Unsplash/Canva

‘The world has become bigger’: fighting for trans rights in Hong Kong

Despite its cosmopolitanism, Hong Kong society still holds conservative views on gender and sexuality. But a new generation is changing this

Jessie Lau

22 Jun 2021

This article was originally published by Open Democracy.

Ming Chan never dreamed she could live openly as a woman.

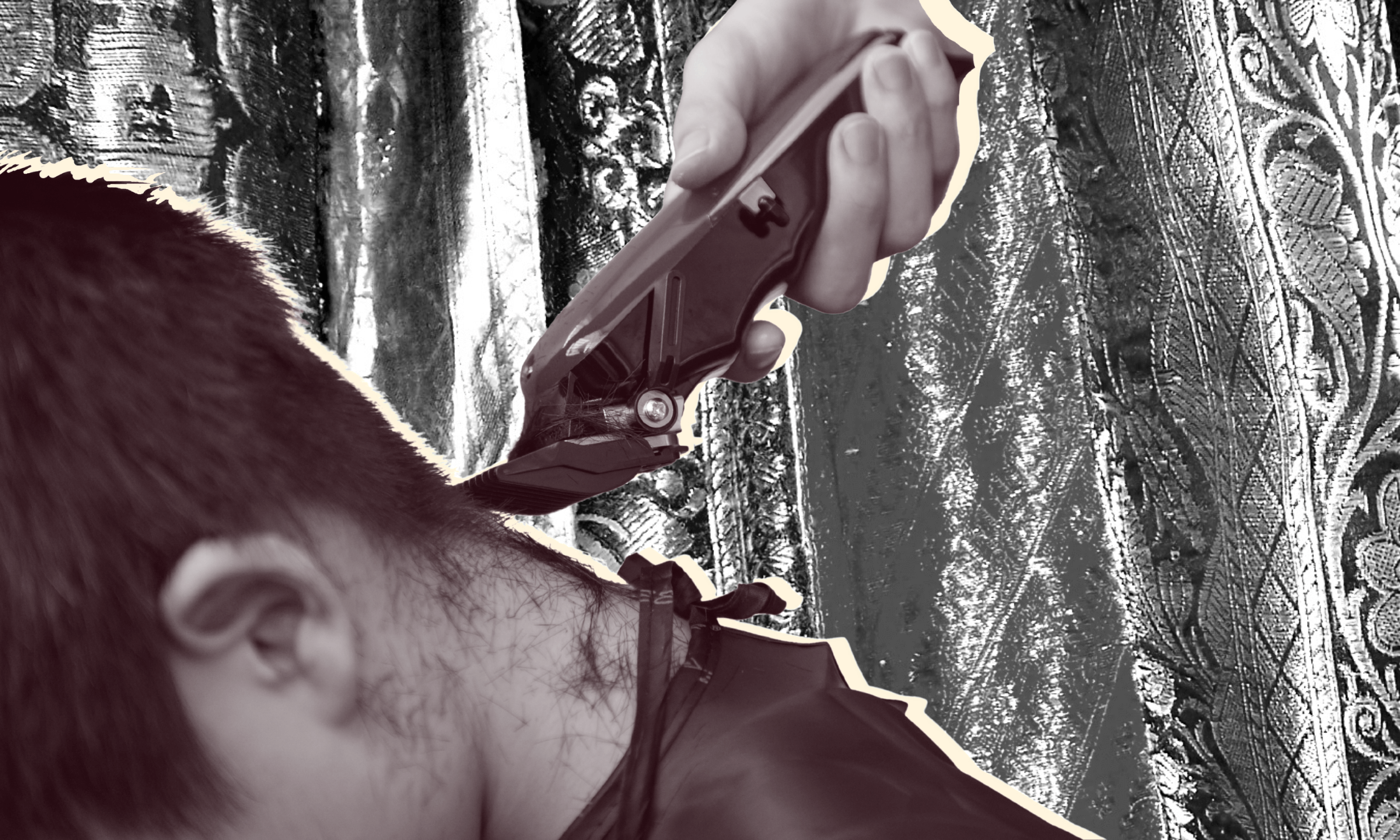

The 25-year-old transgender medical student, who was assigned male at birth, began transitioning with the use of hormone treatments four years ago.

She told openDemocracy that her journey towards living as a woman in Hong Kong has been “freeing”, and has expanded her life in ways she never thought possible.

“Now that I’ve chosen a different way to live, I’m more open to opportunities. I’m more willing to get to know people who are different. I have more freedom in expressing myself,” Chan said. “The world has become bigger.”

Although she always felt there was a mismatch between her assigned sex and gender identity, Chan had spent years resigned to life as a man.

She hid her gender identity from loved ones. She would dress up secretly in her bedroom, sharing photos online with other trans people, but she never seriously considered transitioning. “I thought this was just how my life was going to be.”

It wasn’t until her third year of university, when a psychiatrist encouraged her to consider hormone treatments, that Chan began to believe that she could live her life publicly as a woman. She also decided to come out to her family, who struggled at first with the news, but were ultimately supportive.

The psychiatrist referred her to the Gender Identity Clinic at the Prince of Wales Hospital, the only such public clinic in Hong Kong, which opened in 2016. She also took a gap year in London, to give herself space to transition before resuming her studies.

Fighting for inclusion

Chan is among a growing number of young people speaking out about gender identity and fighting for inclusion in Hong Kong, where LGBTQ+ issues remain largely taboo.

At the end of last year, she and other transgender activists founded Quarks, a trans and non-binary support group for young people navigating gender issues. In the past few months, it has built a network of more than 80 active members aged between 14 and 30, and more than 1,000 followers on social media.

In addition to offering peer support and advocating for rights, Quarks hopes to push back on Hong Kong society’s strict adherence to gender norms. Even in LGBTQ+ circles, gender fluidity remains a relatively new concept, and trans people who are homosexual or do not conform to traditional gender norms still struggle to be accepted.

“Some people think trans men or trans women should be a certain way, but we think people should just be comfortable”

“Non-binary people don’t have space to share their ideas safely or just be themselves,” said Chan. Even now, some see her as “not female enough” she said, because of her decision to not undergo sex reassignment surgery.

“A lot of people from the lesbian community still think I’m a guy,” added Chan, who identifies as a lesbian. “If we follow the old gender binary ideology, discrimination is just going to happen again. We’re trying to escape that.”

Quarks co-founder Liam Mak, a 19-year-old transgender and pansexual activist, echoed Chan’s sentiments. “Some people think trans men or trans women should be a certain way, but we think people should just be comfortable,” he said.

“Before, the trans youth community was invisible. Young people are disempowered in so many ways. We really hope to build a safe space where people can tell their stories.”

Discrimination and slow treatment

Beneath a veneer of cosmopolitanism, Hong Kong society still holds conservative views on gender and sexuality. Trans people face immense difficulties when navigating everyday life, including access to health services, and there are no legal protections against discrimination on the grounds of gender identity or sexual orientation.

In a survey released last month, the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) found that more than 50% of trans people have faced discrimination at work and in education, while more than 75% have experienced social rejection and contemplated suicide.

Many have experienced verbal abuse, physical violence and even sexual assault when attempting to use toilets that match their gender identity, according to the CUHK report, the most extensive of its kind.

If they want to legally change their gender status on identity documents, trans people must undergo full sex reassignment surgery – a requirement that activists have long fought to change, in order to make it easier to get this official gender recognition.

“In recent years, several lawsuits on gender recognition brought by trans people against the Hong Kong government have increased public awareness of these issues”

The whole process, when done through the public health system, is lengthy. Patients typically wait a year to begin mandatory psychiatric evaluations to be considered for hormone treatments. Then they must wait for physical changes to occur before further assessments to see if they are physically and psychologically fit for surgery.

It’s particularly difficult for those under the age of 18 to access hormone blockers through this system, even with parental consent. “It’s not that they can’t prescribe it, but they have to go through administrative procedures, which take a very long time,” said Robert Po Yee Loung, a local paediatrician with more than a decade of experience.

Private treatment can be quicker but very expensive. Endocrinologist appointments can cost several thousand Hong Kong dollars (HKD), while psychiatric evaluations are 1-2,000 HKD (around $125-250) per session, said private psychiatrist Gordon Wong.

Like any surgery, sex reassignment “can be dangerous, and results can be less than satisfactory,” Wong told openDemocracy. “A lot of people actually don’t want the operation, but in order to change their gender marker they’re coerced into it,” he added.

There’s no easy path ahead for Chan and others at the forefront of the city’s gender movement, yet they remain hopeful that society will one day become more inclusive.

In recent years, several lawsuits on gender recognition brought by trans people against the Hong Kong government – as well as the release of Hong Kong films depicting LGBTQ+ characters, such as ‘Tracey’ (2018) with a transgender protagonist – have increased public awareness of these issues.

Attitudes are changing, albeit slowly. A CUHK poll last year found that 60% of 1,058 respondents agree there should be laws against discrimination based on sexual orientation, up from the 56% recorded in 2016.

Next year, Hong Kong is set to be the first Asian city to host the global Gay Games. The event is already controversial, with a pro-Beijing lawmaker last week calling the games “disgraceful” and their revenue “dirty money”. Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam responded by saying such comments incite hatred and that the city will support the event and advance acceptance of sexual minorities.

Now in her last year of medical studies, Chan hopes to become a psychiatrist, so that she can help others struggling with their gender identity.

“Transgender youth represent many possibilities and are challenging the ideology of our rigid gender system. This provides hope for the community,” Chan said. “The hardware is moving very slowly – but people are trying to find a new way out.”

Tragedies like the Knowsley riot and Brianna Ghey’s murder show scapegoating minorities is a deadly game

Finland has passed life-changing laws for trans people. Why can’t England?

‘The day Ghana’s anti-LGBTQI+ bill is passed, I will be in jail’