Photography by Eman Ali

These photos explore the sensuality of Muslim women on a Kenyan island

Eman Ali's ongoing photo series follows the women of Lamu to explore their sex-positive culture and reverence for their bodies

Lubna bin Zayyad

06 May 2021

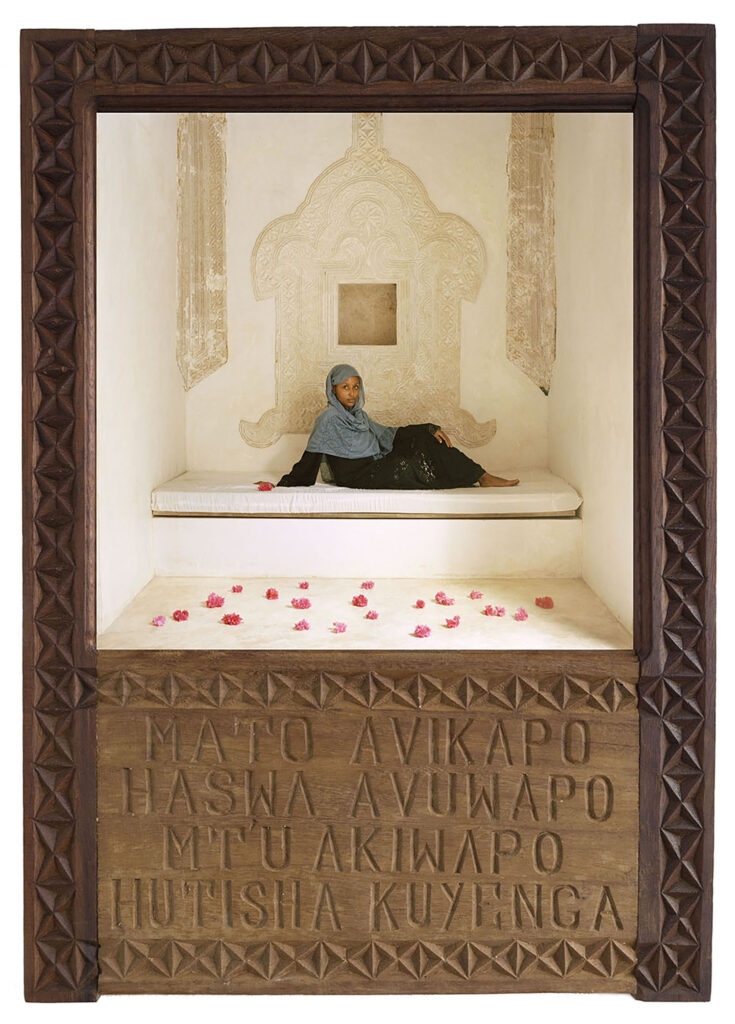

For the last two years, Omani-born London-educated photographer Eman Ali has been documenting and photographing a small group of women in Lamu, an archipelago off the coast of Kenya with a majority Muslim population. Her images examine and capture what Eman calls their “feminine energy” and the idea that the power of the feminine presence subtly permeates all aspects of Swahili island life.

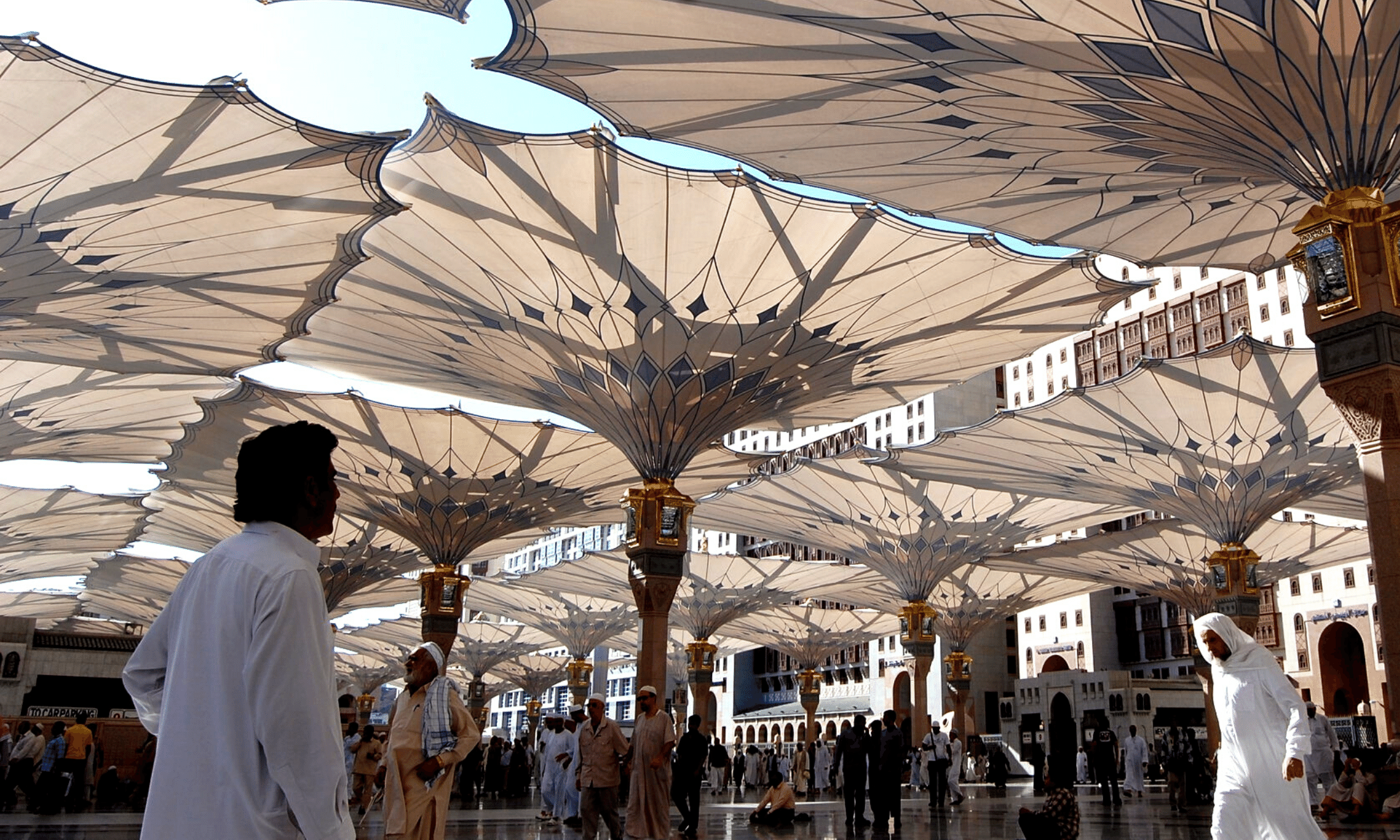

Utendi all started with a phone call from an art gallery owner in Lamu who invited Eman to explore the region and work on a project. Lamu is a historic island off the coast of Kenya that served as an important trading port for the Indian Ocean trade and the Islamic empire. Famed for its coral stone and mangrove timber architecture, Lamu’s seven centuries of history is home not only to a strong Swahili culture but also a unique fusion of Arabic, Persian and Indian traditions. This intersection between history, trade and culture has given the women of Lamu a unique view and approach to sexuality.

One photo shows beautiful folds of rich emerald fabric encasing local flowers mimicking the “natural folds of the woman’s flesh” in connection to her environment and perhaps even hinting at a more intimate erogenous zone. Another photo features a woman whose face is obscured by black fabric, the framing of the photo zooming close into the erogenous zones of her body. Her arms, her breasts, all encased in a local Swahili dress.

Everything within Swahili culture has some element of symbolism – from the local items they use to how they build homes and use their spaces. Some of this is more obvious and is expressed by the women, while some of this symbolism was revealed through Eman’s research. In one photo a woman whose hands are dyed with henna gently cups nutmeg seeds. Nutmeg is believed to be an aphrodisiac and is widely used as a natural viagra both for men and women. Fresh nutmeg, Eman tells me, is grated into warm milk and is drunk prior to having sex.

“I am really tired of this narrative and idea of what you may have of a Muslim woman.” Eman says. Muslim women’s lives have always been talked about in the media but they’re often portrayed as repressed and hidden – with very little agency given to the women themselves. But lately, books like Love, Inshallah and It’s Not About the Burqa, or Amaliah’s Lights On podcast are changing the narrative, revealing how women engage with and discuss sex, intimacy and pleasure within the context of Islam. News flash: Muslim women do have sex and actually enjoy it.

“In fact, we [Muslim women] are all very much in touch with our sexuality,” Eman explains, “but it seems in Swahili culture it is on another level. They openly discuss it and celebrate the body in a way that is remarkable and very admirable.”

“There is rhythm and there is a real understanding of how to use the body, how to take care of it, how to love it, how to appreciate it, and how to use it”

The women who were photographed by Eman made it clear that it was encouraged to openly discuss and educate one another about their bodies. She laughs when she tells me stories of the women discussing sex and natural forms of Viagra. “This is not something I could discuss with my family – let alone my mom. Yet it is very much part of their culture and they don’t shy from speaking about these things.”

When a girl gets her period there is a celebration and they talk to young girls about its importance. When a woman is married, an auntie teaches the new bride how to use her body and what sexual positions to try out. I ask Eman why this is important and she tells me that at the forefront of it all is a desire to educate women on the power of their feminine energy. “There is rhythm and there is a real understanding of how to use the body, how to take care of it, how to love it, how to appreciate it, and how to use it,” she says.

Although not conventionally viewed as inherently sexual, local architecture is something that is intertwined with the themes of the photo series, Eman says. “The house is not only a place to give birth but also to bury loved ones. It is full of life. Even the decorative designs they use all have some sort of symbol that is related to fertility or something related to the feminine.”

The further inside you go, the more private and more feminine the house becomes. Decorative elements are displayed both as an indication of wealth but also as a means to express beauty and ward off the evil eye. The home is also a metaphor for women’s bodies she tells me. “As you enter deeper it is like entering a womb.”

Eman’s works usually explore gender, religion and politics in the Middle East but this was her first foray into a new region and she welcomed the uncertainty and freedom of not knowing exactly what she wanted to do.

“[My work] comes from an autobiographical place. I am interested in exploring what is part of my life,” she tells me,“I had a loose idea, but I felt let me go there, feel it out and see where it takes me.”

Her project took her to a library where she came across the 14th-century erotic poem ‘Utendi Wa Mwana Manga (In Praise of the Arab Women)‘ by Swahili writer Fumo Liyongo. It was there that she uncovered both the name and the idea for her project.

The poem is a mixture between the world view of 14th century Swahili culture and ideology, and the consequence of Arab trade and eventual settlement. Written in Kiswahili, the poem was believed to be transcribed into Arabic 400 years later under Omani governance. ‘Utendi Wa Mwana Manga’ is a beautiful demonstration of how language and culture intersect to create a poem that is not only a steamy read (especially seven hundred years ago), but also steeped in lessons and themes about lust and the form of a woman. “The head of this noble lady/ is fair and smooth like marble/ look! its shape like a sukun,” some of it reads. A sukun is an Arabic vowel shaped like a small circle, thus the poem is praising her curves. While another is an ode to a woman’s mouth. “Her mouth gives out/ the sweet scent of the mkadi / or of the pure musk / of the civet and the wild dove.”

The poem plays an integral part of her series, Eman further intertwines it into her series by having verses etched into the wooden frames made by local artisans that encase the photographs.

Eman explores the representation and the power of the feminine presence preserved amongst these women but also deconstructs the idea people have of Muslim women and sex. The series pays homage to the connection between the women’s bodies, desire for sex, and space where these conversations and acts can take place. The most important lesson we can learn from Utendi? “[To have] a good understanding of your body and an appreciation and a celebration of what [a woman’s] body can do,” adds Eman.