also a struggle to learn how to care for yourself a suicide survivor when health services aren’t always accommodating. You take yourself to A&E, but wait for hours and get sent home after a few more, because if you haven’t actually tried to end your life, you’re apparently not in any real danger. If you have tried to harm yourself, you can still wait for hours and still be sent home. In both cases, you’re lucky if it’s with new meds, or you’re on a 13-week or more wait for NHS therapy.

The provisions for those who feel suicidal can feel scarce, but we shouldn’t forgo the help that is available to us. However, blanket claims that A&E is the beginning of the healing process does a disservice to anyone who has ever felt suicidal, because the recovery process is far more complex than many may think.

I’ve noticed that there’s a gaping chasm between the perceived understanding around suicide and how that contrasts with the tragic reality, particularly as an ethnic minority. It sort of reminds me of the scene from the film 500 Days Of Summer where the screen is split in two for the protagonist: we see his painful reality play out vs his hopeful expectation. When the Mental Health Foundation in the UK reports that people from black and ethnic minority groups are more likely to be diagnosed with a mental health problem and most likely to disengage from mainstream mental health services, we really need to ask ourselves if a standard tweet or a quick reach-out online to a friend, is really enough. Our reality is always harder than you may expect.

As someone who no longer practices Islam, I know first-hand what this judgement is like: as if my lack of faith has a direct correlation with my poor mental state. The notion that you’re attention seeking is also hard to escape; South Asian women like myself are expected to be seen and not heard.

“The conversations need to recognise that being suicidal also means you’ve saved your own life more times than most people will ever have to, and champion that as a strength, not a condition that makes you a victim”

So what do we do? Well, we reach out by talking to a friend, an action that places the onus on the individual rather than society and which often results in people trying to fix a problem that they’re not equipped to deal with. A reach-out approach also ignores the systemic changes that need to take place within our healthcare system, not to mention the wider support needed to cater mental healthcare to those from BAME backgrounds. I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve been met with frustration after reaching out to a friend when they’ve realised – yep, I’m still suicidal at the end of the conversation. I’ve been told numerous times that because I’m talking about suicide, it’s proof that it can’t be that serious. People have left the conversation because they weren’t prepared for the longevity and patience required.

I’ve also noticed that the way suicide can be glamorised in the media – placing the spotlight on the rich, white and troubled – inadvertently erases the struggles of those whose intersections don’t afford them the privilege of visibility. It acts as a way of dismissing our struggles and making the suicides of ethnic minorities less tragic. Seeing Twitter tell me that I simply just need to “reach out” after the death of a much-loved celebrity hits the timeline, when my own community has programmed me to suffer in silence, fortifies a culture of complacency. Failing to consider the cultural nuances that prevent these conversation from happening in the first place can often result in feelings of further isolation.

Suicide awareness should encourage your average, non-suicidal person to prepare to make contact with a suicidal friend, so they have support when they need it most. Suicide prevention also means we should have these conversations beyond the days when a person with wealth and privilege has lost their own battle. We also need to acknowledge how much harder it is to disclose your mental state as a person of colour, as that often comes with a whole set of judgements from your community about your way of life and the idea that you’ve somehow caused your own ill health.

Useful resources on mental health and suicide:

- Mind, open Monday to Friday, 9am-6pm on 0300 123 3393

- Samaritans offers a listening service which is open 24 hours a day, on 116 123 (UK and ROI – this number is FREE to call and will not appear on your phone bill)

- The Mix is a free support service for people under 25. Call 0808 808 4994 or email: help@themix.org.uk

- Rethink Mental Illness offers practical help through its advice line which can be reached on 0300 5000 927 (open Monday to Friday 10am-4pm). More info can be found on www.rethink.org.