Photography via Canva

The dilemma of British Vogue’s cover and Black representation

Is British Vogue’s February cover a new Black subjectivity unafraid of provoking the connotations linked to dark skin? Or is Pavarotti’s skin tone modification a superficial use of exoticised elements of Blackness?

Funmi Lijadu

20 Jan 2022

British Vogue’s February 2022 issue boldly declares that this is “fashion now”, featuring an ensemble of stunning Black models across the two covers. The covers are bold and black, with the poised models facing the camera head-on, taking up space with a quiet confidence. The dark hue of their skin is near indecipherable from the space behind them. One is a group portrait depicting Adut Akech, Amar Akway, Majesty Amare, Akon Changkou, Maty Fall, Janet Jumbo, Abény Nhial, Nyagua Ruea and Anok Yai. The second is a profile of supermodel Adut Akech sitting cross-legged.

Their presence as Black, African cover stars is undoubtedly significant because centre-stage Black representation is still rare in establishment publications like Vogue. Under Shulman’s 25 years at the helm of the magazine, only two Black models were given solo covers: Naomi Campbell and Jourdan Dunn (12 years apart).

Edward Enninful, British Vogue’s first Black editor-in-chief, who was appointed in 2017, views the cover as an emblem of diversity and inclusion. In an Instagram caption, he wrote: “Every one of these brilliant models is of African descent…the rise of African representation in modelling [sic] is not only about symbolism, nor even simple beauty standards. It is about the elevation of a continent.”

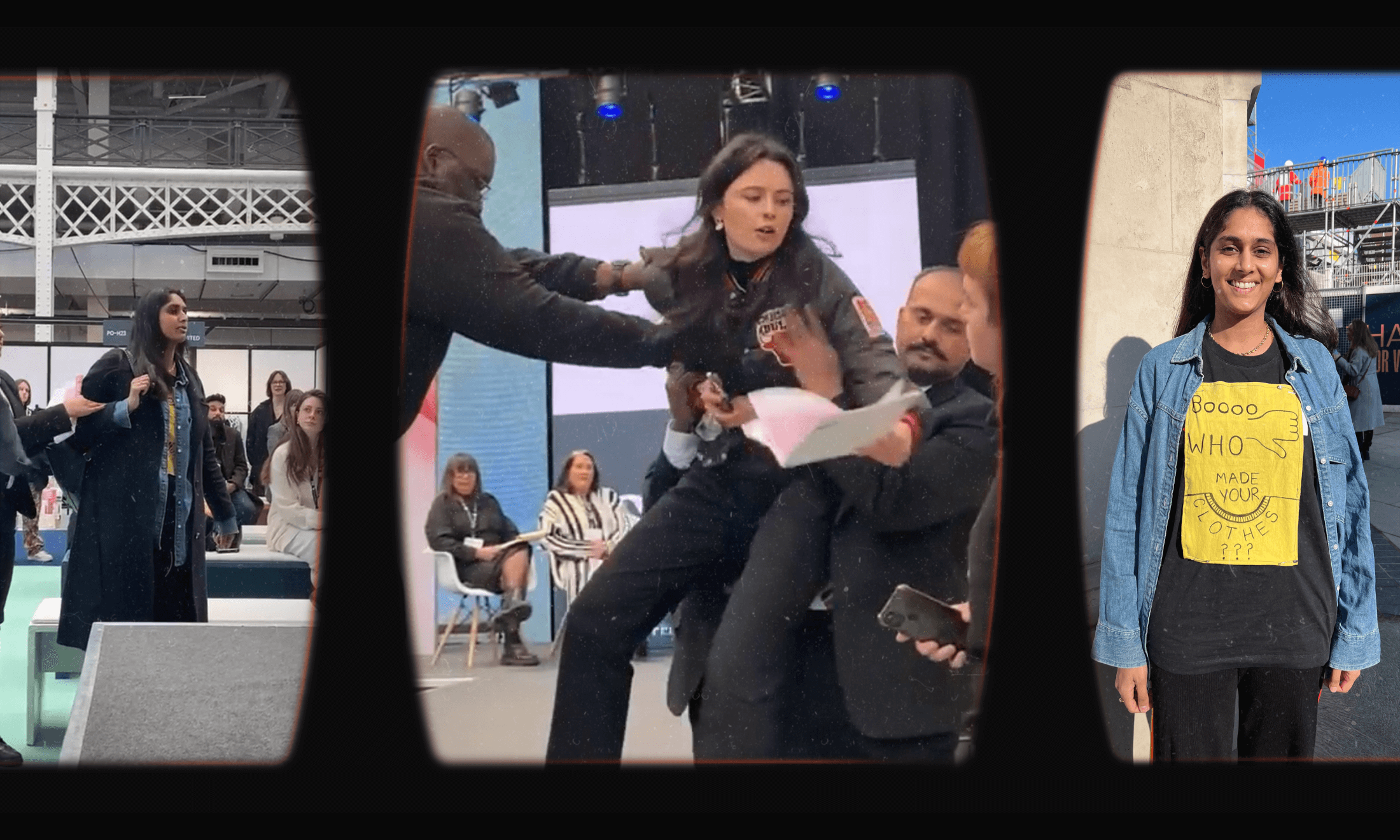

However, considerable backlash ensued online. Not from racists but from those who believe the fashion world often celebrates Blackness in terms of extremes. Many noted the fact that the models’ natural hair was covered with straight-haired wigs and that their natural complexions were significantly darkened. A particularly striking tweet suggested that the images reproduce “European colonial, fetishistic obsessions. These are objects, not persons.”

The industry does appear to favour either extremely light skin or extremely dark skin, neglecting the wide range of shades in between. I wonder if dark-skinned Black women took up more space as image-makers, whether this rigid representation would shift?

For those familiar with the editorial’s photographer, the cover’s aesthetic will come as no surprise. The cover image was shot by Rafael Pavarotti, who plays with vivid colour palettes that often intensify the darkness of his Black subjects’ skin. Pavarotti is a light-skinned Brazilian photographer who describes his work as a “celebration of Black and indigenous experience”.

“This critique aimed at the British Vogue cover is rooted in an awareness that the fetishisation of dark skin cannot reverse the impacts of anti-Blackness”

Pavarotti’s persistent motif of darkening models’ skin appears to draw on the Western notion of certain African art styles as ‘fetish’ art. His Instagram features abstract Tanzanian Makonde sculptures, particularly “shetani”, translated into English as “devil”.

If these sculptures are a big influence for Pavarotti, it suggests that his aesthetic is not a fresh statement, but a reflection of the bold motifs that Europeans come to anticipate and demand when they are viewing African art. Relentlessly depicting present-day models in a style that Europeans read as otherworldly and spiritual, inadvertently contributes to exoticisation of Black skin.

The cover features five stunning South Sudanese models. Their rise is emblematic of a global increase of dark-skinned visibility in the media. As Instagram platform @darkesthue notes, this visibility is both “empowering and evidence of exotification and commodification”. Additionally, Akau Jambo, a South-Sudanese comedian noted that though he is proud of the global rise of African models, the cover fell short: “…there is nobody moving around looking like this…this is not art. This is Black Skin Porn. Black Fetish. Reverse Bleaching”.

In fact, the skin of the models ended up darkened to a deep, glossy black in the final images. When comparing the video of the models behind the scenes to the finished cover, the contrast becomes stark.

You could argue the cover is simply surrealist genius, a new Black subjectivity unafraid of provoking the connotations linked to dark Black skin. Or is Pavarotti’s skin tone modification a superficial use of exoticised elements of Blackness transferred onto the models? Either way, his position as a male, light-skinned photographer makes his employment of extremes foregrounded by his social power.

Contextually, the deliberate darkening of skin tone across different types of media has historic connotations. Specifically, blackface involves the extreme darkening of white people’s skin as well as racial impersonation – an imitation tied up in white supremacist dehumanisation.

The visual language of blackface has existed as far back as Shakespearean theatre and is as recent as 2019 Gucci-released jumpers that resembled blackface tropes. Of course, the deliberate darkening of ethnically Black people is not equivalent to white performances of Blackness, the shoot arguably evokes dehumanising imagery, though defended as abstract.

“British Vogue’s cover illustrates a highly stylised form of Blackness, marketed to consumers as a triumphant image of progress. But it is worth asking, whose dream are we being sold?”

Contrastingly, some have defended the artistic direction of the cover, suggesting that critics simply do not understand the intention behind this kind of art. The cover has been defended as purely ‘conceptual’, made for artistic pleasure. Although models of all races are employed as mouldable artistic mediums for creative teams, Black models face a unique set of social conditions that could cause unsatisfactory representation.

In a 2017 essay, critic Noël Siqi addressed the dilemma of Black representation, writing, “black female bodies have the additional burden of bearing postcolonial and racist attitudes…In the rare cases that Black models are in fashion magazines, their appearances are either highly racialized or ‘whitewashed’”.

Evidently, the fashion industry is governed by strict European beauty standards that deems white, thin, non-disabled bodies as most worthy of being platformed. This means that when Black representation does occur, there is so much pressure for it to be done perfectly.

However, as audiences possess more autonomy in the digital age, our conversations must stretch beyond the realm of creative intention and explore the potential impacts of certain types of representation. Consumers are entitled to question and interrogate the subtle socio-cultural meanings embedded in artistic choices. This critique aimed at the British Vogue cover is rooted in an awareness that the fetishisation of dark skin cannot reverse the impacts of anti-Blackness. Black representation is not automatically liberating if deeply entrenched stereotypes can be hidden under the guise of avant-garde art.

Ultimately, it is important to peel back fashion’s layers of fantasy, to expose the shadowy power dynamics behind media representation. British Vogue’s cover illustrates a highly stylised form of Blackness, marketed to consumers as a triumphant image of progress. But it is worth asking, whose dream are we being sold?

It is important to celebrate these models at the top of their game and an industry where Black representation in fashion is moving beyond novelty into standard practice. In the meantime, I think Black audiences must defend their right to critique and question whether they identify with the images of progress they are being persuaded to buy.