‘To this day my granny swears her younger sister was taken by a mermaid’

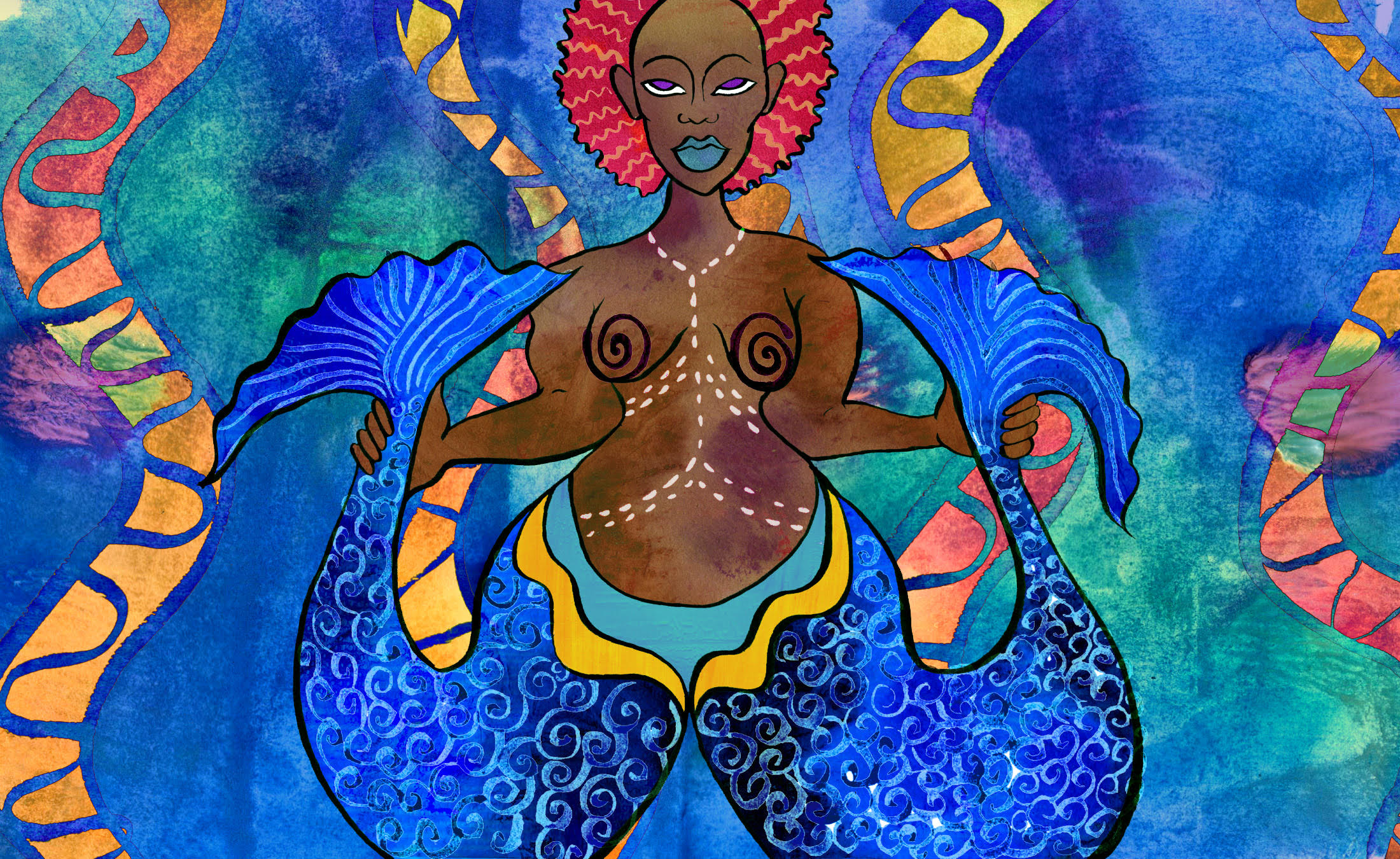

From Mami Wata, to La Siréne, mermaids have always been a part of African and Caribbean mythology and spirituality.

Zahra Spencer

09 Oct 2021

Illustration by Tessie Orange-Turner

For a long time, I only ever imagined white mermaids – specifically, a big-eyed redhead with a tiny waist, but also sometimes a generic blonde with ‘mermaid waves’ or a sultry brunette. Even though they looked nothing like me, I still saw myself in mermaids. After all, I too, grew up spending afternoons dancing in the waves, with salty seafoam in my face, under the scorching Barbados sun. I thought, even though whoever created mermaids didn’t make them for me, I knew they were still made for me.

By the time Halle Bailey (one half of the Chloe x Halle duo), was announced as the star in Disney’s new live-action remake of the Little Mermaid, I’d long discovered that mermaids were indeed Black and Brown and found in cultures all around the world. “Everybody’s folklore has mermaids, but African folklore was not being catalogued in the Americas in the way that Western mythology was, so for a long time we only knew about mermaids via that Western lens,” says Dana White, a Trinidadian-American historian, who runs a podcast dedicated to telling history from new perspectives called Musings on History.

“It just isn’t realistic to think that Hans Christian Andersen wasn’t inspired by other cultures, especially African mermaid myths,” adds Dana. “I mean look at the sea witch in the original Little Mermaid story – Ursula in the Disney movie – she’s very reminiscent of our Mami Wata or even Tiamat, who is like this amazing primordial sea goddess from ancient Babylonian mythology.”

“It just isn’t realistic to think that Hans Christian Andersen wasn’t inspired by other cultures, especially African mermaid myths”

Dana White

Afro-Caribbean folklore is rife with mermaid stories which, of course, makes sense given our proximity and relationship to the sea. In Recollections of Southern Plantation Life, author and slave owner Henry Ravenel’s comments reveal the extent to which ‘sea spirits’ have been a part of African spiritual traditions. “There was a general belief in the guardian spirits of water called cymbee among the slaves,” Ravenel wrote, “I have never been able to trace the word to any European language and conclude it must be African.”

I often think of how unfortunate it is that I grew up searching for myself in Ariel, not even considering the way my own Caribbean heritage held such rich, vibrant and mystical stories of its own. Like the legend of Mami Wata, the formidable, half-woman, half-fish water spirit, whose story managed to endure the Middle Passage and centuries of slavery – becoming a staple in Caribbean folklore. Or Haiti’s mesmerising La Siréne, who is often depicted as holding the mirror portal between the mortal and mystical realm. And of course, the sometimes beautiful, sometimes snake-like Mama Dlo, the potential lover of Papa Bois, according to Trinidadian folklore.

It wasn’t that I didn’t know of these stories growing up, but for some reason, the unshakeable image in my mind of a mermaid was one of loose waves and creamy skin. This is the insidiousness of colonialism – it makes whiteness the default. It makes you overlook what’s right in front of your eyes and will have you searching for yourself in spaces never meant for you.

“The truth is, so much of our folklore has been demonised due to its proximity to African spirituality”

Fiona Compton

“You know, the truth is, so much of our folklore has been demonised due to its proximity to African spirituality,” comments Fiona Compton, founder of Know Your Caribbean, a hugely popular platform that shares exciting snapshots of Caribbean culture and history. “We were taught to fear it and by extension, fear ourselves. And we’ve kind of perpetuated the ‘scariness’ of it. Because if you think about it, our mermaids have really been portrayed in a way that is essentially meant to ward us off the unknown dangers of the sea.”

In general, Caribbean people have a very complicated relationship with the sea. It, of course, holds a lot of generational trauma, particularly when we think of the violent way Africans were brought to the region. But at the same time, the sea is a major part of our identity as well. There is a lot that lies beneath the surface of the Caribbean Sea, and that mystery continues to move our stories along, from generation to generation.

“To this day my granny swears that her younger sister was taken by a mermaid on a day they were swimming in a river in Jacmel,” says Jadine, a 24-year-old, second-generation Haitian, living in Miami. “The story goes that her sister – my great aunt – disappeared beneath the surface, and was found a day later on a bank some ways away with memories of being dragged underneath by this woman-like figure.”

“I mean, it’s interesting because you’re tempted to brush off these stories with logic, like ‘oh, she just got pulled away by a current and washed up on the shore or something’. But then on the other hand, where there’s smoke, there must be fire, right? Like there are so many people saying the same things,” Jadine continues.

And I think, naturally, the way we relate to a lot of our folklore and stories is through fear. This creates a feeling of darkness that makes many Caribbean people wary of engaging with our folklore in a meaningful way. But it’s worthwhile to note the complex and vivid stories our ancestors were able to weave. Our mythology is as whimsical and fanciful and exciting as any other cultures around the world.

“Don’t get me wrong, yes obviously these are powerful, intimidating figures, but for me, I think there is so much in our ancestral stories that is delicate and beautiful,” says Fiona, “Look at La Sirène’s offerings. I think the things she likes are like champagne and cake and like, cigarettes or something – isn’t that beautiful? These stories have remained not because of their darkness, but because of their light. Because of the way they’ve helped us remain connected to who we are before we were slaves.”

“To this day my granny swears that her younger sister was taken by a mermaid on a day they were swimming in a river in Jacme”

Jadine

Now, in my adulthood, I am on the cusp of realising a childhood dream – watching The Little Mermaid and finally seeing myself on the screen for real. I can’t wait to experience the way that Halle Bailey is going to completely transform how the world sees that role forever. But at the same time, I’m no longer interested in squeezing and contorting myself to fit into spaces that were never designed for me. Not when there are beautifully crafted stories that weren’t only made for me, they were made from me. There is no need to rely on zombies and vampires when I have La Diablesse, Baccoo, and Soucouyant. These are mine, passed directly from my ancestors to me.

The Caribbean has always been a dreamy, whimsical, mysterious place that has enthralled and amazed for centuries. In the journey from West Africa to the region, much has been lost but at the same time, much has remained. The spread of Christianity has indelibly altered our relationship with African traditions and spirituality, but nevertheless, the links to our heritage live on in the form of mythology. Despite our colonisers’ greatest efforts, our ancestral connection to our stories has remained, largely intact and unaltered.

As Dana very aptly puts it: “Even if you aren’t a practitioner of African traditional religions, I hope we begin to see that our folklore is nothing to be ashamed of. When we lacked the sophistication to explain what was happening in the natural world, it was these stories that protected us and kept us safe. For that reason, they should be respected.”

As the Caribbean continues to redefine who we are in a post-colonial, post-independence world, reclaiming and embracing our stories will be an important aspect of that journey. Ironically, it might mean re-imagining mermaids.