via author

There are only three Jewish people left in Iraq. Where did they all go?

Uncovering the forgotten history of Iraq's lost Jewish community.

Sandy Rashty and Editors

01 Sep 2021

Welcome back to ‘Forgotten Diasporas’, gal-dem’s week-long series exploring histories of movement, survival and diasporic identity.

Content warning: mentions of death and antisemitism

“The flowers in Iraq were special. I remember their smell. Each one was brighter than the next, each with a different scent. The roses were so big. I remember swimming in the Tigris River in Baghdad. It was cold, but clean and fresh. The water almost tasted sweet. We lived in a house overlooking the river. I grew up there with my parents, siblings and a dog named Lassie. I used to call down to the sellers from the balcony, asking what fresh fish had been caught that day.

“It was a different life. It was a time when we could all play, laugh and sing together.”

These are the memories of my grandma, who was born in Baghdad to an Iraqi Jewish family in 1927. She shares her story with me over a pot of Arabic tea at her home in north-west London.

She has a proud identity, having grown up in a small but established community in Iraq that dated back more than 2,500 years. Prominent members of the community included Sir Sassoon Eskell, Iraq’s first Finance Minister who served under King Faisal I in the early 20th century; Reneé Dangoor, crowned Miss Iraq in 1947; and multiple poets and musicians including Saleh and Daud Al-Kuwaity.

Many Iraqi Jews were named after Hollywood stars like Grace Kelly and Rita Hayworth, wore Western clothes and were taught both English and French in Baghdad’s Jewish schools, including its main secondary school, Frank Iny, where my parents first met as students.

My grandma remembers the country before the modern wars, rise of extremism and the purge of its once vibrant Jewish community after the establishment of Israel in 1948.

But in 2021, the picture is very different for Jewish people in Iraq. The community, which once made up a quarter of Baghdad’s population before the Jewish State of Israel was established in 1948, now has just three members left after the death of orthopaedic doctor Dhafar Fouad Eliyahu in March this year. He was among the few who refused to leave the country.

So, how did a whole community – one of the oldest Jewish communities in the world – disappear?

A history of antisemitism

Of course, there was always underlying antisemitism – which has been called history’s oldest hatred – and it reared its head in Iraq in June 1941. During the Jewish festival of Shavuot, a mob attacked Baghdad’s Jewish community, raping and kidnapping women, raiding businesses, destroying 900 homes, killing at least 180 Jews and injuring another 1,000. As a girl hiding in their family home, my grandma remembers the two-day pogrom known as the Farhud.

But overall, life for the Jews was good, she says. “I grew up in a good Iraq. It was a place where they did not say: ‘you are a Jew’. After 1948, everything really changed.” My grandmother remembers the tide turning; the growing antisemitism after the coup against the country’s British-allied monarchy on 14 July 1958. She recalls the increased persecution of Iraq’s Jews. As attacks increased, the community fled.

In 1948, there were around 150,000 Jews in Baghdad. It is believed that by 1952, 95% of the community had left. For a short period, the Iraqi government even offered the community passage out of the country, provided they gave up their citizenship and assets.

The majority saw no future in the country of their birth and relinquished everything for a new life in Israel. Others, including Zionist youths, fled without their parents’ blessing. Among them were my grandma’s brothers, with the youngest just 12 years old..

“My father cried when we found out they left,” my grandmother recalls. “He believed we should stay in our home, our country. But they didn’t listen, they went to live on a kibbutz in Israel.”

There, they went from their home to living in a tent. One brother was bitten by a snake. Others joined the Israeli army, whilst those still young enough to study were discriminated against by the majority Ashkenazi community – European-born Jews that had fled to Israel after the Holocaust.

“The Iraqi Jewish community was scapegoated for Middle Eastern conflicts, including the 1967 Six Day War between Israel and surrounding Arab states”

Stories like this occurred across the Middle East, as persecuted Jews from established communities suddenly fled their homes in Egypt, Lebanon, Syria and beyond.

Back in Iraq, the situation worsened. After 1963, the Ba’ath Party increased the persecution of its remaining Jews. They removed their passports, cut the phone lines and prevented the community from joining private clubs, including those with swimming pools. They were not allowed to attend university or sell their property.

A mother of six, my grandma remembers showing her yellow identification card to a bank clerk, explaining that it was now yellow to mark her out as a Jew. She watched the people they once called friends take over Jewish-owned businesses.

She remembers the imprisonment of Iraqi Jews suddenly accused of being “Zionist spies”, among them my grandfather Baba Naji, who was imprisoned in 1966 and 1969.

The Iraqi Jewish community was scapegoated for Middle Eastern conflicts, including the 1967 Six Day War between Israel and surrounding Arab states.

Tensions rose further as more Jews died under torture, there were secret hangings, assassinations and neighbours started to “disappear”.

In 1970, there were around 3,000 Jews left in Iraq. By 1973, the remainder covertly fled, leaving everything behind. There were a handful of around 450 that did not leave, the majority of them elderly. Now, there are just three.

Where did the diaspora go?

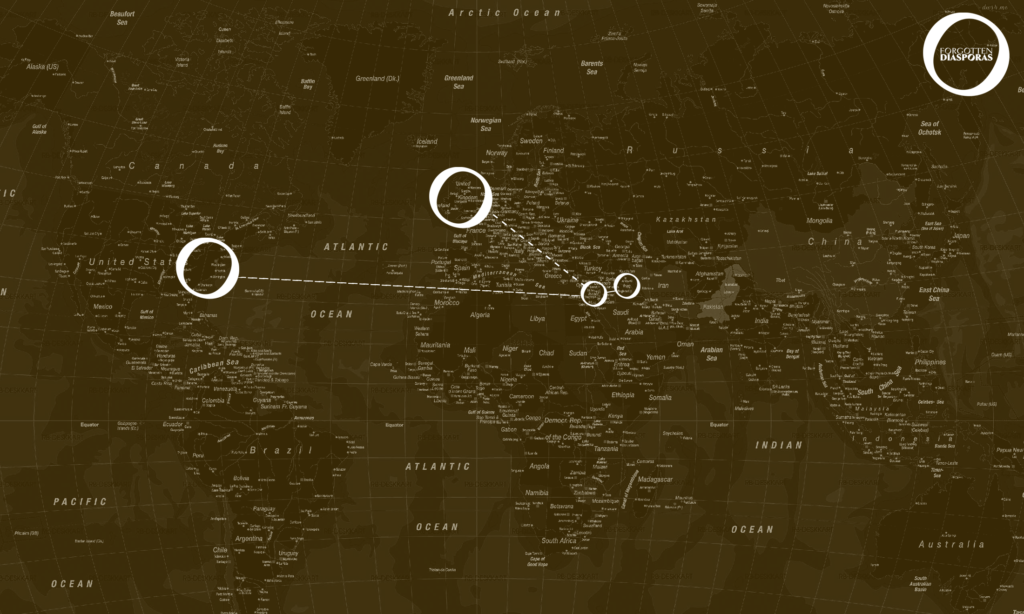

While my mother fled to Israel as a teenager with her sisters via Turkey in September 1973 (arriving a month later), my grandmother and grandfather later escaped and sought refugee status in Holland before moving to England. Meanwhile, my father’s family fled on his 15th birthday in 1971. After travelling to Iran via Kurdistan’s mountains, they too sought refuge in Holland before later moving to London.

“We wanted to leave, we didn’t care where we went,” my grandma recalls. “There were some Muslim friends who helped us at the time, they did not agree with what the government were doing.”

My mother has more anger than my grandmother. Whilst my grandmother has memories of an idyllic childhood, my mother, born in 1960, grew up under brutality, persecution and Saddam Hussein’s regime. “I was always scared,” she says. “Every time the doorbell rang, I thought they were coming to take Baba Naji. I remember visiting him in prison. I didn’t know why his skin was so pale. Now I know, he had no sunlight for all those months he was in jail. We know he slept on the floor, but we don’t know what they did to him. He would never tell us. And why was he there? He was a Jew. I still have the fear.”

“Whilst the majority of Jews who fled after 1948 moved to Israel, those who escaped in the 1960s and 1970s largely moved to Europe and the United States, the majority settling in London”

My mother also clearly remembers the 1969 public hanging of 14 people in Tahrir Square (nine Jews, three Muslims and two Christians) for allegedly spying for Israel. “I remember shaking. People in the crowd were giving out sweets and singing. I’ll never forget it,” my mum says.

Needless to say, she does not plan on ever returning to the place of her birth.

She then asks, what’s the point in reliving old memories? “We have moved on, enough,” she says, with a typically Middle Eastern wave of her hand.

Since then, Iraq’s once-thriving Jewish community has dispersed across the globe. Whilst the majority of Jews who fled after 1948 moved to Israel, those who escaped in the 1960s and 1970s largely moved to Europe and the United States, the majority settling in London. Some travelled to Canada, Australia and Singapore, whilst others stayed in Holland, where they first received refuge.

In the UK, there are several high-profile figures of Iraqi Jewish descent, including advertising brothers Lord Maurice and Charles Saatchi; TV executive Alan Yentob; former British Olympian Edward Smouha and the late Nessim Joseph Dawood, famous for his translation of the Quran for Penguin Classics, still reported to be the best-selling English version.

Preserving Iraqi Jewish history and culture

Here in London, there are Iraqi Jewish synagogues with youth clubs that have upheld the traditions and tunes that were once sung in Baghdad. In Israel, there are museums dedicated to the memory of Iraqi Jewish life. But in truth, the institutions cannot replicate the heartbeat of a community now spread across the globe.

As the London-born daughter of Baghdadi Jews, I keenly feel my hybrid identity.

I feel it as my parents alternate between Arabic (spoken in an Iraqi Jewish dialect), Hebrew and English. I feel it as a first generation child who is at home on Edgware Road, nicknamed London’s “Little Beirut”, as well as the kosher shop-filled Golders Green highstreet.

“In truth, the institutions cannot replicate the heartbeat of a community now spread across the globe”

I feel it as I sit here in my grandmother’s home, typing my family’s story. In the living room, Al Jazeera is on (as it always is). We each have a glass of slow-steamed Arabic tea, shortly followed by Turkish coffee. The coffee table is decorated with Arabian incense and a range of Middle Eastern snacks, from Medjoul dates to baklawa, fistak (pistachio nuts) and heb (sunflower seeds), traditionally cracked through our teeth. The snacks keep us going before the dinner spread of Iraqi Jewish dishes made with meat bought from the local kosher butcher.

There’s tabeet (slow cooked chicken and rice), kubba bamia (a meat and okra stew), more red rice with noodles and an array of freshly-chopped salads. If anyone is still hungry, there are always bags of pre-made aruk (chicken enclosed in rice) or patata chap (meat enclosed in potato) in the freezer. In the corner of the room, there’s a dumbuka drum and two backgammon boards. They are ready for when my great uncles return for big family gatherings in a post-Covid world.

In some ways, my family has not left Iraq behind. As my mum says: “We kept the language, the food and the music. That’s it.”

What is next for the community?

British filmmaker David Kahtan, the son of an Iraqi Jew, has spent more than 15 years documenting stories of people in the community now living across the world. “The story and the suffering of Iraq’s Jews was largely ignored by international bodies for the best part of 50 years,” he says. “Their stories are not well known. Recording these stories is now of paramount importance so that future generations will know what the Jews lived through and what they achieved.”

“Iraqi Jews and their descendants will not return to Iraq. Their future lies in Israel.” He points out that under the Kingdom of Iraq from 1932 to 1958, the Jews enjoyed constitutional rights and progressed in various fields. “They were a vital element, making major contributions to the political system, to the educational and cultural development, as well as to the economy, administration and building of the infrastructure of their nation.” He adds: “Today, there are some in Iraq who say forcing the Jews out caused great damage to Iraq’s economy.”

On this, I agree with him. My dad often questions why the international community did not do more to save Iraq’s Jews. “We should not have been forced to leave our homes,” he says. Now, despite the loss of family property, religious prayer sites and the inability to visit the place our ancestors were buried, he would not return. He sees a future for the community in Israel, especially with spikes in antisemitism across the globe.

“Now, despite the loss of family property, religious prayer sites and the inability to visit the place our ancestors were buried, he would not return”

Meanwhile, there are ongoing campaigns around the Iraqi Jewish Archive. These refer to a collection of 2,700 books, tens of thousands of documents (many taken from the Frank Iny Jewish school) and religious texts that were recovered by the United States Army from Saddam Hussein’s secret service bunker in 2003. Now being preserved in the US, they are due to be returned to Iraq.

Lyn Julis, founder of Harif, a UK charity representing Jewish people from the Middle East and North Africa, has campaigned against the Archive being returned, saying: “It belongs to Jews now living outside Iraq. It was originally stolen from Jews and for the Archive to return to Iraq, would be a travesty.”

She continues: “Iraq is the oldest of Jewish diasporas going back to the sixth century BC, in fact they call themselves Babylonian Jews. Until the Iraqi government makes amends, it is fanciful to expect any Jew would wish to go back to live in Iraq.”

Whilst my family have no desire to return to the country of their birth, there are those that think otherwise. Iraqi-born communal activist Edwin Shuker, who fled Baghdad in 1971, believes that there is still a chance for Iraq to rebuild relations with its lost Jewish community.

“The urgency of telling the stories of Iraq’s lost Jewish community, has never been stronger”

Referring to the US-brokered Abraham Accords in 2020 – which opened official relations between Israel and countries including the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Sudan and Morocco – he says: “I have no doubt there will be a reconnection. The Abraham Accords are proof. These peace accords will strengthen both the Israelis and the Arabs and prove that peace is worth more. In time the mistrust will disappear.” Mr Shuker, who has since visited Iraq and bought property in the country, adds: “For me, it’s a question of when, not if.”

The urgency of telling the stories of Iraq’s lost Jewish community, has never been stronger. Growing up amongst the largest Iraqi Jewish diaspora community, for too long I have taken for granted the availability of the stories from the survivors, and the traditions they have passed on. Since I recently got married and had our first child, the importance of preserving my heritage has dawned on me.

Like most children of Iraqi Jews, I had a Henna party – a Middle Eastern celebration filled with Arabic music, food and, of course, a belly dancer – ahead of our more traditional Jewish wedding. After the birth of our son last year, we spent days preparing ‘Shasha’, gift bags filled with popcorn, sweets and nuts (which underwent strict quality control under my grandma’s supervision) to give out to the community to celebrate the birth of our baby.

As a first generation child, I now know that unless I speak to my son in Arabic, carry on the traditions and recount the stories – they will, sadly, disappear with Iraq’s lost Jewish community.